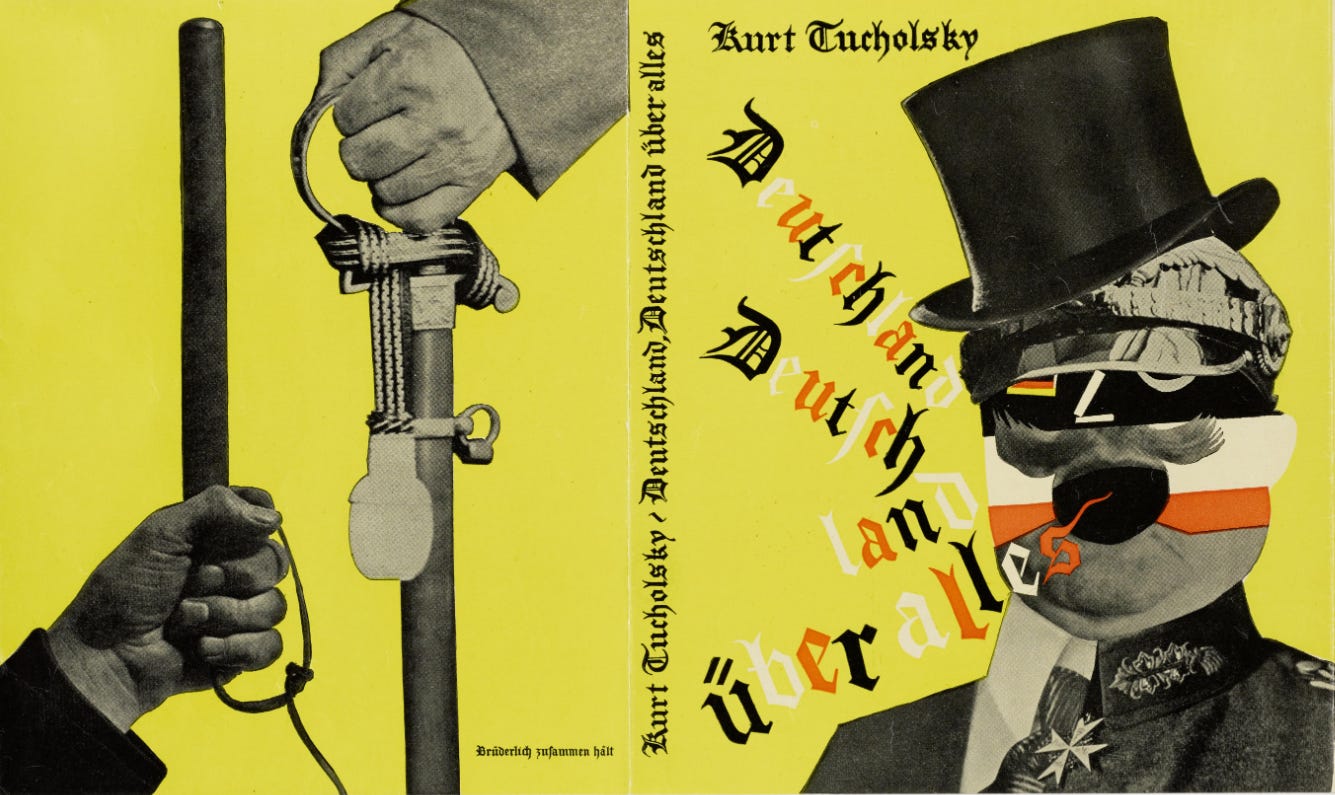

Sunday Pages: "Deutschland, Deutschland über alles"

A picture book by Kurt Tucholsky and many photographers, assembled by John Heartfield

Dear Reader,

Kurt Tucholsky was posthumously described, rather unkindly, as “a fat little Berliner who wanted to stop a catastrophe with his typewriter.” He was a journalist, a social critic, a satirist, a poet, a novelist—a true man of letters. A German Jew living in Berlin, the slang of which city he incorporated into his work, he saw the writing on the wall early, and set about warning whoever would listen of the dangers of ascendant Nazism.

By the late twenties, his country was in a precarious position. Germany had lost the Great War and was saddled with reparations it could not comfortably afford. Hyperinflation—actual hyperinflation; not what Jack Dorsey and the other American tech bros call hyperinflation—wreaked havoc on the economy in 1923. The Weimar Republic was a noble failure.

All of this I knew before this morning, when I began reading about Tucholsky from my hotel room here in Berlin. What I didn’t know was what the late twenties were like in Germany—how uncomfortably similar to America now. The government was reluctant to prosecute well-to-do criminals. Police brutality was a real problem. The courts were riddled with reactionary judges who sympathized with violent rightwing criminals, especially if their violent crimes were perpetrated against leftists.

