Dear Reader,

Today I saw a bird that was bright orange. I have no idea what kind of bird this is, and I’ve never seen it before. It was high in a tree, chirping along with my beloved red-winged blackbirds, which have also returned. Spring is here, Republican traitors are as obvious as that orange bird with their pro-Putin exhortations, the vaccines are coming—and this week, I saw one of the all-time great newspaper headlines: “San Antonio Wax Museum Removes Trump Figure Because Visitors Kept Punching It.”

San Antonio, guys. Texas! No wonder Ted Cruz is desperate.

What a difference a year makes.

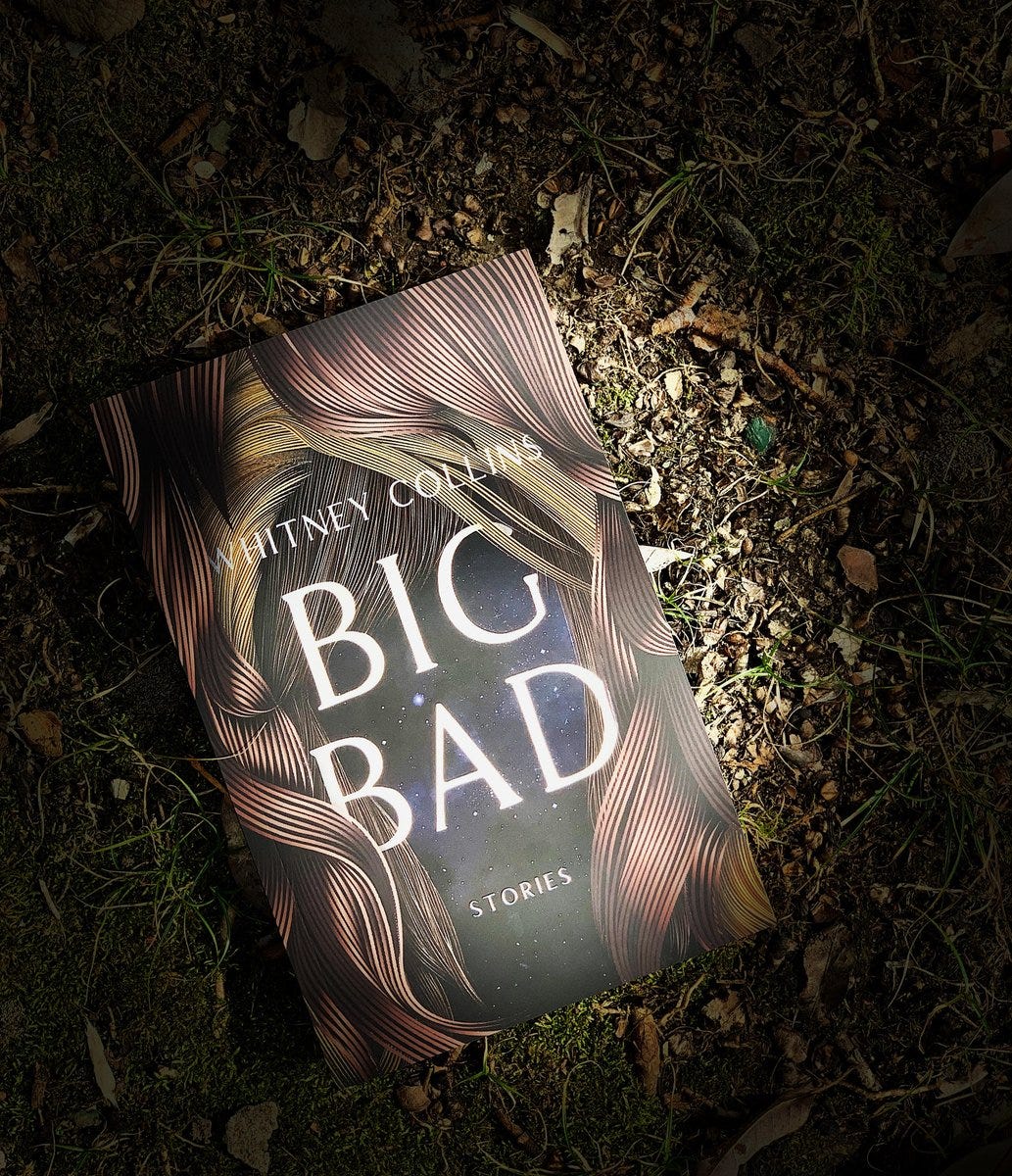

Today’s “Sunday Pages” is a short story by my friend, the very funny Whitney Collins, from her sparkling new Mary McCarthy Prize-winning collection, Big Bad. This one has really stayed with me, as the best literature always does…

Good Guys

To be fair, the kid was asking for it. The moment he stumbled into Holbrook College’s cooperative dorm with his archaic set of yam-colored suitcases and big Midwestern smile, he might as well have passed around engraved invitations to his own ass-kicking. He arrived at the Collective during a rowdy dinner of wine and lentil loaf, and as he stood grinning in the dining room doorway, the late August sun made a nimbus of his prairie-colored hair.

“Hello folks!” he said, breathless with innocence. “I’m Leonard Salts from Illinois. You can call me Leonard or Lee or Leo or Leon—whatever floats your boat.”

Leonard’s earnestness was palpable. It brought all forty Collectives—their banter and scraping of tin plates—to a hush.

“Looks like I got the last room on campus, but I figure that’s what happens when you can’t make up your mind between New Hampshire and Ohio.” Leonard shook his head like he was an utter fool. “Ohio, New Hampshire. New Hampshire, Ohio. Finally, I just looked in the bathroom mirror and said to myself, ‘Leonard, you nut! You bona fide coconut! Ohio? You know Ohio. It’s just like Illinois but with less corn and more porn.’” The kid lowered his voice like he was letting everyone in on a family secret. “At least that’s what my dad, Walter Salts, says. I know, I know. Walter Salts, Walter Salts. My grandmother was a poet and she didn’t even know it. Or maybe, just maybe, she did.”

