Sunday Pages: "Empress: The Secret History of Anna K"

An excerpt from my new novel.

Dear Reader,

The first “Sunday Pages” appeared on March 15, 2020. My friend Laura Bogart—not to be confused, in any way, shape or form, with the seditious Congresswoman from Colorado—was putting out a novel just as the world was shutting down. I wanted to help get the word out, so I ran an excerpt, hoping that my readers would enjoy a little literary diversion.

In the months that followed, “Sunday Pages” evolved into what it is today: my weekly excuse to wax poetic, gush about literature and music and films and art that have moved me, and give myself—and you, Dear Reader!—a respite from the heartache and despair all around us. Always, these are my favorite pieces to write. Sometimes, I don’t know what I’m going to write about until I wake up Sunday morning. Almost invariably, those turn out to be the most popular posts.

Although I am, or used to be, a writer of fiction, I have resisted the urge to run my own work on Sundays. I’ve done it twice, I believe, in over 100 dispatches. I hope that you’ll forgive me for breaking my unwritten rule a third time, on the occasion of releasing my third novel. It is with great pleasure—and even greater trepidation—that I present Empress: The Secret History of Anna K.

To organize my thoughts about the book and the long process of writing and publishing it, I’m going to appropriate a device we used at The Nervous Breakdown back in the day: the self interview. Here we go. . .

Wait, why are you so nervous?

Two seasons ago, the New York Knicks, my favorite team in my favorite sport, made the playoffs for the first time in many years, with a collection of players I adored. As I tuned into the first-round series against the Atlanta Hawks, my stomach was tied in knots. It had been so long since my team was in the playoffs that I’d forgotten the agida that goes along with it. Putting out a book is the same uneasy feeling. You simultaneously want everyone to read it, while at the same time dreading the prospect of anyone reading it, because what if they all hate it? And then, even worse: what if no one reads it at all? Yes, I crank out column after column at PREVAIL, and these make me anxious too sometimes, but this is a different kind of anxiety. I’ve been a nervous wreck all week.

Your last work of fiction dropped in 2009. Why did it take so long for Novel #3?

Once upon a time, I was a novelist. From my senior year in college until 2016, my creative life revolved around whatever book I was working on. Nothing was more important to me. Even the jobs I took were to inform my writing. I went into human resources mostly because the plot of my first published novel, Totally Killer, was set in a Manhattan employment agency, and I wanted to learn more about that world. While I did not become a father to write Fathermucker, my second published novel, the experience certainly helped.

I had some modest success. I sold the film rights to both of the books. Both were published in French, which made my writer friends jealous. In 2011, I went to Paris and Lyon on a book tour for Totally Killer—easily the highlight of my literary life. Book #2 was published in German as well. And, for one glorious week, Fathermucker snuck onto the L.A. Times best-seller list. Never mind that this was more an indictment of that esteemed newspaper’s methodology for calculating sales than an accurate assessment of units moved; I will forever be, even after my death, an “L.A. Times best-selling” author. As Kevin Garnett said while holding the trophy after leading his team to the NBA championship: “It is like knowledge. Once it is obtained, it is obtained.”

But the third novel proved more elusive. There were many stops and starts: projects either finished or almost finished, only to be discarded. My agent lost faith in me, in her ability to sell my stuff. I was not getting any younger—publishing houses, like all entertainment companies, love a shiny new object—and my first two books, while not complete busts, did not take off in any reputation-making way. It was going to take a truly special effort to get back on track.

And then, in a flash, I knew what to do. I’d produce a big, ambitious work of historical fiction! I’d write a tale of the First Crusade from the Byzantine point of view, centered around a (fictitious) romance between Anna Komnene—the firstborn daughter of the Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and the author of the Alexiad, an exhaustive history of her father’s long and eventful reign—and Bohemond of Antioch.

The original plan was to do this many years in the future, when I was retired and had more time to do the research. Then desperation (a novel I’d just finished was rejected by my agent, on account of it being not good) and inspiration (the idea of having Anna be the narrator, and the novel itself being a “real” text found in a lead pot in Istanbul) converged, and in 2015-16, I banged this puppy out in 18 months, writing only in the early morning, reading Byzantine history books in the evening, working a fulltime job, managing a literary website, and coaching several of my kids’ basketball teams.

