My father died yesterday.

He had been sick for some time—I wrote about him on “Sunday Pages” last Father’s Day—but over the last few months he deteriorated rapidly. He was moved to hospice on the 29th, and managed to hang on through the 30th, which is my mother’s birthday. My brother sat with him both of those nights. The morphine did what morphine does. He did not wake up, did not open his eyes.

After first seeing him when I got to town on the 30th, I went to the hospital yesterday morning, when visiting hours opened at 10. I played him a seven-song Roy Orbison playlist. And at 10:28, right after the last song ended, he was gone. That’s what I texted everyone: He’s gone.

His suffering is over. He is at peace. And my mother, who has cared for him round the clock for years now, is relieved of that duty. She no longer has to care for this man she has known, and loved, since they were sophomores in high school. I was alone with him when he died, and I’m grateful that I was there. It was one last gift he gave me.

You know how a lot of creative people have terrible fathers? Dads who are petty, who don’t believe in them at all, who scoff at their ambitions, who delight in their disappointment, who call out their failures? My father was almost comically not like that. He was exactly the opposite. I don’t know that he ever really understood what I do, all of the projects that I was undertaking at any given time—we had the same name, but not the same pursuits—but he always encouraged me, believed in me, supported me. I felt protected and nurtured and loved. I felt taken care of. My father would have done anything for me and my brother. What a privilege, what a gift, for us to have that knowledge, that certitude! There is nothing more meaningful a parent can give a child. I don’t know how he knew to be that way. Certainly not from his father, who was the self-centered, tyrannical, belittling patriarch we find so often in novels and films and the songs of Bruce Springsteen.

I’d been fumbling for the right word, and my wife found it: unconditional. He loved unconditionally. If you were in the circle, you were in the circle. She said, “He was non-judgey. He always made me feel good about myself.”