Leonard gave a little snort and addressed his suitcases. Two were tucked under his arms and two he held by their silver handles. Like a bellhop, he stacked them in a pile on the dining room floor from biggest to smallest. On top was a squat and square ladies’ cosmetic case that the whole room seemed to consider at once. Leonard, unburdened, went on. “But, back to the why and how. In the end, New Hampshire picked me and I picked New Hampshire and the administration picked this place for me to live. Well, not picked actually, because it was the only room left. But here I am and nice to meet you all. Again: Leonard Salts from Ursula, Illinois. Probably never heard of it, but now you have and you can no longer say you haven’t.”

Leonard gave a little bow. There was a quiet chortle or two, followed by a low whistle from the rear of the room. It seemed for a moment that no one knew what to say. The Collectives in their designer love beads and imported leather sandals looked at one another, this way and that, as if they were being pranked and one of them was responsible. At long last, Teddy Yates, the Collective’s president, stood and lifted his coffee mug of wine.

“Well, I say welcome!” Teddy’s voice took on the showman’s tone that his dorm mates had come to expect, a tone Leonard mistook as genuine. “The Collective is exactly that: a collection of all sorts and all types. I think you’ll find yourself right at home here. In fact, ten minutes from now, I bet you the farm you won’t miss Nebraska at all.”

Leonard’s smile fell a bit. He corrected Teddy with an “Illinois,” but his state of origin went unheard in the roar of applause for Teddy. The next thing Leonard knew, he was being pushed down into a dining chair and up to a table where someone slid him a tin plate of lentil loaf and a full mug of wine. Leonard, in the chaos, tried to insist he could partake of neither—one because of his weak stomach, the other because of his morals—but the Collectives collectively pouted as if the whole bunch of them might burst into tears, and after much cheering and jeering, Leonard choked down what was in front of him before promptly regurgitating all of it back onto the table. The applause that followed was so deafening and lengthy, that Leonard, pale and clammy, eventually gave a weak smile in spite of himself. Then Teddy yanked him up by the armpits and clapped him on the back and showed him to his third-floor room.