Some days, especially early on, I wrote as if possessed. Despite the sometimes dark nature of the narrative—the Byzantines were big into eye-gouging, and medieval life was hard, especially for women—I have never enjoyed writing fiction more than I enjoyed writing this. I’ve never felt more sure of a project I was working on. But my agent couldn’t sell it. “You’re not known as a writer of historical fiction” came a few years before “You’re not an expert on Trump/Russia” in my numerous rejections by numerous publishing houses and subsequent literary agents; maybe if I were a handmaiden Supreme Court Justice or a corrupt Trump White House official, I’d have had better luck.

Plus, no one wanted to read it, because, like, it’s long. The literary appeal of the subject (no one knows anything about the Byzantines!) was also a commercial red flag (no one knows anything about the Byzantines!). Then Trump happened, my writing career went in an unforeseen new direction, and Anna’s story really did get buried—on my hard drive, not in a lead-sealed pot, but buried just the same.

For almost two years, back in the Before Times, I put my heart and soul into this book. I wanted to set it free into the world—to give it life. More specifically, I wanted to share it with you, Dear Reader, on “Sunday Pages.” So I figured, to hell with it—if traditional publishers don’t want it, I’ll do it myself, like I did with Dirty Rubles. And here we are.

What’s the book about?

Empress presents as the lost autobiography of an heir to the Byzantine Empire, and her impossible path to power. (And thanks to Jim Infantino for coming up with that logline.) Here’s what it says on the back cover:

In 2016, construction workers in Istanbul made a remarkable discovery. Sealed in a lead pot twelve feet underground was a lost manuscript by the Byzantine princess and historian Anna Komnene—an intimate account of the royals who held sway in Constantinople in the High Middle Ages. This is the first English translation of the Anekdota, or Secret History, of Anna Komnene (1083-1153). Not since the Dead Sea Scrolls were unearthed at Quran has an archeological find threatened to upend everything we know about a heretofore-fuzzy historical period.

My friend Ronlyn Domingue, who wrote The Mercy of Thin Air and the Keeper of Tales Trilogy—which are all great novels you should read!—calls Empress a “magnificent work of imagination and scholarship.” My friend and occasional podcast guest Aja Raden says, “With the imagination of a novelist and the exacting attention of a journalist, Greg Olear has written a transportative tale of sex, violence and politics.” And just yesterday on The Stuttering John Show, Richard Ojeda declared that if I wrote a 700-page book, then “it’s 700 pages of some good shit.”

Why does this cost more than Dirty Rubles?

My last agent said that I should chop this baby up and make it two books instead of one. You make more money that way, she said. Because I am bad at business, and disinclined to chop up babies, I opted not to do that. But it really is like two books in one, so I decided to use the French model of putting out a big, thick paperback as a first edition. (Plus, Amazon does exact its pound of flesh.)

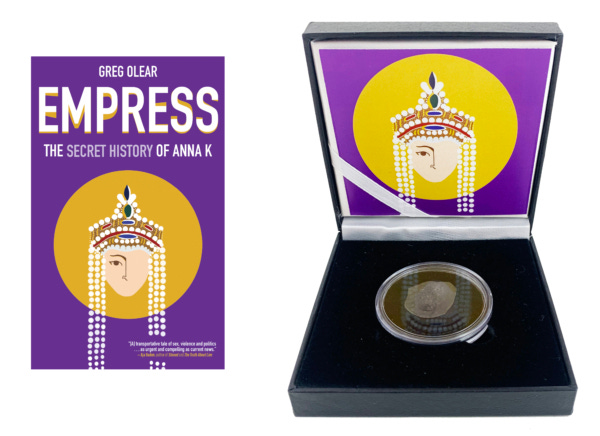

What if I want a signed copy?

