Dear Reader,

Hemingway at some Parisian bistro; Dorothy Parker at the Algonquin Round Table; Lawrence Durrell and friends in Alexandria; Lord Byron and Claire Clairmont, Percy and Mary Shelley on the Geneva writer’s retreat that spawned Frankenstein: There is a long list of writers I would love to go back in time and hang out with.

Henrik Ibsen is not one of these writers. He was indubitably a great playwright, but he was not a good time. With his muttonchops, top hat, and cane, he looked like a character out of Dickens—specifically, a parsimonious hard-ass who might have dined at the club with Ebenezer Scrooge and Harold Skimpole. From what I gather, he was an arrogant, condescending, manipulative control freak, and such a know-it-all that his dying words—spat at his poor hospice nurse, who had assured a visitor that he was on the mend—were “Tvertimod!”: “On the contrary!”

Like his native Norway in wintertime, Ibsen is dark. One does not go to a production of A Doll’s House or The Wild Duck anticipating raucous laughter, or mirth, or restoration in one’s faith in the essential goodness of human nature. Usually there is a family of means and influence that looks perfectly normal on the outside, but on the inside some dreaded secret is hiding, and by the end of the play the secret is revealed, and the family breaks apart, and at least one person is dead, and everyone is worse off than when the curtain rose, and you stagger out of the theater feeling like you’ve just escaped two hours of peine forte et dure.

His plays are heavy.

At least, that is my memory of Ibsen’s work. I read most of this stuff in high school. And this is not to suggest that the plays are subpar. Tvertimod, they are fantastic. Spanning a full half-century, from 1850’s Catiline to When We Dead Awaken in 1899, Ibsen’s plays feature strong female characters (not a thing in the Victorian era) and tackle complex issues (women’s rights, the intersection of high social status and dwindling finances, weird and sometimes incestuous family dynamics, substance abuse, etc.). He was a keen observer of human nature who reimagined theater as depicting real life. There is a reason James Joyce taught himself Dano-Norwegian so he could read Ibsen in the original.

In 2001, I saw Kate Burton in Hedda Gabler on Broadway—an exquisite actress in a role famous for its Hamlet-like complexity. Even better was a production of Ghosts at the Shakespeare Theater in New Jersey 30-some-odd years ago. I don’t recall all the details, but I remember being blown away when the title was realized, after we had watched a recovering alcoholic ruin his life’s work because he relapsed.

I’ve had Ibsen on the brain ever since Donald Trump unknowingly quoted the title of one of his plays a few weeks ago: the media, Orange Grover Cleveland said, was the “enemy of the people.” This was somewhat ironic, as Trump is a walking, talking amalgamation of all the character traits Ibsen most despised. But I decided to revisit the play after the election, for reasons I’ll explain shortly.

My playwrighting professor in college, the great Donn B. Murphy, taught us that when writing a play, start with a question you didn’t know the answer to: what would happen if X did Y? Drama would come out of us trying to determine the solution. Enemy of the People—the more alliterative and succinct En Folkefiende in Dano-Norweigian—seems like it was written using this prompt:

There is a town in Norway, home to a profitable tannery, that has become famous for its spas. Thus, the local economy is driven by tourism. But a prominent doctor, Thomas Stockmann, discovers that the water is contaminated with bacteria. He decides he needs to alert the townspeople to this imminent danger, and makes plans to publish his findings in the local newspaper.

The mayor of the town—who is also, by some quirk of fate, and because so much political power in 19th century Norway was concentrated in the hands of very few families, the doctor’s brother—gets wind of this and tries to get Stockmann to keep quiet about the discovery, not wanting to scare off all the tourists. (It won’t surprise you to learn that Jaws was partly inspired by Ibsen’s play; the Steven Spielberg blockbuster is basically Enemy of the People with sharks.)

