Dear Reader,

I read “All Summer in a Day” in sixth grade, 40 full years ago. Few pieces of literature have had a more profound affect on me.

Ray Bradbury’s short sci-fi tale of kids waiting for the sun on Venus was an emotional bludgeon. It made me so viscerally upset that it overwhelmed my emotional sensors. I had no desire to read it again, and did not do so until yesterday. There was no need. No work of fiction has stayed with me longer, or popped into my head as frequently.

In my “Sunday Pages,” I’ve shared many pieces of writing that made me cry, or that moved me in some profound way. “All Summer in a Day” is not that. There is nothing beautiful about it, nothing uplifting. It is an unvarnished glimpse at the ugliness and cruelty inherent in some human beings—the sort of ugliness and cruelty that sublime poetry seeks to transcend. Written in 1954—70 years ago last month—it is somehow a story about MAGAs.

I was in an accelerated reading class with a dozen other kids. We were all friends. We occupied a room on the ground floor of the ancient schoolhouse. The desks were rectangular and lined up like coffins. I remember exactly where I was sitting when we read and discussed the story.

“All Summer in a Day” begins in a classroom not unlike the one I was sitting it when I read it, except that the kids were two years younger and the school was on planet Venus. There is a buzz in the room as the students gather to look out the window:

It rained.

It had been raining for seven years; thousands upon thousands of days compounded and filled from one end to the other with rain, with the drum and gush of water, with the sweet crystal fall of showers and the concussion of storms so heavy they were tidal waves come over the islands. A thousand forests had been crushed under the rain and grown up a thousand times to be crushed again. And this was the way life was forever on the planet Venus, and this was the schoolroom of the children of the rocket men and women who had come to a raining world to set up civilization and live out their lives.

Once every seven years, we learn, the rain stops, and the sun emerges from behind the thick Venusian clouds, and, for one single hour, blesses the planet with light and warmth. The kids are nine years old, and were too young the last time the sun showed its face to remember. Margot, the misfit, is the exception:

She was a very frail girl who looked as if she had been lost in the rain for years and the rain had washed out the blue from her eyes and the red from her mouth and the yellow from her hair. She was an old photograph dusted from an album, whitened away, and if she spoke at all her voice would be a ghost.

She had arrived five years ago from Ohio. She knew the sun, was the only one of the children to know the sun. And they hated her for it.

But she remembered and stood quietly apart from all of them and watched the patterning windows. And once, a month ago, she had refused to shower in the school shower rooms, had clutched her hands to her ears and over her head, screaming the water mustn’t touch her head. So after that, dimly, dimly, she sensed it, she was different and they knew her difference and kept away. There was talk that her father and mother were taking her back to Earth next year; it seemed vital to her that they do so, though it would mean the loss of thousands of dollars to her family. And so, the children hated her for all these reasons of big and little consequence. They hated her pale snow face, her waiting silence, her thinness, and her possible future.

And so, the ugliness and cruelty, instigated by the class bully, William:

“All a joke!” said the boy, and seized her roughly. “Hey, everyone, let’s put her in a closet before the teacher comes!”

“No,” said Margot, falling back.

They surged about her, caught her up and bore her, protesting, and then pleading, and then crying, back into a tunnel, a room, a closet, where they slammed and locked the door. They stood looking at the door and saw it tremble from her beating and throwing herself against it. They heard her muffled cries. Then, smiling, the turned and went out and back down the tunnel, just as the teacher arrived.

“Ready, children?” She glanced at her watch.

“Yes!” said everyone.

“Are we all here ?”

“Yes!”

No one in my accelerated reading class didn’t identify strongly with Margot. We were a room full of Margots: unpopular, sensitive, nerdy know-it-alls. But if any of us were in that classroom on Venus, would we have jumped to her defense? Or would we have merely been grateful that the bully spared us?

The rain stopped.

It was as if, in the midst of a film concerning an avalanche, a tornado, a hurricane, a volcanic eruption, something had, first, gone wrong with the sound apparatus, thus muffling and finally cutting off all noise, all of the blasts and repercussions and thunders, and then, second, ripped the film from the projector and inserted in its place a beautiful tropical slide which did not move or tremor. The world ground to a standstill. The silence was so immense and unbelievable that you felt your ears had been stuffed or you had lost your hearing altogether. The children put their hands to their ears. They stood apart. The door slid back and the smell of the silent, waiting world came in to them.

The sun came out.

It was the color of flaming bronze and it was very large. And the sky around it was a blazing blue tile color. And the jungle burned with sunlight as the children, released from their spell, rushed out, yelling into the springtime.

