Dear Reader,

This week, as the artless King Donald usurps the leadership of the Kennedy Center for the Arts, replacing its board members with a philistine confederacy of MAGA dunces—and as I still reel from the visceral shock to the system generated by the abject awfulness of the AI Super Bowl ads—I find myself contemplating the question: What is art?

On our honeymoon in 2002, we went to see the Eiffel Tower, mostly because we were in Paris, and one simply cannot visit Paris, especially on one’s honeymoon, without taking in the city’s most famous, and most romantic, tourist attraction. Expectations were low. We were jaded New Yorkers, after all. I walked past the Empire State Building every day on my way to work and barely looked up. I did not expect the Tower to move me in any way. But move me it did—and not just because of the gusts of wind blowing through my hair, swaying the giant metal edifice. What I did not understand about the Eiffel Tower until I stood in front of it, what no photograph could adequately convey, is that it is not really a Tower at all, but a thousand-foot-tall work of art.

When it was constructed in 1889, for the Paris Exposition to commemorate the centennial of the French Revolution, the Tower was the source of rigorous and ardent debate among art critics, professional and amateur alike. Those of a more conservative bent loathed the thing, considered it an eyesore, out of place among the Haussmann renovations of 1853-70 and the great medieval cathedral of Nôtre Dame. Those of a more open mind were enthralled by it. Competing attitudes towards the Tower animated the subsequent Surrealist movement, as Nahma Sandrow explains in 1972’s Surrealism: Theater, Arts, Ideas:

After all, it had become obvious by now that unlike what the Haussmann boulevards had been, the Tower was not part of a dynamic, politically powerful France; it was not a continuation of a wave of construction of which the boulevards had been an early product; rather, it was a monument to a technology which was building very little, and to a France overpowered twice in fifty years. The irony of the Exposition for which the Tower was built now began to surface: the Exposition honored the future by commemorating the past: the French Revolution. And an extra absurdity lay in the fact that the Revolution itself further retarded possible industrialization by splitting and rigidifying social classes. Besides, the Tower was almost useless. How then could intelligent people look up (except literally) to the Tower?

Attitudes were changing, and the way the Surrealists dealt with the Tower is a clue. This young group adopted the Eiffel Tower not as a symbol of dynamic technology but as a technological pet. They painted pictures of the Tower for the fun of it—and for the fun of being heretical. Indeed the very fact that the Tower had begun by affronting conservatives further endeared it to the Surrealists, who were pleased to carry on the precedent by affronting their own now-conservative contemporaries by their unorthodox reactions. The Tower was a monumental rude gesture.

The reason for this evolution of opinion, as Sandrow points out, is that the Surrealists came a generation later and had never known a Paris sans Tower. To them, it had always been there. Some of what makes art art is context—or, to put it another way: art is concerned with time. This is an idea that Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) grappled with: art being not just visual (“retinal,” as he called it), but incorporating all five senses, and also being active, and thus existing in the moment: interacting with time.

I’m hard-pressed to think of anyone more qualified to answer the “what is art” question than Marcel Duchamp. As a general rule, he spent a lot more time grappling with ideas about art than actually making art. (Curiously, the word “art” appears just twice in André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto, both times in passing, so we can’t look for a definition there.) As his contemporary and fellow Dadaist Pierre de Massot wrote, “Duchamp never stops thinking and, thinking, never stops creating.” The art critic Sarane Alexandrian categorizes him as “neither a painter, a sculptor, a poet, nor writer; he was someone rather than no one.” Duchamp fervently believed, Alexandrian writes, “that what an artist did not do is just as important as what he did.”

And what he did not do was a lot. Talented beyond measure, but unwilling to commit to any one medium, form, format, school, or style for longer than it took him to absorb its artistic lessons, he would paint in a particular manner, get bored, and move on to the next thing. Duchamp was the epitome of the avant-garde. He was involved with a series of modern artistic movements—Postimpressionist, Cubist, Futurist, Dadaist, Surrealist, Kinetic. If modern art was yacht rock, he would be Donald Fagan. The whole scene radiated from him.