Further complicating matters, the water is contaminated because of toxic sludge flowing to the spas from the tannery, which is owned by Morten Kiil, who is both Stockmann’s father-in-law and the wealthiest burgher in town. Kiil is in no big hurry for everyone to learn that he’s the one responsible for ruining the town’s tourist industry. Meanwhile, the editor and the publisher of the newspaper have second thoughts about whether or not printing the article is such a bright idea; will it do more harm than good? Can’t Stockmann just treat the water on the Q-T, without making a federal case of it?

The titular “enemy of the people” is neither the rich industrialist Morten Kiil, nor the corrupt mayor, nor—contrary to Trump’s assertion—the editor and publisher of the newspaper. No, the Folkefiende is Dr. Stockmann, who inspires the wrath of everyone in town because how dare he try to alert people to the imminent dangers of tainted water. (Enemy of the People could also be called Kill the Messenger.) In the play’s climactic fourth act, which takes place at an emergency town meeting, Dr. Stockmann takes a stand against the establishment, and, um, things don’t go so well. Each for his own reasons, the townspeople would rather do nothing, and chance the contaminated water poisoning them and their tourists, than take any sort of decisive action beyond shouting at the one guy trying to keep them safe.

Reading the words on the page back in high school, that outcome seemed to me implausible. Why would people willingly, angrily lobby for their own death and destruction? But we need only transpose the action to the pandemic of 2020 to understand that Ibsen was spot-on. There is nothing rational about how the American public treated Dr. Fauci, who committed the grievous crime of asking people to trust the experts and modify their behavior ever so slightly to save lives.

I’m not the only one who sees Fauci in Stockmann, and our entire current predicament in Ibsen’s play. Amy Herzog’s adaptation of Enemy of the People was staged in New York earlier this year, with Jeremy Strong as Dr. Stockmann and Michael Imperioli as his brother. As Jesse Green wrote in his New York Times review:

It’s too weak to say that this conspiracy of inaction makes “An Enemy of the People” relevant; its issues and ours are not similar but identical. And not just its issues. Its characters, too, are contemporary: doppelgängers of our own vicious demagogues, cowed editors, greasy both-sides-ists and defanged idealists. More than once, I thought Strong must have modeled his spectacularly accurate yet non-showy performance on Dr. Anthony Fauci, the embattled former infectious disease expert, including not just his messianic faith in science but also his barely mastered disdain, social weirdness and haircut.

But what inspired me to revisit Enemy of the People, as I mentioned, was the result of the election. How could Trump, this obvious monster, have won the popular vote? How? Like, seriously, WTF?

And then I remembered this pivotal exchange, where Stockmann takes on various antagonists at the town meeting (Note: like Arthur Miller and Amy Herzog before me, I’m tweaking the translation a bit):

DR STOCKMANN: Oh, I’ll name them all right, don’t you worry! Because that’s the discovery that I made yesterday. The most pernicious enemy of truth and freedom is the majority. Yes indeed, that damned, compact, liberal majority—that is the real enemy.

ASLAKSEN: The chairman asks the speaker to retract his offensive remarks.

DR STOCKMANN: Not in a million years, Mr Aslaksen. It is the majority in our society that robs me of my freedom and would forbid me to speak the truth.

HOVSTAD: The majority always has the right on its side.

BILLING: And so has truth, by God!

DR STOCKMANN: The majority never has the right on its side. Never! That’s one of those societal lies that intelligent, free-thinking men must reject. I ask you: Who is it that forms the majority of the population in a country? The smart people, or the stupid people? I think we can agree that stupid people are in the overwhelming majority all over the world. But, damn it all, surely it can never, ever be right that the smart should bow down to the stupid!

(The people try and shout him down.)

DR STOCKMANN: Sure, sure—you can shout me down, I know. You can cut off my mic. But you cannot prove me wrong. The majority has might on its side—unfortunately; but right it has not. I am in the right—me and a few other scattered individuals. The minority is always in the right.

