Chartered in 1600 by Queen Elizabeth I as the “Governor and Company of Merchant of London trading into the East Indies,” the British East India Company at its 18th century peak accounted for fully half of the world’s trade—a staggering percentage then and now. In 1757, the British government ceded administrative responsibility for the Crown Jewel of its Empire, India, to the East India Company. This meant that the EIC had the full powers of a sovereign nation. It could mint money, enact and enforce laws, raise armies, and wage war—all without the consent of the Crown.

The Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or Dutch East India Company, was the world’s first megacorporation, an amalgam of several rival companies, chartered in 1602. When it issued bonds and shares of stock in the early decades of its existence, the VOC became the world’s first formally listed public company. Nominally a trading concern, the VOC was a proto-conglomerate, with interests in international trade, shipbuilding, and the production and sale of spices from the East Indies, coffee from Indonesia, sugarcane from Formosa, and wine from South Africa. The company was more of a company-state than a for-profit corporation, and in its foreign colonies had the power to wage war, arrest convicts, and even perform executions.

The VOC went bust in 1800, the EIC 74 years later. And as rich and powerful as corporations have become in the ensuing century and a half, not even Standard Oil or U.S. Steel could boast that kind of corporate might. It’s been many decades since we had to reckon with the concept of company as nation-state. But that time, alas, has come again.

Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook may not hold dominion over millions of hectares of land, but, as Adrienne LaFrance convincingly argues in the Atlantic, it has the other three elements compulsory to statehood: “currency, a philosophy of governance, and people.” Almost three billion people, astonishingly—which, as she points out, is more than the population of China and India combined.

Zuckerberg’s online empire has accomplished doing “the work of a state” masterfully. “Facebook is not merely a website, or a platform, or a publisher, or a social network, or an online directory, or a corporation, or a utility,” LaFrance writes. “It is all of these things. But Facebook is also, effectively, a hostile foreign power.”

Given that Facebook would not exist in its current form without seed money from an actual hostile foreign power, one could argue that it is a hostile foreign power installed by another hostile foreign power—like when the Soviets helped Fidel Castro take over Cuba, only instead of a smelly Marxist with a beard on a mobbed-up island off the coast of Florida, they installed malware into our actual brains.