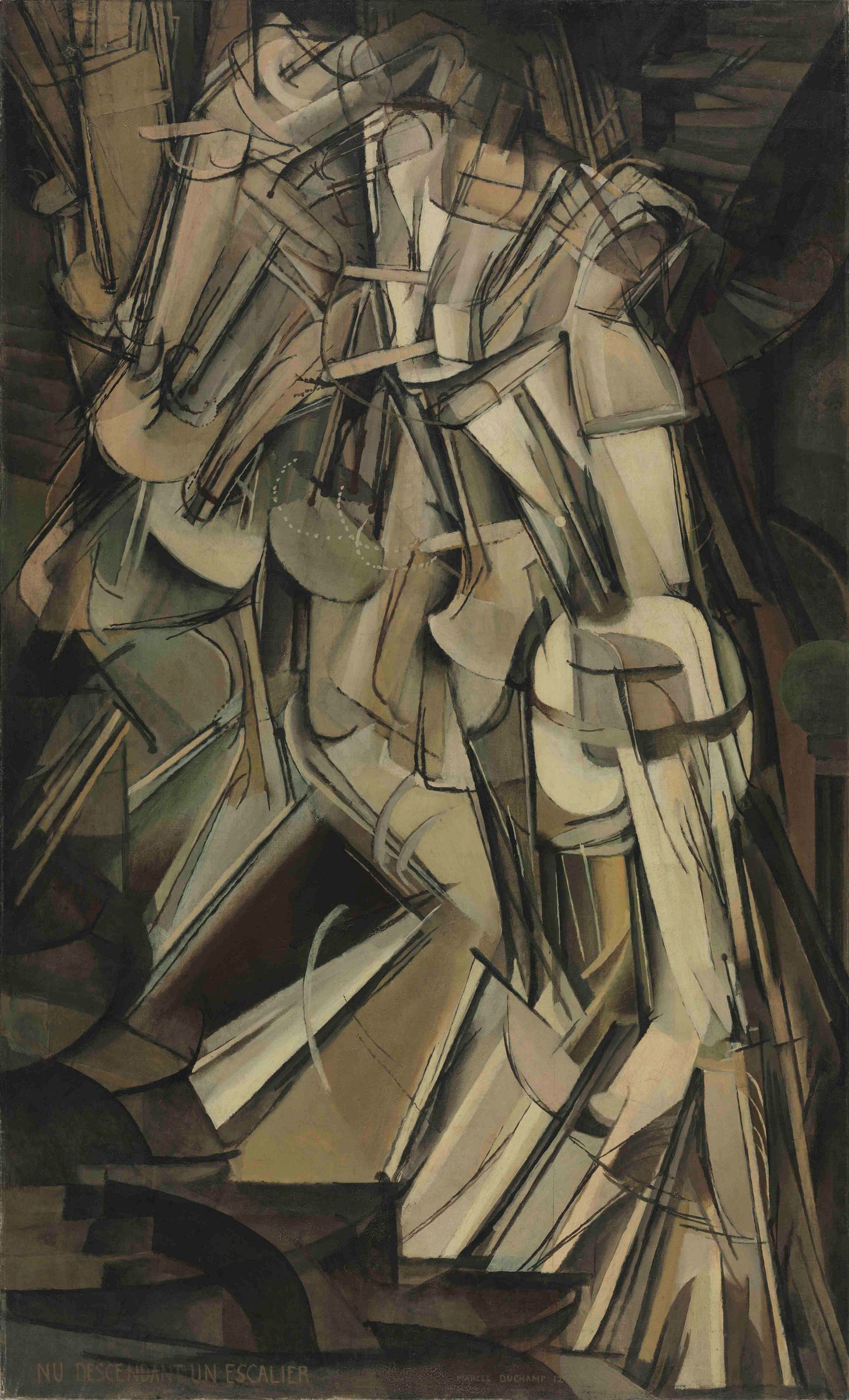

He was frustrating to collectors who wanted more output. After achieving international fame in 1912 with his Modernist classic Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2—considered risqué at the time, but objectively about as erotic as a drawer of silverware—Duchamp could have locked himself away in the studio and banged out a few dozen more Nudes Descending Staircases to line his pocketbook. But he didn’t. Ever. Insofar as it was possible, he tried to keep money and art separate. He lived the old MGM slogan “ars gratia artis”—which is itself not an old Latin expression at all, but a modern invention lifted from the French credo “l’art pour l’art.”