In short: the majority of the people are always wrong, because the majority of the people are stupid.

I enjoyed this passage tremendously in high school, because I felt like it gave me license to be an elitist jerk. But now I see that Dr. Stockmann isn’t correct. Reality is not so absolute. The majority is right plenty of times. Not in the case of the 2024 election, obviously, but more often than not.

What’s fascinating about Ibsen is that, like Orwell, he’s one of those iconoclastic writers whom left and right try to claim ownership of. Consider: Dr. Stockmann grows more angry and bitter as the play goes along. His proclamation at the end that “the strongest man in the world is he who stands alone” is the kind of Don’t Tread On Me sentiment rightwing influencers hold dear. That Enemy of the People was written as a thinly-veiled response to critics who didn’t like Ghosts, his previous play, is a very MAGA thing to do. This exhortation:

Aren’t they denouncing as lies everything I know to be true? But the craziest thing of all is that here we have hordes of liberal adult individuals going around telling themselves and others how open-minded they are!

may as well be a rant against wokeism and cancel culture. Is it hard to imagine a modern-day Dr. Stockmann leaving Norway (as Ibsen did), and doing guest spots on Steve Bannon’s podcast (as Ibsen did not do)? There are passages in that fourth act, after all, where Stockmann trots out eugenics to drive home his most-people-are-dumb argument.

Originally motivated by the truth, and by science, and by medical ethics, Stockmann by the end of the play is, like MAGA, animated by grievance. Lumping most of humankind under a single banner—“They’re all liars!” “They’re all morons!” “They’re all hypocrites!” or what have you—is a way of dissociating, after all. Obdurate inflexibility is, ultimately, antisocial behavior.

Here is another timely passage, for those of us struggling to understand what happened on Election Day:

DR STOCKMANN: What does it matter if a lying society is destroyed? It ought to be razed to the ground! Exterminated like termites, that’s what they ought to be, all those who live a lie! You’ll end up contaminating the whole land; you’ll bring it to the point where the whole country will deserve to die. And if things go that far, then I say, from the very bottom of my heart: let it all be laid to waste; let the whole country die off!

A MAN (in the crowd): Those are the words of an enemy of the people!

BILLING: There it is—the voice of the people!

THE WHOLE CROWD (yelling): Yes, yes, yes! He’s an enemy of the people! He hates his country! He hates the entire nation!

I know that I’ve said words lately to the effect of: “If we elect Trump again, and Biden and the Democrats surrender without a fight, maybe the United States doesn’t deserve to continue.” Does this mean that I hate my country? Or that I love it?

In his review, Green describes Enemy of the People as “a bitter satire of local politics that soon reveals itself as a slow-boil tragedy of human complacency.” Complacency is the state of mind I find myself gravitating towards the most in these post-election days, but one I can least afford. Complacency is surrender; therefore, complacency is complicity. Freedom and truth have to be defended—especially when the enemies are fascists!—and are worth fighting for.

And with that in mind, as we gird up for the long struggle ahead of us, I leave you with this sage piece of advice from Dr. Stockmann: “You should never wear your best trousers when you go out to fight for freedom and truth.”

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Lisa Graves, executive director of True North Research:

I have been active on BlueSky for a year and a half. This week, there’s been an enormous spike in new users, which is wonderful. If I’m not following you there, please email me with your handle and I will do so.