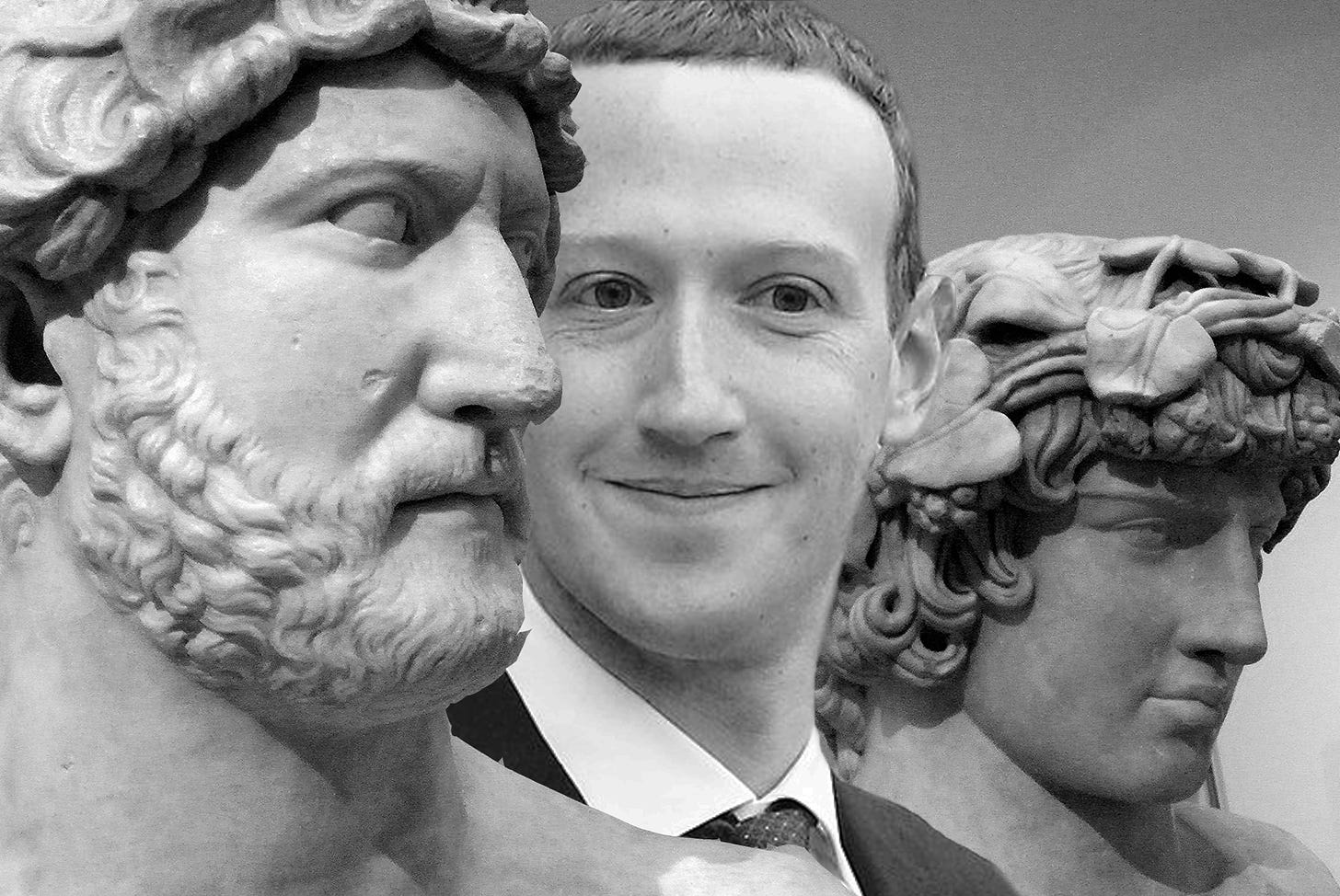

That Facebook is a tool of autocracy is not surprising, when we consider that the company is run by an autocratic tool—a megalomaniac who fancies himself a Roman emperor of old. And, O! The worlds he has conquered! The platform that began life as a lark—an app for incels to rate the pulchritude of Harvard coeds—has become, in LaFrance’s chef’s-kiss phrase, “a lie-disseminating instrument of civilizational collapse:”

Facebook executives have tolerated the promotion on their platform of propaganda, terrorist recruitment, and genocide. They point to democratic virtues like free speech to defend themselves, while dismantling democracy itself.

These hypocrisies are by now as well established as Zuckerberg’s reputation for ruthlessness. Facebook has conducted psychological experiments on its users without their consent. It built a secret tiered system to exempt its most famous users from certain content-moderation rules and suppressed internal research into Instagram’s devastating effects on teenage mental health. It has tracked individuals across the web, creating shadow profiles of people who have never registered for Facebook so it can trace their contacts. It swears to fight disinformation and misinformation, while misleading researchers who study these phenomena and diluting the reach of quality news on its platforms.

This week, Facebook is once again in the crosshairs of both Congress and the mainstream media, which continues to break devastating stories about the company and the would-be Gordian III who runs it. Maybe this time, the pressure will be enough to send Zuck to the Tom-From-MySpace pasture.

In Imperial Rome, when the generals lost faith in an emperor—which happened with Spinal-Tap-drummer-like frequency during the fourth century’s Age of Chaos—the Praetorian Guard would dispatch him. The civilization-collapsing problems of Facebook will not all be solved by the removal of the sociopath on its throne, of course, but the Board of Directors metaphorically tossing Mark Zuckerberg’s metaphorical corpse into the metaphorical Tiber would be a good start. Then, they can pick a CEO who is less Caligula and more Antoninus Pius.

That would give the rest of us—users, lawmakers, enforcement agents, victims of Facebook’s psychological experimentation—more time to figure out how to navigate the brave new world of tech companies as EIC and VOC 2.0.

Image by the author, based on this photo of A. Pius and Antinous.

A week or so ago, I looked at a credit card bill and I realized that I had authorized an annual subscription to Greg in the amount of $150. I was wondering if it was worth it.

This one piece of yours, Greg, is worth the entire subscription, and then some. With the emphasis on “and then some.”

Greg is my brother from another mother who does a job that is so vital, the job of investigating, and bringing light to, nefarious aspects of society. We are like team players who have different assignments, all in the support of humanity’s evolution to a higher and better place.

I have been keeping this next quote in my email InBasket, from summer 2020, because until this work of yours, Greg, it was the best thing I had on the subject of the horror show that is Facebook.

I report it here because it was the seed, for me, that has sprouted into this work of yours.

Facebook quote from 2020:

The hellscape that is Facebook is the most meaningful tool of political manipulation ever devised in the history of all mankind.

Rick Wilson of The Lincoln Project

https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/07/rick-wilson-on-how-the-lincoln-project-gets-in-trumps-head.html

When I read your posts I realize how little I know about everything. 😱