Igor Sechin: Russia's Darth Vader

The second most powerful man in Russia doesn't like the spotlight.

ON APRIL 9, 2021, Russian authorities raided the Moscow apartment of investigative journalist Roman Anin. “They took everything,” he told reporters later that night. “They took all the memory sticks, all the computers, including those that weren’t mine. They took telephones that didn’t belong to me. They took documents.”

Anin, who is 34, has been a thorn in the side of Putin’s inner circle since the Russian daily Novaya Gazeta moved him off the sports desk in 2006. In his career, he has exposed Sochi Games corruption, a fishy telecom deal between a Swedish company and the daughter of the Uzbek president, and the lavish excesses of the ex-husband of one of Putin’s daughters. He is the founder of iStories, a crack publication specializing in anti-corruption stories, and was one of the investigative journalists working on the Panama Papers.

So why did the authorities seize his shit now? To retaliate for a piece he wrote in 2016 for Novaya Gazeta: “The Secret of Princess Olga,” an exposé of the Robin Leech-worthy lifestyle of Olga Rozhkova, then Olga Sechina, the second wife of the second most powerful individual in the Russian Federation: Igor Sechin.

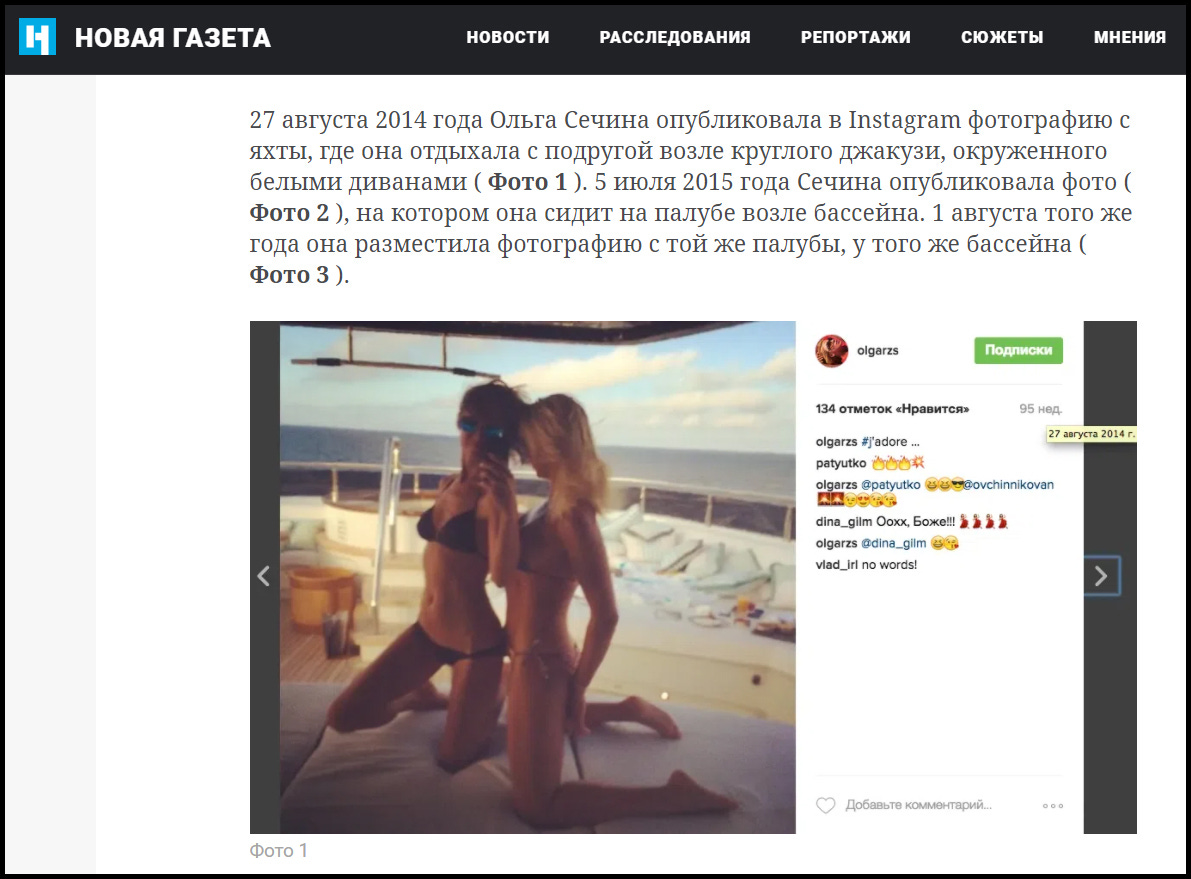

I say “exposé,” but as investigative stories go, this one didn’t require Hardy Boys-level detective work. All Anin did was screenshot numerous Instagram photos of Rozhkova cavorting half-dressed, aboard a luxurious yacht neither she nor her husband could possibly afford—photos she shared, on her own Instagram page.

Igor Sechin divorced Olga a year later—the tale of this porcine man and his younger, hotter second wife was never to be confused with Romeo and Juliet; Olga is eight full years younger than his daughter Inga—but he could not quit Roman Anin. So he leveraged his not-inconsiderable power to, um, make the reporter go through some things. As the Novaya Gazeta editorial board wrote: “Everything that is happening right now with Roman Anin is revenge.”

Here’s the thing: Anin wrote about Putin’s family and survived. Why did this piece cause him such trouble? Who the fuck is Igor Sechin, and why is he the third rail?

Vladimir Putin has spent the last 20 years consolidating power like Ivan the Terrible, terrorizing the Russian people like Stalin, and looting and pillaging like no one in the annals of Muscovy. The sickly son of impoverished parents has made himself the wealthiest individual in the world—if not in all of history. And he acquired his wealth through larceny, on an audacious scale. What does Hans Gruber say in Die Hard? “I am not a common thief; I am an exceptional thief.” Even the tsars didn’t steal as much from their own people as this Chekist twerp.