“Welcome home, Nebraska,” Teddy said, gesturing at the concrete walls and iron bed. “You’re not in Kansas anymore.”

Leonard opened his mouth and closed it. “Right,” he said meekly. “Thanks.”

Teddy wasn’t sure why he started in on Leonard, but he felt compelled to. When he woke the next day and saw Leonard sitting in the dining room with a tall glass of milk, he recalled a horse he’d once seen broken. Teddy’s sister had once been into the equestrian world out on Long Island, and one summer Teddy had tagged along to see how people went about training a show horse. A woman had put a rust-colored horse with flared nostrils on a long leash and trotted it in a circle for a good hour. First clockwise and then counterclockwise. The woman explained to Teddy and his sister that she held a whip, just in case, but she rarely needed to use it. She maintained that repetition was stronger than violence, and Teddy remembered this as he watched Leonard take a long pull from his milk and forget to wipe his upper lip. Teddy could see it clearly; the world would devour Leonard if someone didn’t show him the ropes, so Teddy decided that a few times a day, he’d take it upon himself to get out the ropes and dangle them in front of Leonard’s angelic corn-fed face. Never mind if this behavior wasn’t in keeping with the Collective’s original mission of love and let love, live and let live. It was for Leonard’s own good.

For the first week or so, it was just “Nebraska” whenever Teddy saw Leonard. “Missing Nebraska?” he might say, or: “This is my new buddy Leonard. He’s from Nebraska.”

Leonard would always reply, smiling. “Well … actually. It’s Illinois. Ursula, Illinois.” To which Teddy would give his head a big oafish shake or tap his temple and say: “Geez! Silly me! That’s right! Illinois!” only to repeat the “Nebraska” trick a few hours later. When, after about ten days, Leonard quit smiling and quit correcting Teddy about Nebraska, Teddy made fast to re-win Leonard’s affection so the training could continue. “Hey, Peoria!” Teddy took up saying. “My man! Peoria!” This new nickname seemed to equally confuse and appease Leonard, and once Teddy felt Leonard was less skittish, he ramped it up with unpredictable shout-outs: “Hey, Tin Man!” across campus. “Hey, Dorothy!” across the dining hall. “Hey, Ozzie, my friend. Ozzie Oz!” down the hall.

Within a month, Leonard looked tired. But also less naive. Teddy gave himself credit for this ripening, but something about it nagged him, too. What it was, he couldn’t explain. There was just a general unease about what he’d taken upon himself to do. Teddy sensed he either needed to call it quits or double down to make himself feel better. And one night, at odds with himself, he wandered up to Leonard’s room to get an idea of how he needed to proceed.

“Nebraska,” he heard himself say unexpectedly as he knocked on Leonard’s door. “It’s your biggest fan. Teddy.”

There was a long pause and then Teddy heard a quiet “Come in.”

Teddy opened the door slowly and took a peek inside. Then he threw the door open wide in awe. “Holy shit!” Teddy said. “This is some setup you’ve got here.”

Leonard looked up at Teddy from his desk. He wore magnifying spectacles and had been tinkering with something miniscule. His eyes grew bigger than big at Teddy’s praise. “You think so, Teddy?”

Teddy wandered around the room with his arms crossed in front of him while he inspected Leonard’s displays. “So I think, Leonard. So I think.”

Leonard’s room was nothing short of a museum, a war museum to be exact, but which war exactly was lost on Teddy who knew little about history other than his own personal one. “What is all this stuff?” he asked. “How’d you fit all this into your suitcases?”

“Revolutionary War replicas,” Leonard said. “Uniforms, bullets, buttons, and the like.” Leonard smiled, quickly regaining his day-one enthusiasm and speed. “My mother’s been mailing it to me. I make everything to be as authentic as possible. I’m a faker-maker, you could say. Nothing I create is the real thing, but it passes as such all the time.”

Teddy smiled. “So you scam people?”