The nameless teacher, who must also have welcomed the oversized sun, never realized Margot was missing. The kids, all of them, were too lost in their own reveries to free her. Sixty full minutes, and no one did a thing. Only when the clouds returned, and the raindrops began again did one of the kids—a girl, notably—realize what they’d done. The story ends like this:

They stood as if someone had driven them, like so many stakes, into the floor. They looked at each other and then looked away. They glanced out at the world that was raining now and raining and raining steadily. They could not meet each other’s glances. Their faces were solemn and pale. They looked at their hands and feet, their faces down.

“Margot.”

One of the girls said, “Well…?”

No one moved.

“Go on,” whispered the girl.

They walked slowly down the hall in the sound of cold rain. They turned through the doorway to the room in the sound of the storm and thunder, lightning on their faces, blue and terrible. They walked over to the closet door slowly and stood by it.

Behind the closet door was only silence.

They unlocked the door, even more slowly, and let Margot out.

What happens next is left to our imagination. Hollow apologies. Shame. Guilt. Punishments that do not fit the crime. William is a bully, and is probably incapable of contrition. The other kids, the ones with souls, would never be able to forgive themselves. And Margot, I can’t even imagine. She was already depressed, gloomy, isolated. That would have killed whatever was left of her spirit. How could any of them have gone on with their lives after that?

Understand: I hate this story. I hate its emotional manipulation. I hate the austere economy of its language. I hate the rain. I hate the teacher. I hate William. I hate the other kids. I hate Margot’s parents, for bringing her to Venus in the first place. Most of all, I hate Ray Bradbury for reminding us—in 1954, not yet a decade after the Holocaust—that yes, human beings are capable of great cruelty; yes, human beings are easily swayed in social situations to behave abominably; yes, bullies have too much power; yes, authority figures are often useless or ineffectual; yes, missing out can be soul-destroying; and no, goodness does not always prevail.

On Thursday, my friend Diana Spechler wrote a piece on her excellent Substack, brilliantly titled “Turn Around, Bright Eyes,” about how she missed the eclipse. I’d driven to a place in the path of totality, so I could see the sun and moon look like a ring light; she boarded a plane and fled the path of totality, right before the cosmic event happened in the city where she lived, and missed the whole thing.

As I read the piece, I kept thinking about “All Summer in a Day,” and was extremely gratified when she alluded to it. Diana and her fellow passengers on the plane “were the girl in that Ray Bradbury story set on Venus,” she wrote, “whose classmates lock her in a closet during the one hour of sunlight they’ve known in their lives.” And, a few paragraphs later: “I think I was born with the sense that the party is always raging in some other house, that the story is unfurling while I’m stuck in a closet. Is any human spared that worry?”

I emailed her: “I’m so glad you mentioned the Bradbury story. I read it in sixth grade and I still think about it every once in a while: the cruelty of the kids, the horror of missing out, and how all of human nature, the mean and the sublime, is contained in that story. It really affected me. I’m afraid to read it again.” She wrote back: “The Bradbury story has haunted me my whole life!”

So I’m not the only one.

As he aged, Bradbury got more and more politically conservative. He voted twice for Nixon. He thought Reagan and George W. Bush were wonderful. In 1994, he was asked how Fahrenheit 451, his 1953 novel about book-burning (which I’ve never managed to get through), held up: “It works even better because we have political correctness now,” he said. “Political correctness is the real enemy these days. The black groups want to control our thinking and you can’t say certain things. The homosexual groups don’t want you to criticize them. It’s thought control and freedom of speech control.” That is veering into Elon Musk/ featured-guest-on-Bill-Maher territory. That’s three quarters of the way to “drain the swamp.”

Reading the story now, as a middle-aged man, I find it less horrifying than I did when I was 12, when things that I loved or desperately wanted to do took on an outsized, life-or-death importance. For better or worse, age tempers that childish feeling of unbridled, Christmas morning excitement. We’ve all tasted disappointment too often. The fear of missing out—FOMO, to the Millennials—isn’t as acute. As J.B. Priestly wrote, “One of the delights beyond the grasp of youth is that of Not Going.”

I still can’t decide if “All Summer in a Day” is an artistic work of genius because it affected me—and Diana, and many thousands of other readers besides—in such a profoundly negative way, or if, by subjecting us to such a bleak tale of sadism and hopelessness, Bradbury is no better than a literary William, bullying us with his florid sentences. Is it expert craftsmanship to end the story without telling us what happens next, and thus leaving the denouement up to our imagination, or is it just lazy writing?

More importantly, is it valuable to offer a story completely devoid of hope? Why should I be made to think about something this awful at all? What’s the point, Ray?

I much prefer the opening line from Stephin Merritt’s “Sweet-Lovin’ Man,” which alludes to the Bradbury story, but with a twist:

There’s an hour of sunshine for a million years of rain,

But somehow it always seems to be enough.