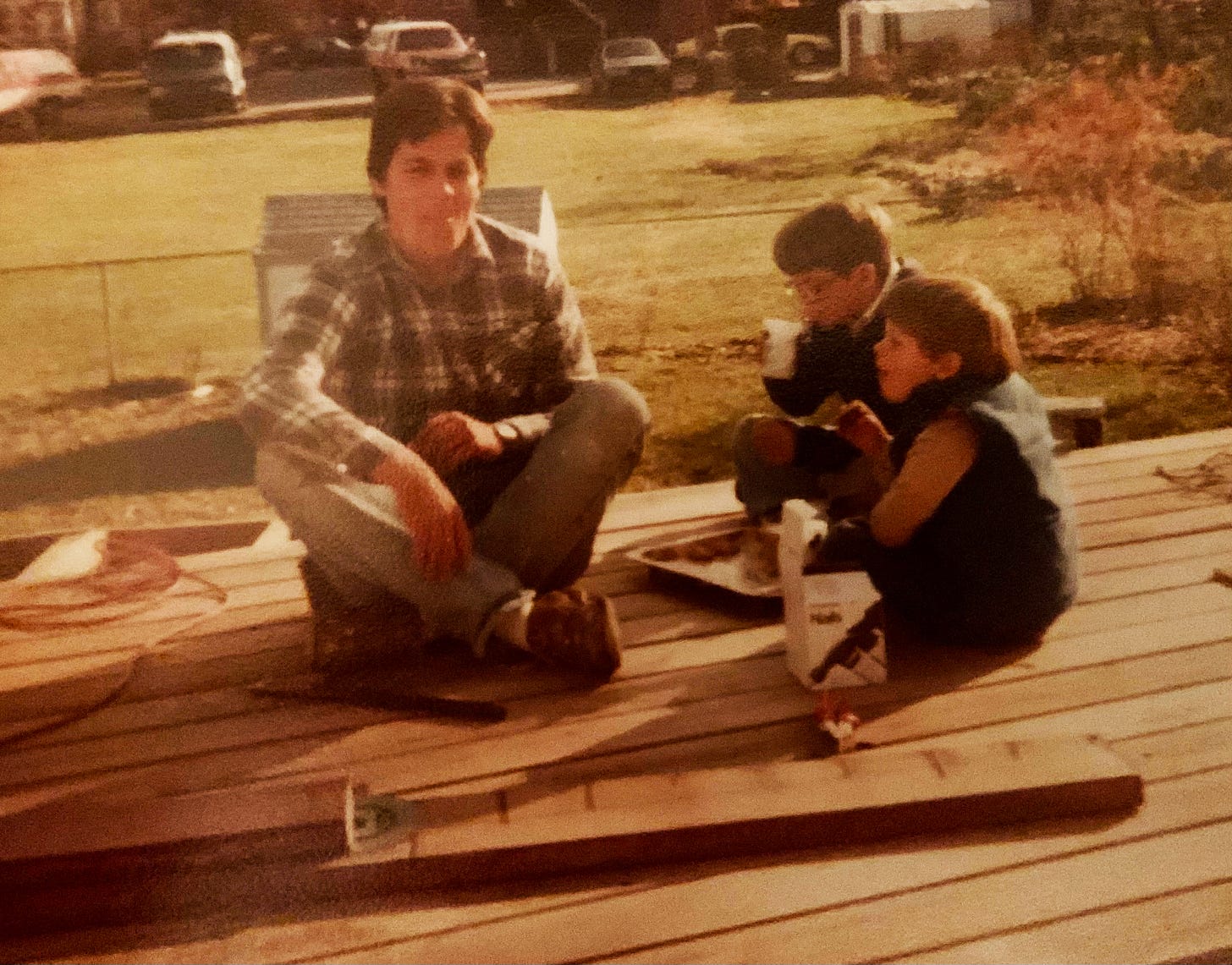

My father was a do-it-yourselfer extraordinaire. That was where his creativity expressed itself. When it came to home improvements, there was nothing he couldn’t do. He did roofing. He did plumbing. He did masonry. He re-wired electrical circuits and rebuilt decks and installed kitchen cabinets. Once, in college, the drain in our bathtub stopped working; I called him, asking what to do, and he walked me through it, in the days before FaceTime, describing each piece of the apparatus, so foreign to me, as if he was seeing it with his own eyes. It was astonishing to me, that he knew how to do all that. This wasn’t his job—he worked in property/casualty insurance—but he somehow knew.

From the time our young family moved into the new prefab in 1978, the Olear house became a sort of DIY laboratory. There was always some construction project going on, usually involving something heavy, like gravel, sheetrock, Masonite, and cinder blocks. In the photo above, taken just before my tenth birthday in 1982, we are eight feet in the air on the first of many decks he would erect in the backyard. He once poured concrete by the back door just to rent a jackhammer a few months later to remove it. He re-did the basement floor no less than seven times; two weeks before his death, he was urgently trying to get someone to re-do the perfectly nice kitchen flooring, perhaps out of force of habit. I did not inherit this gift, alas, although I did renovate our bathroom two years ago—and it pains me that he never got to see it.

As soon as I walked in through the garage on Friday, I was struck by how the house was basically a Greg Olear, Sr. museum, that he had modified every nook and cranny of the place, that his tools still lay all over—and that he would never use them again. When I go, my kids will have my books, my guitar, and a bunch of computer files. But my dad left physical space that he created. He left architecture. As I type this, I’m sitting in the office he made, looking at the knickknacks on the shelves he built, occupying his space. The house is a shrine to his creativity. No wonder my mother never wants to move.

My father was very funny—and not at all in a “dad joke” kind of way. He hated that shit. (His funniest moments usually came when he was driving and cannot be repeated here.) His sense of humor was darker than mine. Once, when my friend Chris was staying at our house right after graduation, we were in the kitchen and heard him down the hall, howling with laughter. We went to see what he was watching that inspired him to crack up so loudly. The answer: Outbreak, with Dustin Hoffman. Which is, um, not a comedy. But he was laughing so hard he was crying.

My father was a loving, giving person, generous with his time and money and attention. He was always ready and willing to drive you to the airport, help unplug a clogged drain, paint your living room, slip you some cash on your way out “for gas,” and lend an ear or a hand. Not being able to fill that role was extremely frustrating for him these last few years. If I’m at all a good guy—and I’m not sure I am, although I try my best—it is because my father provided that example, especially in how he treated my mother, who has been unequivocally his favorite human since 1964.

That it happened on New Year’s Eve was incongruous, adding a layer of weirdness to what was already a weird day—like our son being born on Christmas, but leaving rather than arriving. He died on the last day of the year! All day yesterday, messages of condolences came in, along with festive wishes of Happy New Year from my friends who didn’t know.

I think, if he had any control at all over when he passed, he would have wanted to wait until after midnight on December 30th. He would not have wanted to die on my mother’s birthday.

But there was a residual effect to lasting until New Year’s Eve, one I had not anticipated: the day ended, literally, with fireworks. It was quite a send-off.

Photo: my father with me (in glasses) and my brother, October 1982.

Beautiful tribute, Greg. My condolences to you and your family.

So young. TOO young. I wept for my own dad as I read your beautiful tribute to yours. Too few of us know that non-judgey, unconditional love - his gift to you.