Leonard took off his spectacles and set down his tools. “Of course not!” he said. “Absolutely, resolutely not. I make things for myself and occasionally museums.” He stood up from his desk and dug through a stack of photographs. “I had one museum request a pair of colonial boots, and, by Jove, I made them a pair of colonial boots. See? Here you are.” He held up a photograph in front of Teddy’s face. The boots in question looked like a pair of women’s old shoes. “You can’t tell the difference between these and George Washington’s. I ran over them with my father’s John Deere to break them in, and then I oiled them and ran over them, oiled them and ran over them, and then finally packed them in some dirt for a week until … abracadabra! Museum quality.” Leonard beamed like he had on the first night, before the lentil loaf and wine had gotten the best of him. “My grandmother thinks I crossed the Delaware in a past life. I’ve been eat up with this stuff since I was three.” Leonard went to the yam-colored cosmetic case and brought it to Teddy. “Open it,” he said.

Teddy looked at Leonard’s ecstatic face. The horse was completely off its lead now. Teddy was going to have to start from scratch. “Go on,” Leonard urged. “Look inside.”

Inside the case was a velvet box about the size of a sandwich, and inside of that was what appeared to be dentures. “They’re Washington’s teeth,” Leonard gushed. “Well, a replica of. They took me a year to make. I made them out of pork ribs. Well, pork rib bones.”

Leonard was on cloud nine. Teddy thought for a moment of how he might knock him down to cloud two or three. He closed the velvet box and put it back into the case and gave a long, drawn-out sigh. “You know, Peoria, the Collective was founded during the Vietnam War.” Teddy handed the cosmetic case back to Leonard who seemed to wilt a little. “Thirty years ago, some honest-to-goodness flower children got together on this campus in the name of peace and petitioned for their own cooperative dormitory.” Teddy looked for a place to sit, but finding none, went and leaned against Leonard’s desk, knocking several small tools to the floor in the process. “These were peaceable student-activists who wanted to live in harmony … cook together, bang on some tambourines, stand up to injustice. They didn’t believe in Wall Street or mousetraps or razors. And they sure as shit didn’t believe in war.”

Leonard went from looking discouraged to scared. “Oh, I’m as peaceful as they get, Teddy. I’m just into the history of it. That’s all. Really.”

Teddy leaned up from the desk, and more tools fell to the floor. He knew good and well that the present-day Collective was more drugs than hugs, a gathering of imposters—young men and women who hailed from money but dressed as if they didn’t. Potheads with no political agenda who ate beans for show but prime rib when they went home to their parents’ country houses. “I believe you, Leonard,” Teddy said, positioning himself as Leonard’s one and only confidante. “But the others wouldn’t.” Teddy took a final stroll around the room with his arms crossed, as if now assessing a police lineup. “We’ll keep this just between the two of us, okay?”

Leonard nodded silently, and Teddy let himself out. Alone in the stairwell, Teddy paused between the third and second floors. He could hear his own heart pounding. He knew he was terrible. He knew he was being just plain rotten. He didn’t know why he’d ever started in on Leonard in the first place. He’d never acted like this in his entire life, at least not that he could recall. On some occasions maybe he had been a little arrogant, but this behavior was just above and beyond, and Teddy knew it. Far off, from some Collective dorm room, Teddy could hear a whoop of laughter and bongo drums. What a charade, some voice inside his head said. A never-ending costume party. Teddy’s stomach gave a little flip. Maybe he could lay off a little. Maybe he could give the horse a vacation from training, let it out to graze.

Teddy went down to his dorm room and lit what was left of a joint. He pinched it between his fingers like a dead, white moth and turned off the lights. He lay down on his futon and let himself remember Leonard in the doorway the first night. How his amber hair lit up like a halo. How he stacked his luggage like a child stacked building blocks. Teddy let himself feel guilty about everything for a while. He even went so far as to say a prayer, which was something he hadn’t done since he was maybe seven when he’d wished to God that his parents would stay together, which they hadn’t. Please let Leonard like me, the prayer went. Please let Leonard think I’m a good guy. Teddy repeated the prayer again and again until he felt certain his prayer would be answered. After a while, he fell asleep peacefully and without remorse.

