My Head's in Mississippi (with Donna Ladd)

To figure out Mississippi is to figure out America.

There is no state as quintessentially American as Mississippi.

The Magnolia State is intimately familiar with the nation’s two original sins—the forced migration and slaughter of Native Americans, and the forced migration and enslavement of Africans. It had, and still has, the highest population of Black residents by percentage, and yet its government has always been controlled in the main by conservative white men, first Democrats and now Republicans—a testament to racist voter suppression tactics that date to Reconstruction. On the other hand, some of the most influential Americans in our history hail from Mississippi: Medgar Evers and Ida B. Wells, Sam Cooke and B.B. King, William Faulkner and Eudora Welty, Jerry Rice and Britney Spears, Oprah Winfrey and Elvis Presley. All that our nation has to offer can be found here, good, bad, and ugly. To figure out Mississippi is to figure out America.

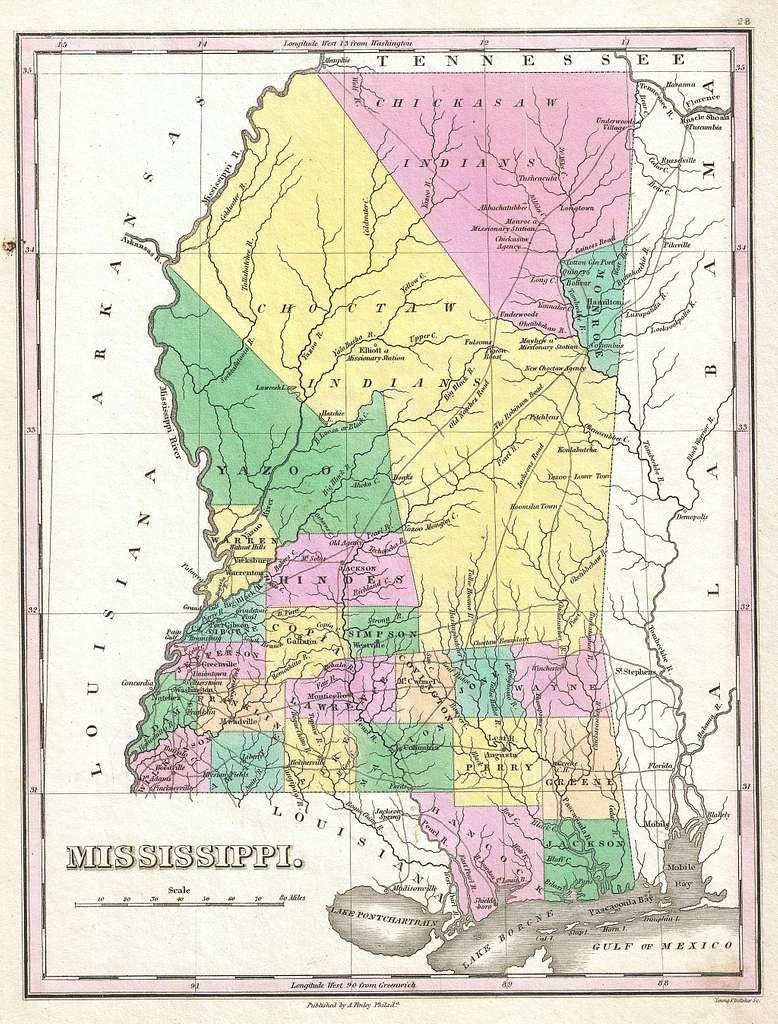

Established in 1821, Jackson, its capital city, is named for the president who signed into law the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which maniacal enforcement led to the forced migration of the Choctaw from Mississippi—part of the Trail of Tears. Over the three subsequent decades, this Native population was effectively replaced by Black slaves—some from Africa, most separated from their families and relocated to Mississippi from elsewhere in the South.

The combination of slave labor, high cotton prices, arable land, and easy access to transportation led to a cotton boom in the antebellum period. Mississippi was, at one time, the wealthiest of the slave states—or, rather, its plantation class was wealthier than its peers. Poor and middle-class whites aspired to own slaves, to found plantations. In 1850, in the Deep South, that was the American dream.

Mississippi was the second state to secede from the Union, following South Carolina. The president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, who previously represented Mississippi in the House and the Senate, made his fortune on a plantation at Davis Bend, south of Vicksburg. A county in the state still bears his traitorous name.

In 1860, Mississippi had a population of 791,305 individuals, 436,631 of them slaves. Blacks comprised some 55 percent of the population after the Civil War. So the minority white ruling class imposed some of the most oppressive voter suppression laws devised anywhere, effectively disenfranchising African-Americans. Racist pro-slavery Democrats would both bully whites into joining the party, while also massacring Blacks in cities like Clinton, Macon, and Jeff Davis’s old haunt, Vicksburg. The “Mississippi Plan” was so successful that it was taken up by other racist regimes in the Deep South.

As Donna Ladd, the editor and executive director of the Mississippi Free Press, tells me on this week’s PREVAIL podcast, the KKK would not just terrorize Blacks trying to vote; it would systematically burn down Black schools throughout the state. It was not enough to deny African-Americans the vote; education must also be denied them.