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was the photojournalist Sandi Bachom:

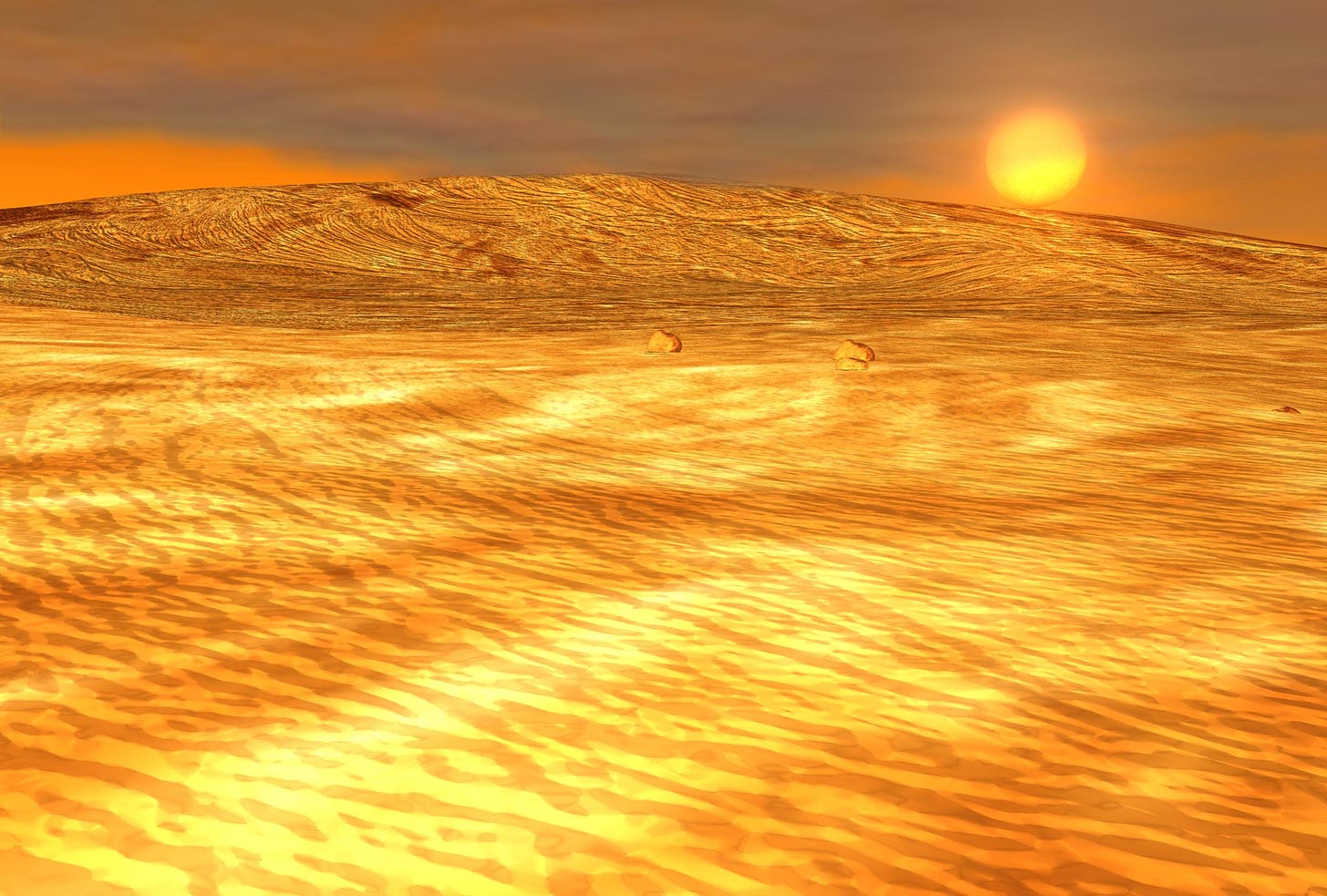

Photo credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab. Artist’s rendering of surface of Venus.

All week I’ve been living through FOMO. I didn’t get to a store to find those stupid glasses. We didn’t have a total eclipse in Colorado. My friend traveled all the way from Bellingham, WA to Texas to see it. I saw reports of large gatherings suddenly gasping at the sight and listened to the Annie Dillard descriptions. I missed it and have felt a little like Margot this week. Now, suddenly, I feel a little better after reading your post. I will probably not live long enough to make it to the next total eclipse, but today the sun is shining so brightly. The sky is so blue (as it occurs only in Colorado). My peach tree has just exploded in blooms. So there, to all you bullies!! (Oh and you know who will be in court tomorrow….)

Mobbing is cruel and surely, many of us have experienced it. Luckily, my parents taught me to stand up to them, so here I am still kicking ass 😊 #Resist