Teddy did the best he could to ride Leonard less hard. He stuck with “Peoria” and “Ozzie” and dropped “Nebraska” and “Dorothy.” A few times a week, he went by Leonard’s room to watch him work. He’d sit on the bed, and Leonard would sit at his desk, and for a while, Leonard would talk about Illinois, the family farm, the cow he’d raised that won a trophy, the way his mother made three-day beans. Sometimes he amused Teddy with rural tales he swore were true, like how he’d trained a cat to nurse a litter of possums or how a tornado had once corked their chimney with a live goat. One day, however, he really set Teddy’s head spinning with the casual announcement that his maternal grandfather was a full-blood Shawnee.

Teddy snorted. “Please. I refuse to go on believing your 4-H bullshit.”

Leonard kept at work at his desk, intent and scraping. “It’s true blue,” he said calmly. “I’m related to Tecumseh. He’s my great-times-five grandfather. Great, great, great, great, great.”

Teddy sat up on Leonard’s bed and stared. “Stop yanking my chain,” he said. “What sort of Indian sits around on his blond ass making Revolutionary War collectibles?”

Leonard scraped and scraped. “No man is without conflict,” he said. “That’s what Walter Salts always says.” Leonard turned around and gave Teddy a big, mid-American grin. “You should try to get into the enemy’s shoes some time. To see things from the other side.” Leonard turned back to his work. “My father says if you don’t fight the war on the inside, you’ll fight it on the outside.”

Teddy didn’t know what to say. Leonard suddenly struck him as complicated. If Leonard was telling the truth, he was a hypocrite. If he was lying, then he was everything Teddy had never imagined he could be. Teddy sat and stared at the back of Leonard’s 24-karat head until he could name the feeling he felt. Impressed. Leonard turned as silent as a monk, and Teddy sat in admiration until the whole room went golden and time stopped and the two of them were suspended in amber. Teddy watched until all he could see was a column of light. Until all he could hear were the soft sounds of industry. The next thing Teddy knew, he was waking, blissful, in Leonard’s bed. Leonard stood smiling at the bedside looking down at Teddy. In one hand, Leonard held his scraping tool. The other hand, empty, reached out slow and tender to brush Teddy’s cheek.

“You fell asleep,” Leonard laughed gently. “Right on my bed like a big ole teddy bear.”

Teddy’s face burned where Leonard had touched it. Teddy put his own palm to his cheek and sat up, overcome with a sudden, inexplicable sorrow that he quickly replaced with anger. “I have to go,” he said, his palm still on his cheek. “You shouldn’t have let me stay so long.” Then Teddy rose and left without another word.

After that, Teddy didn’t go back to Leonard’s room. In fact, he avoided him altogether for a good while out of fear. Then one October morning, Teddy saw Leonard alone at breakfast. Leonard looked lost and vulnerable, like he had the first day, and Teddy joined him at the table despite himself.

“Making any boots?” Teddy asked. “Any pork rib dentures?”

Leonard lit up like a harvest moon and set down his milk. His upper lip was foamy. His eyes were bright. It seemed to Teddy he had grown more pure and perfect in his absence. “Why, yes I am. Thank you for asking,” Leonard said. “My great uncle wants a set of Washington teeth. He knows a fellow who knows a fellow who knows someone who works at a famous history museum, which is actually located right here. Well, not here in New Hampshire, but here in the United States. Massachusetts, maybe.” Leonard leaned forward confidentially. “This could be a big break for me, Teddy. I mean, I’d still go to school here and get my history degree, but I’d have something waiting for me when I got out.” Leonard looked as if he might cry from joy, and Teddy’s stomach did the same somersault it had the night he’d resorted to prayer. “Don’t say anything, promise? I know you won’t. You’re the best friend I’ve got here, and I trust you.” Then Leonard reached out and touched Teddy’s hand on top of the table and answered a prayer. “You’re a good guy, Teddy.”

