Dear Reader,

On the first of November, 1871, the temperance activist and writer Mary Helen Peck Crane, wife to a Methodist minister, gave birth for the fourteenth and final time. She was 45 years old. Her tenth, eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth children had all died in infancy—diphtheria epidemics raged frequently in big cities like Newark, where they lived. Probably she expected that the new baby, sickly as he was, would meet the same fate. He did indeed die young; he was just 28 when tuberculosis killed him in June of 1900, 124 years ago this week. But in his short life, Stephen Crane, the Boy Who Lived, became one of American literature’s most important figures.

In the traditional canon, the timeline goes like this: Of the first generation of U.S. writers, Emerson was born in 1803, Hawthorne a year later, Longfellow in 1807. Edgar Allen Poe was born in 1809—much earlier than I thought. Harriet Beecher Stowe was born in 1811, Thoreau in 1816, Melville and Whitman both in 1819. The Gilded Generation gave us Emily Dickinson in 1830, Louisa May Alcott in 1832, Mark Twain in 1835. Henry James was born in 1843, Kate Chopin in 1850. Later, the legendary Lost Generation provided Hemingway, Nabokov, Hart Crane, and E.B. White, all born in 1899, three years after Fitzgerald.

Along with Paul Lawrence Dunbar (1872), Jack London (1876), and Upton Sinclair (1878), Crane occupied the relatively quiet “Missionary Generation” period between the assassination of Lincoln and the assassination of McKinley. The work of this crop of writers has generally had less staying power; Crane wrote The Red Badge of Courage, one of the great war novels, and a seminal work of American realism, in 1895, and was more or less forgotten by the time The Great Gatsby was published 30 years later.

But Stephen Crane lived quite a life. He was mostly raised by his sister Agnes, 15 years his elder. He moved around: the suburbs of Newark; rural Sussex County; Port Jervis; Asbury Park, where his house still stands. He played, and was reportedly quite good at, baseball. He spent a few semesters at Syracuse University, where he mostly skipped class to play catcher on the club team and carouse with his fraternity brothers. He quit school—he called it “a waste of time”—and became a journalist, following in the footsteps of his older siblings. He was, as a contemporary put it, attractive without being handsome.

Crane wound up in New York City—which, in the late 19th century, was still only Manhattan—where he spent most of his time reporting on, and indulging in, the decadence, poverty, criminality, and allure of The Bowery. His first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, was drawn from his immersive reportage.

In 1896, during his brief period of fame and solvency, Crane was involved in a highly publicized scandal. In the wee hours of September 2, he was escorting three sex workers out of a notorious club called the Broadway Garden, as one does, where he intended to see them safely installed in a cab. A cop, a violent lout named Charles Becker, swooped in to arrest the women for solicitation. Crane, who must have been at least a little loopy, told the cop, basically, to fuck off—no one was being solicited, the women had done no wrong. But Becker detained one of them, a beauty with the delightfully 1890s name of Dora Clark, and took her to the station. My take on this is, Becker was titillated by what he saw and would have probably released her in exchange for sexual favors—if Crane had not been there, and followed them to the station, and given a sworn statement, and gotten her discharged.

Later, Dora Clark pressed charges against the policeman, for false arrest. Becker was so incensed by this consequence of his corruption that he tracked her down and roughed her up, right on the street, while onlookers watched in horror. Against the advice of his friend the police commissioner—Teddy Roosevelt, because of course it was—Crane testified at the trial. To prepare for the defense, cops raided his house, ransacked his shit, and confiscated his papers, to secure evidence that he was too debauched to take seriously as a witness.

“I only frequented those nightclubs and got wasted and hung out with the sex workers for research, for my writing” went over about as well in 1896 as it would in 2024. The jury took the word of the rapey cop who beat Dora up over a professional journalist and minister’s son who became a famous novelist by writing books known for their unflinching realism. (Not all New York juries are as reliable as the one that convicted Trump.) Becker was acquitted, Crane’s reputation ruined. A wag at a Chicago paper quipped, “Stephen Crane is respectfully informed that association with women in scarlet is not necessarily a ‘Red Badge of Courage,’” which is the sort of unfunny joke Jesse Watters or Greg Gutfeld would make. The columnist may as well have accused Crane of being too woke.

Crane fled. He covered the war in Cuba. He was shipwrecked and floated on a dinghy for a day and a half on the open sea before swimming to shore at Daytona Beach, having lost the gold he’d been given as payment. He frequented brothels. He hooked up with women of ill repute. He hooked up with men of ill repute. He fell in love with the owner of a Jacksonville bawdy house, Cora Taylor, who was technically still married to her second husband, and whisked her away to Europe. In England, he became friends with Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford and H.G. Wells and Henry James. He covered the war in Greece, where Taylor became the first-ever woman war correspondent. He racked up debts he could not pay. He contracted tuberculosis. He cranked out novels and short stories and poems, in a futile attempt to pay his bills. In the German spa town of Badenweiler, he suffered a pulmonary hemorrhage and died, 18 months before his thirtieth birthday.