I’ve put together a special package: a signed, inscribed copy of Empress, plus a genuine Byzantine “cup coin”, in a snazzy package, that circulated at the time that Anna K. would have been writing her Secret History:

This is also a good way to buy the book if you don’t live in the United States and can’t get it on Amazon. Or if you’d rather buy a copy from someone other than Amazon. Or if you really want to support my work. (Note: it will take an extra week or two for these to go out, as I’m still waiting for my author copies to arrive from the distributor).

Is Empress available as an audiobook?

Not yet. However, if you prefer to listen, I’ve created an audio of the introduction, preface, and first chapter. (Anna’s narration is read masterfully by my very talented friend Alison Weller). You can download the audio file here, or listen on YouTube:

Thanks for indulging me, Dear Reader. It’s a gift to be able to write these columns every Sunday, and to engage with such a wonderful, supportive community. Next week, I’ll be back with non-Greg material.

But for today, here is a little taste of the new book:

Preface

The stream of time will wash away the dark stain of our delible memory, sure as the rushing river smooths the stone on its bank. No man mortal or otherwise is impervious to these relentless waters: even the gods are forgotten. This, the astute reader will recall, was my stated motivation for writing the Alexiad—to give account of the deeds of my esteemed father, the great Emperor Alexios Komnenos.

It is with some irony, then, that my own memories are refusing to wash away, or at any rate are not washing away fast enough. Time takes its time. Ancient as I am at sixty-nine, withered and broken in my modest rooms at Kecharitomene, I find that not an hour passes without my mind turning to the events chronicled in that book of mine. And not for the reasons one might suppose. The historian, as I wrote therein, must shirk neither remonstrance with his friends, nor praise of his enemies; he is in the service only of Truth. And this, more than anything, is what gnaws at me now. While I did not bear false witness, nor did I tell the full story. Much was left unsaid or unremarked upon, much ignored in order not to bestow credit upon some heroic character other than my father. The women, especially, I have marginalized: my irrepressible grandmother and namesake Anna Dalassene, the formidable Empress Eudokia Makrembolitissa, and most of all the lovely Maria of Alania, who was so forthcoming in relating to me the momentous events of her incredible life. These egregious omissions fill me with shame. Of all people, I should have known not to downplay the female contributions to our proud history!

It is Candlemas Day, Anno Domini 1153. John II Komnenos, my hapless half-brother and my father’s unworthy successor, is sixteen years dead. His flouncing son Manuel now occupies the throne. My throne. Or, rather, the throne that would have been mine were I not of the weaker sex. The throne that should have been mine regardless.

I, Anna Komnene, Lost Queen of the Byzantines.

Men cannot know the anguish of being ruled ineligible on anatomical grounds beyond one’s control. Slaves can perhaps understand, eunuchs too, and perhaps even those doomed nobles, like the deposed Emperor Romanos Diogenes, whose eyes have been put out. But not men! How apposite is the Scripture, Adam content in his slothful ignorance, lazy ruler of all he surveys; Eve ripe with fecund curiosity and grand ambition; Eve punished for the selfsame willful attributes gifted her by her Creator.

The cruel vicissitudes of fate, of which the tragedians sang so plangently: my tale is worthy of Aeschylus or Sophocles. I will not lie, it is a struggle to avoid bitterness. Tragedies often end in death, as a cursory survey of Greek drama shows, but death at least is respite from bitterness and rage and humiliation. Real tragedy is confinement to a convent, house arrest in this forgotten place, exile to irrelevancy. The blind Oedipus (or Diogenes!) wandering the earth. Impotence, celibacy, boredom. Intellectual stagnation. Rot.

The machine of government grinds on without me, entombed as I am in this mausoleum-by-another-name. My nephew, traipsing ‘round the Grand Palace in those ridiculous pantaloons, entertains infidels, but will not grant his aunt an audience. My own children scorn me. My friends—there were never, let us be true, very many—have all passed on.