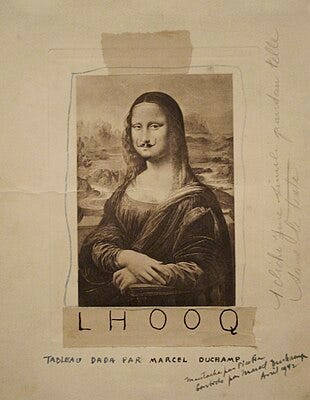

Duchamp is one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, but if I ever laid eyes on Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 before yesterday, it made no impression on me. His most recognizable work is probably—I shit you not—a generic print of the Mona Lisa on which he cheekily scrawled a mustache and goatee:

This was called L.H.O.O.Q., five letters that, if spoken out loud, are pronounced “Elle a chaud au cul,” which is French slang for “She has a hot ass”—or, in Duchamp’s own translation, “She has a fire down below.” While not much to look at, L.H.O.O.Q. is subversive, naughty, edgy, provocative—what we might today call “punk rock.” It’s also a subtle commentary on the Mona Lisa itself, on its vaunted place in the world of art history, and on Leonardo da Vinci’s sublimated sexual preferences.

Duchamp “retouched” that print in 1919, more than a hundred years ago, but his modification of the da Vinci seems to anticipate our current gender-fluid era. A few years later, he created an alter ego, Rrose Sélavy—in French, “Eros, c’est la vie”—who appeared in a series of photographs, taken by his good friend Man Ray, of Duchamp in drag. That was in 1921!

Even as an old man, Duchamp was ahead of his time. His “will,” a piece of art he slaved over for two decades in his Greenwich Village apartment in total secrecy, was made to be broken down and moved around. The assemblage consists of a medieval-looking wooden door—maybe to a crypt, maybe to a catacombs—and when you look through the two peepholes, you see the actual painting: a naked woman, her head not visible, splayed out on some brush, holding a gas lamp, against the backdrop of a sensuous waterfall landscape. Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas looks like none of his previous work, not even remotely, while also somehow being a synthesis of all of it. The painting is weird and provocative, but also unmistakably, unimpeachably cool. It could be the cover of a lost Led Zeppelin album, or a still shot from some NC-17 version of The Lord of the Rings.

What does it mean? Your guess is as good as mine. As a young man, Duchamp was rejected from an art competition because a judge thought his female nude was inadequate; after this initial humiliation, he kept returning throughout his life to the problem of how best to capture the nude form. Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas is, I think, his final answer to the question. The “illuminating glass” indicates that he’s seen the light. The backdrop is hauntingly beautiful. And while the nude woman, disturbingly naked and in such an odd pose, has provoked all manner of emotional responses in spectators—not all of them positive—to me, she symbolizes willful surrender: to the mystery, to the process, to ineffability, to the acceptance of not knowing.

As Alexandrian writes: “Duchamp’s motto, which went beyond the ‘What do I know?’ of Montaigne, is…: ‘Perhaps nothing.’ Where one believes that there may be something, perhaps there is nothing; and where one believes that there may be nothing, there may be everything.”

In 1941, after the Nazi occupation of France, Duchamp managed to make his way through his native country by posing as a traveling cheese salesman(!). A year later he was back in New York, and he would remain based in the United States until his death. Even during the Second World War, his focus remained on art. As Alexandrian writes, Duchamp sought “to proclaim that in spite of the war, the life of the spirit, with its protest against sordidness and its hope [for] the wondrous side of life, continued.”