His most trusted aide-de-camp during this two-decade ruble heist is Igor Sechin. Like Putin—and, indeed, like virtually every mobster—Sechin grew up dirt poor, and was determined to do whatever it took to make it big. He was tapped to be Putin’s chief of staff back when Putin was the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg. The two have worked hand in glove ever since. When Putin ran Yeltsin’s powerful if unglamorous property management department, Sechin was his deputy. When Putin was made prime minister, Sechin was the head of secretariat. And when Putin became president, Sechin was deputy chief of the administration and then deputy prime minister, a job he held until 2012—when Putin re-assumed the position of president of Russia, and Sechin became president of Rosneft, the Russian state-owned oil company. Good work if you can get it.

In Russian political circles, Sechin is known as “Darth Vader.” They call him that because he’s particularly ruthless, notably venal, and kind of a dick. While colorful and provocative, this nickname misses the point. The Star Wars villain, father of Luke and Leia, was supremely talented in his own right. Through years of disciplined training, he harnessed the Force. Igor Sechin has no such mystical powers. He’s a crony and a thug. True, he is a linguist by training, fluent in both French and Portuguese, and thus more refined that your average brute. But in practice, this just means he can say “Give me my fucking money” in three different languages. A goon who enjoys jazz is still a goon.

If Putin is Vito Corleone, Igor Sechin is Luca Brasi. If Putin is Victor Frankenstein, Igor Sechin is, well, Igor. And if Putin is Rudy Giuliani, Igor Sechin is Bernie Kerik. That might be his closest American analog (although Sechin is much smarter, more talented, and infinitely more ruthless than the former NYC Chief of Police). Imagine if Giuliani ran the U.S. like a dictatorship for 20 years, lying and stealing and killing, and Kerik was his eternally loyal #2. Lummox, lug, lackey: that’s Igor Sechin.

Here’s a clip of him (at left in the screenshot) carrying Putin’s bags through the airport in 1996:

One could be forgiven for believing Sechin was a legitimate businessman, and not a glorified thug. He was chair of Rosneft’s board of directors even when he worked in government, and he has headed that enormous company for almost ten years. From the outside, that seems like a perfectly respectable job. I mean, it’s a “real” company, and he is its boss. Certainly Sechin’s unsavory background doing KGB work in Africa didn’t stop Rex Tillerson from making nice-nice with him, back when Trump’s first Secretary of State was running Exxon.