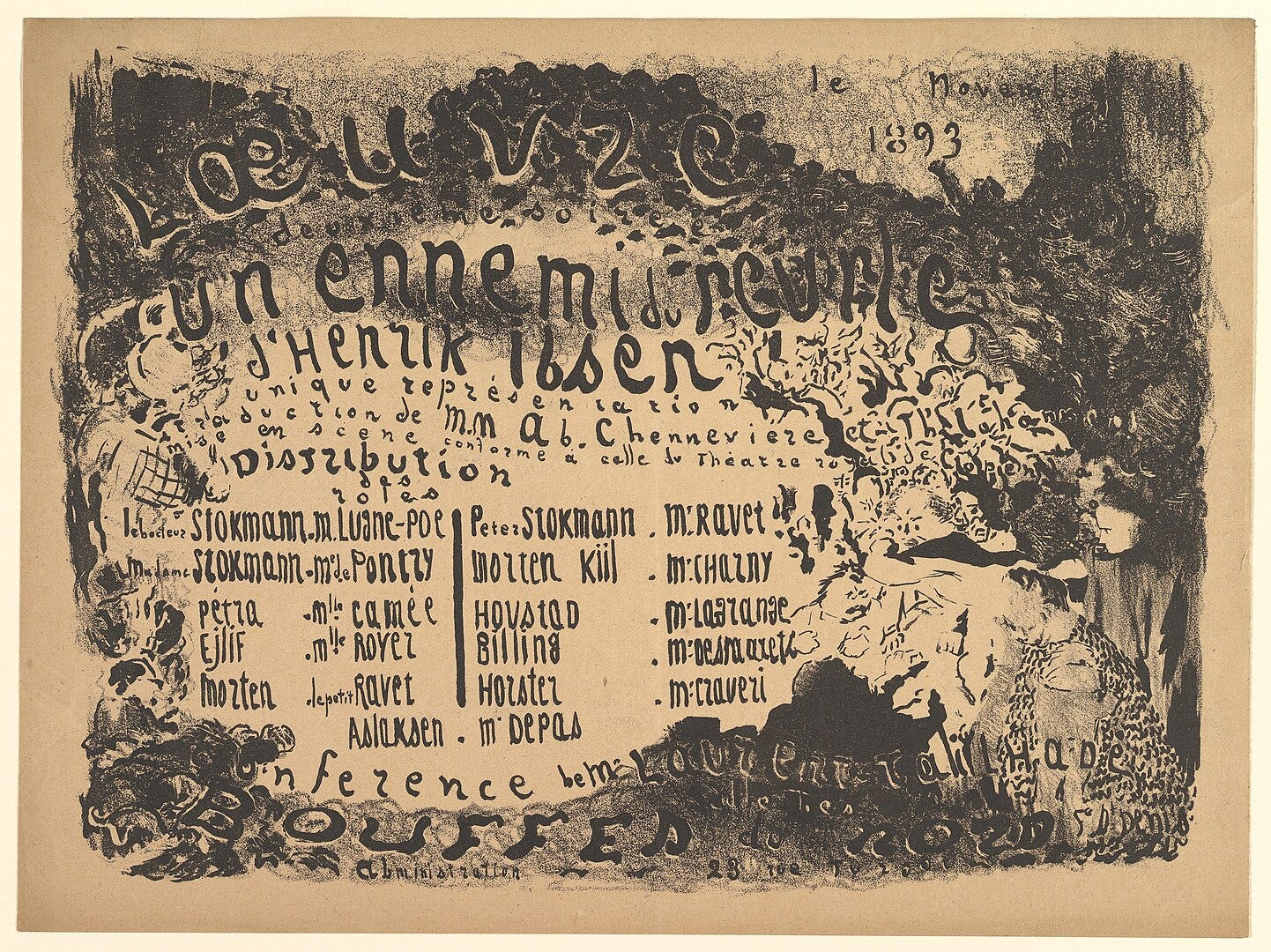

Photo credit: Édouard Vuillard, An Enemy of the People program for Théâtre de l'Œuvre, November 1893.

I am truly lucky I get to read the news from a historical perspective (Heather Cox Richardson) and from a literary one, too. I may be one of the dumb ones but you're making me smarter, Greg. Gracias!

Thanks for the perspective, I always learn something. I have frequently thought about this very play, which I saw at least 40 years ago, in the context of the election, and those very lines, where, I think, Stockman says something to the effect that "it takes 20 years for the public to be right about anything." Often it is longer.