The failed Austrian artist in Berlin could not destroy the true French artist in New York. There is a lesson there.

Duchamp pioneered what he called “readymades,” which are basically objects that he found lying around, ever-so-slightly tweaked, and consecrated as Art. In New York in 1917, he famously ordered from a plumbing supply company a porcelain urinal. Reorienting the piece 90 degrees, he scrawled “R. Mott 1917” on it, gave it the title Fountain, and entered it into an exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists under a pseudonym (although everyone suspected it was his creation). This was at the height of the Dada phase. The curators were not allowed to reject the thing, but they didn’t much care for it—it was a urinal, after all, although thankfully a new one—so they hid it in the gallery.

Later, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz published a picture of the piece in an art magazine, The Blind Man, which provoked all manner of responses. Something like Fountain welcomes if not demands diverse interpretations. My guess is that most people who saw the readymade responded with a simple, dismissive question: “How is that art?”

But it is. With Duchamp, it always is.

Pretend you don’t know its intended function and look at Fountain closely: it is beautiful. There is elegance in its lines. The bowling-pin layout of the drain holes is visually appealing. Even in the photograph, we can see that the shiny porcelain glistens in the light; it illuminates. The hole at the bottom does look like a fountain. The signature is a reference to Mutt of “Mutt and Jeff,” at the time a popular comic strip; the R. stands for Richard; taken together, this was a dig at bloated plutocrats who buy art as investment. Fountain asks us to think about the arbitrariness of what we choose to put on a pedestal. And, finally, because it is so audacious, the piece, ha ha, pissed a lot of people off.

As Alexandrian writes, Duchamp “posed to artists, if not the general public, the question: What is a work of art? Could one create a work which was not art or practice art without creating a work? . . . [T]he fact that [he] had not made this ‘fountain’ with his own hands was irrelevant; he had selected it.” The artist’s choice to elevate a urinal to the status of art was sufficient to do so. “He had taken an everyday, commonplace object and treated it in such a way that its normal meaning had given way to another one, which was exclusively intellectual. . . The urinal was an impertinent method of letting artists understand that a scorned utilitarian object was of more value than a canvas daubed without wit or originality.” Thus Fountain was itself both a work of art and a critique of Art.

(Duchamp’s own final words on the matter were less philosophical: “The only works of art which America has contributed to society are its plumbing equipment and its bridges.” In his defense, he wrote that long before yacht rock.)

Contrast Duchamp’s “fountain” with Donald Trump’s famous gilded toilet bowl. Doubtless the golden commode in the tacky Fifth Avenue penthouse is “nicer” than the utilitarian Great War-era pissotière. But it ain’t art. All it is is a fancy receptacle for a bullshitter’s shit.

Through some mysterious creative alchemy, a bona fide artist like Marcel Duchamp can elevate a urinal—a urinal!—into a work of art.

A rough beast like Donald Trump, meanwhile, can’t help but reduce the Kennedy Center of the Arts to nothing more than a place to pee.

ICYMI

The brilliant and always hopeful Lisa Graves returned to The Five 8:

A NEW YORK EVENT!

On Monday, February 24, it is my great honor to participate in a discussion with retired Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman about his new book, The Folly of Realism: How the West Deceived Itself About Russia and Betrayed Ukraine. If you’re in the city, please come to the event, which will be held at the lovely Ukrainian Institute of America.

(That photo of me is from my French book tour in 2011, before my hair went gray.)

Finally, thanks for purchasing my new book of essays, The Age of Unreality—an Amazon #1 New Release. You can buy it not from Amazon here.

Hi Greg. What a sadness hangs now over the Kennedy Center. If the Eiffel Tower was standing near the Texas southern border, Trump would scrap it to help build a wall. I pray that someday we are not discussing the Trump Center. How fitting is the Duchamp urinal when discussing Trump Fuckery. Great writing.

As always, your essay is a work of art. We never know what to expect. Billserle.com