But beneath this respectable if oily veneer is something much darker. Sechin has done things even robber barons would think twice about. Russians regard him with terror—and with good reason. Put it this way: he is not the head of Rosneft because of his skill as a businessman. He is the head of Rosneft because he is fiercely loyal, because he shares Putin’s insatiable lust for money and power, and because he’s not afraid to bust some skulls if skulls need busting.

For starters, look at how Rosneft became the country’s largest oil company. In an excellent piece for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Todd Prince and Mike Eckel explain:

In July 2004, Sechin joined the board of Rosneft, then a relatively small firm producing just 20 million tons (140 million barrels) of oil a year. Today, the company produces more than 10 times that amount, making it the second-largest oil producer in the world after Saudi Aramco.

That enormous growth is due mainly to its acquisition – theft, some experts say – of major oil assets, like Yukos.

During that period, the Putin government undertook one of the most consequential moves of Putin's presidency: the prosecution of Yukos founder Mikhail Khodorkovsky, then Russia’s wealthiest man.

In October 2003, months after alleging corruption at Rosneft, Khodorkovsky was arrested at gunpoint at a Siberian airport on charges of fraud and tax evasion.

The government moved to nationalize Yukos, and the company's best assets were ultimately acquired by Rosneft.

In a 2005 interview with Vedomosti, Khodorkovsky called Sechin the “organizer and motor” of the Yukos case.

Sechin denies this, of course, but, I mean, have you read about what happened to Khodorkovsky? Once the wealthiest of the new oligarchs, he was kept in a cage during his show trial. This had all the hallmarks of a corrupt government trying to justify a brazen and unlawful seizure of assets. It would be like if Trump tapped Louis DeJoy to run Etsy, and then had the government arrest Jeff Bezos, seize all of Amazon, and sell it to Etsy for a song. Those are mob tactics: if not in the same genus as horse-head-in-the-bed, certainly the same family.

We could write this off as a one-shot deal, an outcome that could only have happened in the Wild West-like Moscow at that time. Except that it happened again. More than once. First, with another oil company called, confusingly, Russneft:

Rosneft [in 2005] offered Russneft to swap its 50 percent share in the Yukos unit for a stake in a subsidiary, according to media reports. Russneft’s owner, Mikhail Gutseriyev, said the deal was unfavorable and rejected it.

A year later, investigators showed up at Gutseriyev’s office amid a tax probe that threatened seizure of the company's shares.

The tycoon fled the country in 2007 to escape prosecution and Rosneft filed a lawsuit the following year seeking $200 million in damages from Russneft.

Vedomosti reported that Gutseriyev was told that Sechin was behind the tax probe, but could not reach the powerful Kremlin official to discuss the situation.

Then Sechin did the same thing with a Siberian company called Bashneft, which was controlled by an umbrella company called Sistema:

In 2014…the Russian government nationalized Bashneft. In September of that year, Sistema’s owner, Vladimir Yevtushenkov, was placed under house arrest. He was released in December 2014.

Rosneft not only ended up buying a 50 percent stake in Bashneft, but it later sued Sistema for $4.5 billion, eventually agreeing to a $1.7 billion settlement in 2017.

A year before Bashneft’s seizure, Vladimir Milov, who had been a deputy energy minister early in Putin’s first term in office, warned that Sechin had been seeking to acquire the company for a decade.

“Bashneft is the most obvious and easiest target for Sechin,” Milov predicted in 2013.

The Bashneft deal was opposed by Russia’s Economic Development Minister, the reform-minded Alexei Ulyukayev. So Sechin had him taken care of, too, as Alec Luhn of Vox relates:

Late on the night of November 14 [2016], Igor Sechin, the CEO of the Russian state oil giant Rosneft, reportedly summoned Economic Development Minister Alexei Ulyukayev to a meeting at the company’s headquarters in a czarist-era building across the river from the Kremlin.

When he arrived, Ulyukayev was handed a large amount of cash in front of Sechin — and then arrested on the spot and charged with soliciting a $2 million bribe. Ulyukayev, who insists that he is innocent, was fired by Russian President Vladimir Putin the day after his arrest….

Russian newspapers reported that Rosneft's head of security — who remains a high-ranking FSB security service official — organized the sting, presumably on Sechin’s orders.