I have managed the best I could. When my husband died a dozen-and-a-half years ago, he left behind fragments of a manuscript, a history he’d intended to continue to the present day, or at least through the reign of Alexios that ended in Anno Domini 1118. I picked up where he left off—although his scholarship was too shoddy to be of much use. My helpmate was more Hannibal than Plutarch. By completing Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger’s history of Alexios Komnenos, I could honor both my husband and my father. This was the well-intended advice the Mother Abbess put before me: “Serve the memory of the two distinguished men who were your masters,” she said. And so I did, to a degree that even my kindly Mother Abbess scarce could have imagined. The Alexiad not only far exceeds the immature scribblings of my husband, but ranks, dare I say, with the works of Herodotus and Xenophon. Certainly the blundering Psellos is not my match, as he could never resist the temptation (as I have, although I have more reason to include myself than that old fraud!) to insert himself so prominently in every relevant scene. So long as the Alexiad exists, Alexios Komnenos and Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger will never be forgotten. No daughter or wife has ever given greater glory to father and husband!

Selflessly have I acted in composing my history, but History is not well served by selflessness. Mea culpa, I have presented a flawed account. O History, I have betrayed thee!—just as I was myself betrayed by my father, by my husband, by my very anatomy. “The reward of suffering is experience,” the playwright wrote. But he has it wrong, it’s the other way around: the reward of experience is suffering. The guilt of my literary deceit weighs heavily on me. I lie awake at night. Beneath the habit, what little hair that remains falls out in clumps.

If the truth is ever to be told, I am the only one left to tell it, and tell it I must. I must atone for the sin of redaction, a sin for which neither presbyter nor Patriarch can offer true absolution.

Let these pages be my penance, O God.

I. The Astrologer

At half past ten in the morning, on the first day of the twelfth month of the Year of Our Lord 1083, a eunuch burst out of the Porphyra and hurried into the nearby chambers of the court astrologer, an Antiochene by birth, who had served the emperors of Rome since the days of Monomachos. The astrologer was at his writing desk, ephemerides at the ready, awaiting the eunuch’s arrival.

“What was the time?”

“Just now, sirrah.”

The astrologer nodded, ran his silt-brown fingers through his thick white beard, and turned to his books: that year’s ephemeris first, then the well-worn copy of Claudius Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos. As he made his notations, a crooked smile broke across his grizzled brown face. After ten minutes of furious computation, he put down his pen and exclaimed “But God is good” to no one in particular, as the dutiful eunuch had already returned to the Porphyra to attend to the new mother and her baby. The old man rose and practically ran down the hall to the royal apartments, dizzy with excitement.

He found the Emperor in the Map Room, anxiously pacing to and fro, wearing holes in the rugs.

“What news?” the Augustus cried.

“The child is born,” the old man said. “And Your Excellency, the stars are a thing of wonder!” He went on to analyze the natal chart of the Emperor’s first-born and heir to the throne. “The position of Mars in the first house, so close to the horizon…Your Grace, you could not ask for better placement.” Mars, the astrologer explained—although the Emperor was himself familiar with Ptolemy, and did not require remedial instruction—was ruler of war, and thus its position on the Ascendant indicated an assertive, self-confident aspect well-suited to command. This child was a natural-born leader, the sort of man others would happily follow into battle, even into certain death. “Not unlike yourself,” he added, in a tone of well-practiced obsequity. (He had not retained his position for so long without knowing how and when to deploy blandishments). The Emperor nodded, and the old sycophant continued: “And Jupiter, also so close to the horizon…Jupiter is the Great Benefic. This is a lucky child, Your Grace. Lucky indeed.”

“This pleases me,” the Emperor said. “Thank you, sirrah. That is all.”

The astrologer was banished to Proti the very next day, after the Emperor discovered—to his eternal disappointment, given the auspicious astrological reading—that the baby crying in the Porphyra, his first-born child and presumptive heir, was in fact a girl.

The Emperor was Alexios Komnenos.

The baby girl was me.

I am in love with your book. I listened at the end of the pod - twice! Absolutely riveting!

While I will definitely be ordering an actual book, allow me to offer a plea from the visually impaired community (raises hand), please finish the audio book. 😀

Cheers! 🥂

My book order will arrive later today. I can't wait to start reading it! I wish I knew earlier there'd be a unique package with a signed copy and the coin. I'm so glad you are coming back to novel/fiction. Allison's narration is captivating. I'm sure the audiobook would be a hit, too. Congratulations on your new publication, Greg!