I relate all of this because Crane lived a fascinating, full life, but also because his experiences were peculiar to a certain dark American era: the McKinley period, which is the point in time Trump and the Project 2025 weirdos want to bring the country back to. Would Helen Crane have had 14 children if she had access to the birth control and abortion clinics that the Leonard Leo extremists want to take away? Would the four infants before Stephen have died in childbirth, if they had been given vaccines that MAGA (and RFK, Jr.) don’t believe in? Would a famous writer have been permanently scandalized for studying—and standing up for!—sex workers? Would it fly that an independent, hip, adventurous woman like Cora Taylor was not able to legally vote? Would that shithead patrolman have been acquitted, if the video of him beating up Dora Clark went viral on social media? Okay, fine, yes, the cop would have gotten off, #ACAB, but there would have at least been protests about it. In spite of all the damage Trump and his minions have wrought, life is objectively better now than it was in the 1890s. We need to keep it that way.

In 1895, Crane published a book of poems. I stumbled upon one of them in this old poetry anthology I bought at the book fair last year: The Book of American Poetry; Edwin Markham, editor; Wm. H. Wise & Co., publisher, 1934. It is a thick tome, with yellowed pages, and contains works by poets I have never heard of before, mostly because their poems are not very good. There are hagiographical odes to Lincoln, overtly religious doggerel, and assorted other hokum. But there, in the short section of Crane’s, is a wonderful little poem whose last two lines I immediately recognized as the title of the Joyce Carol Oates novel Because It is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart. I think my parents had a copy of that lying around, because the title really stuck with me. I remember wondering what on earth the words meant, and why she selected something so long and so odd as a title. Seriously, Joyce, WTF? But once I read the entire poem, I understood.

The poem’s original title, per Markham, is “Eating,” although elsewhere it is called “In the Desert.” It goes like this:

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter—bitter,” he answered;“But I like it

“Because it is bitter,

“And because it is my heart.”

That’s heavy, right?

Having just published a book whose title is taken from a poem, I believe that the “image our of Spiritus Mundi” that came to Yeats in “The Second Coming” was inspired by this “bestial” man “squatting upon the ground.” There’s simply too many similarities for the one not to have been at least partly influenced by the other.

“Eating” can be read in a multitude of ways. Despite its “bestial” mien, the “creature” is presented as having wisdom. There is something to be learned from what it is doing. Perhaps it is a vision of the poet’s own essential being that he glimpses, in this arid place of heat and desolation, where nothing grows.

The experiences that we have as human beings are often unpleasant. They can leave us full of regret and loss: jaded, mournful, despondent, angry—and, yes, bitter. But they are our experiences, and ours alone. That makes them special. And all we can do with these bad feelings is consume them, feed on them, take spiritual nourishment from them, use them to sustain our continued existence, and, hopefully, learn from them.

Too, the bitterness is a mark of honor for having survived—a badge of courage, if you will. That’s why the creature “likes” it. Not because it tastes good, but because it belongs to it and it alone.

For such a strange, cryptic poem, the message is quite simple: Eat your heart out.

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Tony Michaels, host of The Tony Michaels Podcast:

I was a guest on Helen’s excellent Irish Granny Tarot show, where we talked about Rough Beast—and, at her request, I give a dramatic reading of the Yeats poem.

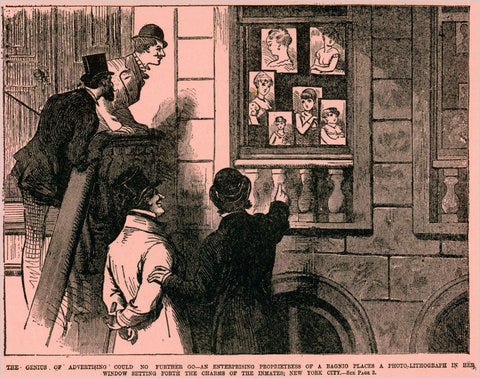

Photo credit: A drawing titled “The Genius of Advertising” from an 1880 issue of the National Police Gazette shows men outside a brothel gazing at pictures of some of the attractions awaiting them inside. Via New York Times.

This is a Sunday post perfectly suited to an English major’s heart. I’m going back after my other necessary chores to watch everything you’ve given me.

Thanks for the literary history lesson. My wife and I both had moms who were public school English teachers. Our daughter is a university English professor. This was a nice treat on a Sunday morning. I knew a bit about Crane, and of course read The Red Badge of Courage. I had never read that poem. Wow, Crane said a lot in a few words, and your beautiful interpretation was just as good. Thank you for this today.

This has been a welcome respite from the shallow and I believe deluded and depraved chaos around us. I never believed my fellow Christian citizens would decide electing the Antichrist as president was a great idea………..3 times!