Teddy felt his hand go hot and his brain go cold. He shot up from the table with such force his tin plate clattered to the floor. “Don’t do that,” Teddy commanded. “Not ever.”

With that, Teddy ran from the Collective and out to the campus’s far field. When he made it halfway across, he stood in the damp morning grass and leaned over with his hands on his knees and was sick. He stayed that way for some time, fearing he might collapse if he straightened his spine. Bent over, Teddy fought against something inside himself that he couldn’t name and was sick again. Maybe the problem was that the horse hadn’t been trained at all. Maybe Teddy had let it out to pasture before it had learned a single thing. Teddy remembered the woman and the show horse. He remembered her whip, rare but ready. He wondered what kind of horse she had ever had to use it on. Maybe it wasn’t on one that was too wild, but on one that was too mild. Teddy spit into the grass and put his hands on his hips. He decided that was the case. If he didn’t act fast, Leonard would wither before Thanksgiving. Teddy frowned for a long time at a span of yellow maples. When he had come up with a good plan, he went on to class empty-handed so he wouldn’t have to go back and chance Leonard.

Teddy’s original plan was to feed Leonard a few pot brownies in the common room. A gathering of Collectives would put on some Pink Floyd, pass around a plate of cosmic fudge, and the next thing everyone knew, Leonard would break free of his cornhusk. It would be like attending the birth of a baby. Everyone Teddy ran the idea past thought it was the greatest undertaking The Collective could ever attempt. But then things got out of control. Teddy made the mistake of mentioning Leonard’s war hobbies. He made the mistake of mentioning the Washington teeth and Tecumseh and the goat in the chimney and the colonial boots. He made the mistake of picking Leonard’s dorm room lock while Leonard was at class and taking a bunch of Collectives on a tour of Leonard’s collectibles. They tried on his wigs. They tried on his tricornered hat. They laughed and laughed until they had a better idea than pot brownies in the common room.

“A tea party,” someone suggested.

“Like a Boston one,” someone countered.

At that point, Teddy knew it was beyond him. But having it beyond him relieved him of responsibility, so Teddy gave his blessing. An enthusiastic one.

“Your only job is to get him there,” Howie Ames said.

“Dressed as George Washington,” Gavin Thomas said.

Leonard wasn’t too keen on going in uniform after what Teddy had told him about the original flower children, but after a few brownies, Leonard didn’t know Illinois from Nebraska.

“You look great, Peoria,” Teddy said, as he buttoned Leonard’s waistcoat. “More all-American than ever.”

Leonard didn’t respond. His eyes were big and black, as empty as a shark’s. Teddy equipped Leonard with a cardboard musket and straightened his wig, and the two presidents went out to the far field where a bonfire the size of a teepee raged.

“They’re coming!” someone shouted when they saw Teddy and Leonard approaching.

“Who’s coming?” a chorus asked.

“The British!” another chorus answered. “The British, The British are coming!”

Though incorrect, Teddy found this hilarious, but Leonard, in the flickering, distant glow, stopped in terror.

“Come on, Peoria,” Teddy said. “The party can’t go on without you.”

And that was when Leonard took off, fast and frantic. He had an unexpected agility, and Teddy thought, with some level of parental admiration, that maybe he had, once again, underestimated him. Maybe he knew nothing about him at all. He watched with awe and horror as Leonard made for the dark span of distant maples, where the far field met the wilderness. The Collectives, beyond inebriated, were delighted by this unexpected turn.

“Go, Nebraska, go!” someone hooted.

“All the way to Mount Vernon!” another shouted.

In the glow of the bonfire, all that Teddy could make out as he tried to follow Leonard’s retreat was the white wig bouncing in the night, growing smaller and smaller against the jagged silhouette of the forest like the terrified end of a cottontail. A chorus of laughter followed when the wig could no longer be seen. It was laughter that soon faded to an intoxicated murmuring and later to a glazed glee of stupidity.