Sechin has been charitably described as a “corporate raider,” but he’s no Carl Icahn. When Icahn executes a hostile takeover, he doesn’t put the vanquished CEOs in the hoosegow. What he’s done is more like the class bully stealing the other kids’ lunch money, albeit on a much larger scale.

As the reporter Mikhail Zygar writes in his book All the Kremlin’s Men, this is Sechin’s devious modus operandi: “Business leaders who have dealt with Sechin say he has one particular idiosyncrasy: he immediately manages to get criminal proceedings started against any potential partner as a backup, as well as to facilitate the negotiating process.”

That’s not business. That’s gangster shit.

If this is stolen lunch money, there’s an absolute fuck-ton of it. Igor built a $60 million mansion outside of Moscow, near the Presidential Palace—nice digs. And he has an ex-wife, Martina Sechina, who is somehow worth upwards of $70 million, despite showing no income for years.

As Roman Shleynov, a contributor to Anin’s iStories, explains in a piece for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP):

After Sechin and his wife divorced in 2011, she might have concluded that his name was more help than hindrance because she did not take back her maiden name, sticking with “Sechina” instead. Like Coke, Kalashnikov, or other well-known brand names, it could be the most valuable asset in her rapidly growing business empire.

And yet, there’s a problem. For years, as a public servant, her ex-husband was required to disclose his and his wife’s incomes. Until 2011, Sechin reported zero income for his wife in his annual declarations (and no extravagant amounts for himself).

But after their divorce, Sechina started acquiring stakes in telecom, electricity, agriculture, and real estate companies in Russia. Though her name had never been associated with any major companies or other sources of income that would point to any large wealth, in 2013 alone she acquired stakes in a number of Russian companies that showed assets worth over €55 million (US$ 76.7 million) on their balance sheets by the end of that year.

That’s a lot of bread to have fall in your lap suddenly—for Martina or for Igor. Schleynov continues:

It’s possible that she received a settlement from her husband after their divorce— but reporters found no large properties or other major assets in her possession in 2012 that would explain her ability to make significant real estate investments.

Her husband’s declared income in the years prior to her divorce was also not very large.

This has all the hallmarks of a corrupt official—Putin’s right-hand man, no less—boosting vast sums from the treasury, and getting caught with his hand in the proverbial cookie jar. But when this happens to Sechin, he comes for the guy who narced on him—and then, for good measure, the guy who baked the cookies.

And it’s not like all of this bad behavior can be excused by Sechin being a savvy corporate executive. He’s not there for his keen business acumen. As a thug, he’s elite. As a politician, he’s shrewd. As a CEO? That’s another story.

I mean, how hard can it be to run a state-owned oil company in Russia? There’s no shortage of crude. Competitors wind up in prison with their assets seized, as we’ve seen. Critics are sued, harassed, detained, have their comms confiscated. There are tankerfuls of money sloshing around. There are opulent mansions and island-hopping yachts and yoga-bodied blondes in bikinis. All Sechin has to do, basically, is know when to ramp up production and when to slow it down. Which decision OPEC can help him with.

Even so, Sechin’s record running Rosneft is nothing to write home about. “Sechin has clashed with just about every major figure in the Russian oil and gas sector over the years and many top officials overseeing major economic decisions,” write Prince and Eckel. “But as the head of the state's premier oil company, he’s carried out projects that often are driven not by shareholder interests—Rosneft has lost billions in value during this time—but by apparent political demands, such as the doomed investments in Venezuela.”

Venezuela happened when everyone told him, “No, Igor! Don’t dump money into that!” and he did it anyway and lost bigly, as that corrupt country’s economy teetered into hyperinflation. True, there were political considerations for Russia doing business there, which have nothing to do with money. Even so, it was a huge loss to the bottom line.

Sechin also misread the market last year, at the beginning of the global pandemic. The OPEC members knew to slow down production, anticipating a decrease in demand because of the quarantine. He convinced Putin to zig while the rest of the world zagged, and it cost him. At one point last March, a barrel of oil was selling for less than zero, at least on paper. Rosneft lost so much dough, it had to tap into the Russian “rainy-day fund” to not collapse.