To prevent the Black majority from gaining a foothold in the state’s politics, racist legislators rewrote the state constitution in 1890, with the express purpose of, as then-governor James K. Vardaman shamefully put it, “eliminating the [African-American] from politics.” And so it did. Some 100,000 Black voters were purged from registration rolls in the state, and by the turn of the century, Black voting had been effectively eliminated. This egregious voter suppression went on for decades, and its impact can still be felt today.

Horrific racism, combined with the lack of opportunity in Mississippi, led to two massive migrations out of the state during the first half of the twentieth century. Black workers who could leave did, settling in northern cities like Chicago or Philadelphia, and later out West in California, where there was more work. Poorer whites did the same.

The civil rights leader Medgar Evers, Mississippi field secretary for the NAACP, was assassinated in Jackson in 1963. The Freedom Summer of 1964, a volunteer campaign by activists to register Black voters in Mississippi, led to the murders of three of those volunteers—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—in Neshoba County that August. (Ladd was born and raised in the county, and the proximity of those murders to her hometown inspired her lifelong commitment to fighting racism). These events spurred Congress to pass the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Mississippi did not officially ratify the Thirteenth Amendment—you know, the one that prohibits slavery—until [checks notes] 2013. The state retained an image of the Confederate flag on its own flag until [checks notes] last year. The Republican Party has a stranglehold on the state’s politics—its governor is Ron DeSantis Lite, Tate Reeves, who is the spitting image of the blow-up Autopilot from Airplane!—but it still has the highest Black population in the country by percentage (37%). Today, Mississippi is one of the poorest states in the U.S., with perennially dismal rankings for education, healthcare, infrastructure, and economy. It ranks first in covid-19 deaths per 100,000, mostly because Reeves, like DeSantis and Texas’s Greg Abbott, refused to implement common sense public health initiatives.

It is easy for white progressives in the North—you know, people like me—to scoff at Mississippi for being backwards, retrograde, absurdly racist. But racism exists throughout the country, even up here, even in big, diverse cities. It does all of us a disservice to scapegoat Mississippi for an attitude that pervades the country, and that is inextricable from our collective history. Would woke Brooklynites feel differently about Mississippi if they were aware that during the Civil War, Mayor Fernando Wood, a Confederate sympathizer, wanted New York to leave the Union and declare itself a free city? That riots broke out in Manhattan about conscription, because white New Yorkers refused to enlist in a war to help end slavery? That until fairly recently, banks would not lend to Black customers unless they were buying apartments in Harlem or Bedford Stuyvesant?

All states have complicated histories. Mississippi’s is just easier to see.

LISTEN TO THE EPISODE

S2 E5: My Head’s in Mississippi (with Mississippi Free Press executive director Donna Ladd)

Description: Mississippi Free Press has done some of the most impactful local journalism in the country. Greg Olear talks to Donna Ladd, co-founder of the Jackson Free Press and executive director and editor of MFP, about her remarkable origin story, racism in the Deep South vs. racism in the North, systemic sexism, the misogyny of the media, a new approach to journalism, Tate Reeves and the political landscape in Jackson, and the complexities of the Magnolia State. Plus: a web hosting company for monsters, by monsters.

Donna’s Twitter page:

https://twitter.com/DonnerKay

Mississippi Free Press:

https://www.mississippifreepress.org/

Donna’s piece about her mother, from The Guardian:

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/dec/20/despite-my-mamas-secret-shame-she-was-the-smartest-person-i-knew

Donna on media misogyny, in DAME Magazine:

https://www.damemagazine.com/2019/11/13/the-media-is-misogynistic-by-design/

Donate to MFP:

https://formississippi.networkforgood.com/projects/87723-a-free-press-for-mississippi

Photo credit: 1827 map of Mississippi by Anthony Finley.

I spent many years of my youth in the Mississippi delta. I’ve hoed and picked cotton. I’ve watched cotton gin workers warming up their sweet potatoes for lunch in a stream of hot cottonseed oil. I distinctly remember the smell of magnolia leaves mixed in the humid air with the almost acrid smell of pecans. I have trudged across ditches and flat fields after my grandfather and his white pointers—dogs—hunting quail on raw, cold mornings. Mississippi is haunted, not magical; molasses without the sweet; fertile without the promise. Mississippi is not a state: it is a condition of dichotomies, of hope and hopelessness.

Thanks for today’s article. Yes. Nothing changes in boggy ground, or marshy minds.

I moved to MS when I was 14 and my dad was employed by Ole Miss to teach in the School of Education. I left MS when I was 21, to move to Texas with my husband. I have only returned to visit family there. I taught in the first Head Start program in Oxford and was one of three white teachers in an all Black county school, the year before Oxford officially integrated its public school system. When I left MS for TX (talk about jumping from the frying pan into the fire), I vowed never to return because at that time, I thought it was the bottom of the barrel in almost all things and the racism was sickening. Over time, however, I've seen racism rear its despicable head everywhere and this past year brought to light how pervasive it was. The murder of George Floyd opened my eyes to a side of life that was far worse than I could even have imagined - based upon my short time witnessing it first hand in MS. I appreciate your making the case for MS not being the ONLY state with such an abysmal track record. Thank you. Maybe, once this pandemic has abated, I can visit my mother there in her nursing home.