When the sun came up a few hours later, innocent over the woods, no one seemed to recall what had happened—to Leonard or themselves. The fire was now nothing but a handful of ashes. The discarded baking pans and tambourines dotted the scene like battle shields. The Collectives eventually rose up from beneath their dewy blankets and squinted out empty at the world, before staggering back into the dormitory for eggs and sleep.

Teddy’s fear unfolded with the day. At first, his anxiety was manageable. He stayed out in the far field for the morning, picking up debris, pouring warm beer in the ashes, staring off at the maples in the hopes he’d soon see Leonard emerge, rumpled but golden, shaking his head in good humor, holding his flattened wig in one hand and waving Hello! Here I am, Teddy! with the other. But by noon, there was no sign of Leonard, neither in the Collective nor in the field, so Teddy went off into the woods on his own. He kept reminding himself of Leonard’s unexpected agility as he walked. He reminded himself that Leonard had grown up on a farm and had raised a cow from calf to bull. Teddy tried to imagine Leonard strolling over fallen trees and whistling with the birds, but instead he saw him pale and dead on a bed of crimson leaves. He tried to imagine Leonard sitting on a stump in his Revolutionary garb, buttoning his boots and reciting the Preamble, but again, Teddy saw him dead and white, his eyes open in a last moment of panic that Teddy had orchestrated.

Teddy came back from the woods in the late afternoon. By the time the sun began its descent, Leonard still had not returned, and Teddy was near panic. He called a meeting of all the Collectives, but some were in too poor of shape from the night before to attend, and of those who did, nearly half of them found Leonard’s absence insignificant.

“Nebraska’s fine,” Gavin said. “Schoolchildren have eaten worse brownies.”

“He’s probably in town,” Howie said. “Have you even checked the diner? Twenty bucks he’s there right now drinking a six-pack of milk.”

Teddy gnawed his bottom lip. “I think we should tell the administration. Maybe campus security.”

There were some audible groans, and Gavin shook his head. “Leave the school out of it. The kid’ll turn up eventually. Dapper and dumb as ever.”

The meeting adjourned without Teddy’s blessing. Teddy went up to Leonard’s room to see if he had crept back into The Collective when no one was watching. But Leonard wasn’t there. Teddy sat at Leonard’s desk and turned on the desk lamp. He tried on Leonard’s magnifying glasses. He scraped at a brass button with a dental tool. Then he took off the glasses and curled up on Leonard’s bed and prayed the prayer he’d prayed before, plus one more. Please let Leonard like me. Please let Leonard think I’m a good guy. Please let Leonard be alive.

Three days later and three towns over, Leonard was eventually found. He wasn’t dead, but he was dehydrated and weak and had a broken arm. The Collective gathered around the common room television to watch the local news. Leonard was still dressed as a soldier. He still had on his old wig, as well as a new cast, as two policemen helped him into a cruiser.

“Look at him!” Gavin said. “He’s as white as a sheet.”

“Check out his eyes,” Howie said and whistled. “They don’t look real.”

Teddy hung back in the common room and stared at the floor while the newscaster gave his report. Leonard had been found on an elderly couple’s front porch. When confronted, he’d told authorities he was the first president of the United States and that he was originally from Nebraska. Thanks to a student ID, the cops were able to determine that his name was Leonard Salts and he was from Ursula, Illinois. He was now in good hands and being sent back to his parents, accompanied by a school counselor. “He’s a lucky young man,” the newscaster said in closing. “He was pretty bad off when he was found.”

The Collectives, save for Teddy, clapped when the segment cut to a commercial.

“All’s well that ends well,” one said.

“Talk about making history,” said another.

Teddy skipped class for the rest of the week. On Saturday, a tall, sad man, accompanied by a dean of some sort, came to pack up Leonard’s things. Teddy stood in the hall and listened while they wrapped Leonard’s creations in newspaper.

“I can’t figure out what went wrong,” the tall man said. “Leonard always had a good head on his shoulders.”

There was a long silence. Teddy’s stomach spun one way and then another.