In 1922, the foreign minister, the left-leaning Walter Rathenau, was assassinated by rightwing extremists—although I suppose that, since Hitler was already the head of the National Socialist party by 1922, we can safely call them Nazis. Tucholsky wrote a poem about Rathenau that was critical of the politicians running the government: the non-Nazis, whom he found weak, effete, reluctant to stand up against the burgeoning authoritarian movement:

Get up once! Hit it with your fist!

Don’t fall asleep again after fourteen days!

Out with your monarchist judges,

With officers, and with the elite

That lives off of you and that sabotages you and

Smears swastikas on your houses.

You smash the secret associations to pieces!

Bind Ludendorff and Escherich’s hands!

Don’t let the Reichswehr mock you!

She has to get used to the Republic.

Hit! Hit! Pack it up properly!

They all chicken out. Because there is no man there.

There are only snipers. Grab it tightly—

your house will burn if you let it smolder now.

Break the paragraph loops.

Don’t fall into it. It must succeed!

Four years of murder—that’s enough, God knows.

You are about to take your last breath.

Show what you are. Judge yourself.

Die or fight!

There is no third way.

I don’t need to tell you that this exhortation fell on deaf ears. Tucholsky spent the rest of the decade railing against Nazis, political violence, and war, and fiercely defending human rights, democracy, and the existing government. This was in vain. “They are preparing for the journey to the Third Reich,” he wrote, before the Third Reich was a thing. And, later: “You don’t whistle against an ocean.”

Plenty of otherwise decent Germans, more than there should have been, were down with Hitler. Only he could fix what was wrong. Only he could Make Germany Great Again.

In 1929, Tucholsky joined forces with John Heartfield—real name Helmut Herzfeld—a sort of proto-meme artist, to produce Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, a book with pictures and satirical captions that advanced that form of protest writing. (The photo above is one of the covers made for the book, using the collage art.) That same year he fled to Sweden to avoid his own prosecution on trumped-up charges. He died there, in Gothenburg in 1935, of an overdose—possibly accidental—of the barbiturates he was using to relieve the pain from his chronic stomach problems. That was four full years before the invasion of Poland, but he knew what was coming. He had no illusions.

One of the many ugly things about MAGA is its attempt to appropriate all patriotism: to claim the flag as their own, to insist that they are the true Americans. With this in mind, it is a passage at the end of Deutschland, Deutschland über alles I’d like to share with you today:

And here is the confession that this book should lead to: Yes, we love this country. And now I want to tell you something: It is not true that those who call themselves “national” and are nothing but military bourgeois [read: Nazis] have claimed this country and its language for themselves. Neither the government representative in the frock coat, nor the senior teacher, nor the men and women in the steel helmet are Germany alone. We’re still here too. They open their mouths and shout: “In the name of Germany...!” They shout: “We love this country, only we love it.” It is not true.

It was not true in Germany in 1929, even as Hitler and his Nazis were gaining strength. And it is not true in the United States, even as our own orange Hitler attempts to reclaim the White House and end our democracy.

We’re still here too. And we’re not going anywhere.

Thank you for this. I was born in 1954 and grew up in France reading and hearing about the years before and after Hitler came to power. Ever since 2015 when you know who announced that he was going to be president, I have had the awful feeling of being thrown back into the thirties in Europe. I fear for my grandchildren but I want to keep hoping that we can keep our democracy.

There are many parallels. As a Jew, the child of a member of the French Resistance and concentration camp survivor and of a refugee, both originally from Austria, it has been hard since Trump arrived on the political scene not to be acutely aware of them. There is an interesting difference, though, that you touch on. As you say, Germany in the 1920s was experiencing real economic distress both because of the Depression, which was not restricted to the US, and because of the reparations demanded by the Treaty of Versailles. Economically, at least, there is no parallel between the desperation that the Germans (and many Americans) felt at the time, and now. Yet, somehow, among those with whom he resonates, Trump and his ilk have exploited the feeling of "we aren't getting everything we want all the time" to a degree that Hitler was able to do with people who really had nothing.

There is a paradox, too. Similar circumstances gave the Germans Hitler and us Roosevelt. Now, Germany, despite a rise in the right, remains a staunchly democratic country while here our democracy is being eroded albeit by a minority that games the system. It makes me wonder whether the darker side of winning, even in a truly righteous cause, isn't that it permits us not to feel that we need to learn the lessons of history.