Before that, there was Rosneft’s 2013 purchase of TNK-BP, the nation’s third-largest oil company. Sechin’s company paid out precisely $27,778,900,132.16—in actual U.S. dollars, not rubles—to the four Russian oligarchs who owned half of TNK-BP: Mikhail Fridman, Viktor Vekselberg, Len Blavatnik, and German Khan. (Because TNK-BP was half owned by a foreign oil company, it was more expedient to pay off the Russian billionaires than to arrest them). Almost as soon as the sale was complete, the price of oil plummeted. As Nathan Vardi of Forbes wrote in 2015, “Sechin and Putin’s mega-energy merger may have seemed like a ‘good’ strategic deal for Russia, but for Fridman, Vekselberg, Blavatnik and Khan, whose combined net worth now hovers around $55 billion, cashing out of Russia's most oil-dependent company in the spring of 2013, with West Texas Crude selling at $92 per barrel and Western banks pumping loans into Russia, may go down as the most brilliantly timed profit-taking of the decade.”

So: not a deal you want to be on the wrong side of. Herschel-Walker-to-the-Vikings bad.

And then there was the blown deal in the Arctic. The one involving Sechin’s bestie: former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. In 2012, Rosneft, entered into a $500 billion joint venture with ExxonMobil, which at the time was run by Tillerson; it was this mammoth joint venture, apparently, that inspired Putin to award Tillerson the Medal of Friendship in 2013 (at Sechin’s suggestion). The oil reserves in the Arctic, the reason for the venture, are estimated to contain 85 billion barrels. At a conservative price of $50 a barrel, that amounts to a staggering $4.25 trillion in potential gross revenue.

But the deal was scuttled. Putin invaded Ukraine and occupied the Crimea, the U.S. put him and Sechin on the sanctions list, and that was that. The Rosneft deal written about in the intelligence reports by Christopher Steele, in which the company sold off 19.5% of its ownership stake, was done to raise money. Because Rosneft was hemorrhaging money. Because it is run by a CEO who is more comfortable with mob tactics than spreadsheets. As Luhn writes in Vox:

Rosneft has taken on huge debts in its aggressive expansion and is having to invest far more to keep production up in its declining west Siberian fields. According to Vladimir Milov, an opposition activist and former deputy energy minister who worked with Sechin, he is not a good businessman or manager but rather an “overseer in a labor camp, someone who can intimidate.” He said Sechin is driven by an all-consuming desire to increase his oil empire….

“It’s not a comprehensive strategy, but rather the spontaneous action of a carnivore, of a crocodile,” Milov said. “He sees something and attacks, but there’s no strategy … and the problem of falling production in west Siberia isn’t being solved.”

We still don’t know for sure if Sechin met with Carter Page, Trump’s pro-Russia foreign policy adviser, during his trip to Moscow in 2016, as Steele alleges in what Page calls “the dodgy dossier.” The section of Volume 5 of the Senate Intelligence Report concerning Page is riddled with redactions. But Page certainly was a Sechin fanboy, as noted in footnote #3593: “[Shlomo] Weber said that Page kept going on and on about ‘Igor Ivanovich, Igor Ivanovich, Igor Ivanovich,’ which is how Page referred to Igor Sechin….Weber made it clear that Page never discussed meeting Sechin, but he did talk about Sechin a lot.” Sechin didn’t need to meet Page, as he was already tight with the much more powerful Tillerson, but it stands to reason that he might at least try. Anything to kill the sanctions, re-start the Arctic project, and break his Rosneft losing streak. But even with their own guy in the White House, the sanctions held firm.

With this track record of poor management, why does Putin keep him around? Sechin appears to have as much a hold on Putin as Putin has on him. The two of them are inextricable. Which makes Igor Sechin uniquely dangerous.

One last thought about Putin’s #2: when the Colonial Pipeline was hacked, President Biden said that the culprits were Russian nationals, but not part of the government. That peculiar description wouldn’t exclude Sechin, or hackers working on his behalf. After all, the perpetrators called themselves “Dark Side,” which is the sinister part of the Force controlled by—mirabile dictu—Darth Vader.

I felt like I needed a shower after wading through this disgusting Russian muck. Wow. What a dig you undertook. The extent of depravity is breathtaking. I certainly don't have Russia on MY bucket list!

This is so enlightening yet horrifying. I know we need to know to do something about it but this is just putrid.