“Some people do better close to home,” the administrator finally said. “I’m sure he’ll bounce right back once he gets back to what he knows.”

Teddy left the hallway and went to his room. An hour later, he watched from his window as the tall man and the dean walked from the Collective with the yam-colored suitcases and a dolly full of cardboard boxes. Teddy watched until they disappeared around a wooded bend in campus. He watched the bend until the sky was black. Teddy couldn’t stop thinking about Leonard or the teeth in the velvet box. He couldn’t stop thinking about the museum waiting for the teeth and how they might never receive their order and Leonard would lose his chance. But mostly he thought about watching Leonard work—his bent back and the gentle scrape of his tools and the slow evenings suspended in amber.

Teddy sank into a deep depression. Within a week, he took a leave of absence before Thanksgiving break and went home to his mother in Massachusetts. She babied him with soup. She gave him half of her Prozac prescription. Teddy spent his time sleeping and reading his old comic books and trying not to think about Leonard. On Thanksgiving, Teddy picked up the phone and called Information and got a number for a Walter Salts in Ursula, but before he could convince himself to call, he burned the piece of paper the number was on. He lit a match and held it to the paper and dropped the paper right before it burned his fingers. The ashes of Walter Salts’s number left a little brown scar on Teddy’s white bedspread.

“Why don’t you go somewhere after the holidays?” his mother suggested. “Somewhere where people have it really bad? A place that will make you feel better about yourself?”

Teddy was doubtful, but he took her advice. In January, he went somewhere hot and humid and primitive—a place where he was tall and godly and the bearer of good and necessary things. It turned out his mother was right: seeing people worse off than himself really did put Teddy in a better mood. Before long, his spirits soared. He saw himself as a benevolent king. One who was good with a shovel, a soup ladle, a campfire guitar. Teddy gained approval, mostly from himself; he grew nearly giddy with self-righteousness. By the time he returned to the States that summer, Teddy had, for all intents and purposes, erased Leonard Salts from his memory.

Years later on a Sunday drive home from the beach, Teddy stopped at a rest area with his young family. It was a dark and dated pit stop, but it had clean-enough bathrooms, and while Teddy’s wife tended to their son and daughter, Teddy stood in the vestibule with his hands on his hips and stared at the vending machines. He peered into one that offered crackers and chips, and then into a second that offered water and juice, before he finally paused to consider the space between the two machines. There, tucked in the shadows and bolted to the wall, was a small, nondescript box. Curious, Teddy moved closer and saw that the box was made of glass and steel. It was smudged with fingerprints but inside were a set of yellowed false teeth and three brass buttons and a neat row of crude bullets. Teddy frowned. He felt his stomach do a little flip, and he leaned in closer still. There wasn’t a plaque anywhere to be found, just a little strip of paper inside the box, upon which was typed the word: REPLICAS. Teddy bent over until his nose touched the box. He stared until his eyes watered. For a moment, he could hear the scraping of Leonard’s tools and was back on Leonard’s bed, suspended in amber, right at the threshold of the afterlife. He saw Leonard’s nimbus of hair, felt Leonard’s warm hand on his cheek. He heard Leonard say: You’re the best friend that I’ve got here, Teddy. You’re a good guy.

And then: his wife and children. Loud and soapy and fresh, their shoes squeaking against the floor. “Vending machines!” they squealed. “Can we have quarters, Daddy? Can we? Can we?”

Teddy couldn’t speak. Their presence was suddenly tin plates clattering all around. He stormed from the rest area and went out to the car and sat panting behind the wheel. When his wife and children finally climbed back in, Teddy started the car and gunned the engine. He put all the windows down and drove off, fast and erratically, first in one lane and then in another. In the roar of the hot summer wind, as he sped westward, Teddy could once again see the horse. It had gone mad from fear and was galloping toward the horizon in a cloud of dust. Behind it, clinging to the training lead, was Teddy. He thought he had let go long ago, but he realized he never had. He realized he never could, even if he wanted to.

Terrifying. But I couldn’t put it down. Thanks!

This one is a treasure. Thank you.