Dear Reader,

For me, the last normal day of life was Wednesday, March 11, 2020. I was the coach of a middle school girls rec basketball team, and that night, we had what would be our last practice. We were getting ready for the playoffs, which began that Monday. My teams had won the championship two of the past three years. We were not the favorites, but we were peaking at the right time, and I liked our chances.

Before I went to the gym that night, I knew, on some level, that this would be the last time these girls would have the opportunity to play basketball for a while. So I didn’t run any drills. I let them scrimmage the whole time.

When I got home that night, I learned that the NBA was shutting down its season. Our rec league would soon follow. The playoffs never happened. We never got to crown a champion. I don’t think my kid, who would have been a major contributor had we made a deep playoffs run, has so much as picked up a basketball since that night.

Everyone has a story like this, of course. Mine is not special. The last two years have been long on loss, and short on magic.

To survive the quarantine, I leaned into it. I focused on the introverted parts of my nature, and ignored the rest. I took long, solitary walks around the deserted campus. I watched the birds. I did a lot of writing (as you, Dear Reader, have seen). Social time was spent, invariably, in my home office, leaning on the desk like I was sitting at a bar, against the bookcase backdrop familiar to anyone who has watched me on Narativ Live or Stuttering John. There could be no parties, no concerts, nothing of the kind, so I trained my mind to forget about all that. Even when the restrictions lifted, I rarely went out—just the occasional dinner with my wife.

This week I found myself in New York City, my old stomping grounds. I was there on business, unavoidably, but if I was going to spend time in the city, during an omicron surge, I was not going to stay locked like Rapunzel in my hotel room. Wandering alone around Gotham, open to adventure, is one of life’s more underrated pleasures. Anything can happen. And after almost two years of veritable house arrest, even the smallest things bring pleasure.

A cab ride, for example. I know Uber and Lyft are more efficient than a yellow taxi, but there is something magical about the randomness of the New York cab ride. You stride into the street, hunting for the “for hire” lights. You extend your arm and wave it. The car sees you, puts on the blinkers. And you hop into a car, driven by a random stranger, who conveys you to where you want to go. Driving up Madison Avenue, I beheld all the shops, the flagship stores for fancy designers of fashionable clothing, for handbags and crystal glassware, for bridal gowns and women’s shoes. The amount of creative energy necessary to open even one of those stores boggles the mind, and here they all are, lined up like squares on a Monopoly board, a surfeit of human ingenuity.

I had dinner by myself, at Smith & Wollensky, an old school steakhouse in Midtown. I wasn’t sure if I’d need a reservation, but there were plenty of tables, and the host, dapper in his smart suit, looked happy to see me. It’s strange, having to show paperwork to enter a restaurant, but it’s not like I’m not used to being carded going out in Manhattan. He seats me at a table by the bar, 12 feet away from anyone else.

I put my phone on the table and flip it over. It is such a temptation to look at the device, especially alone at a restaurant, but I want to soak up the atmosphere. The bartender is Irish, with a glorious brogue. There are a half dozen men at the bar, all in suits. For a moment, I feel underdressed, in my button down and jeans. Then a older guy with long white hair and a stringy beard walks by, wearing a sweartshirt that says STURGIS BIKE RALLY 2021. The thought crosses my mind that he is probably proudly antivax, but then I remember that he can’t set foot in the restaurant without proof of vaccination. Relief! He and his friend, who is wearing a suit, move along into the restaurant proper, and I am left to drink in the scene.

Everyone seems happy just to be there, to be together at a bar, and have that once again be normal and fun. My dinner is a New York strip, mashed potatoes, and a glass of wine. With tip, the bill is a decadent $129—and worth every penny. These are the little things, the small pleasures, that help balance out the loss.

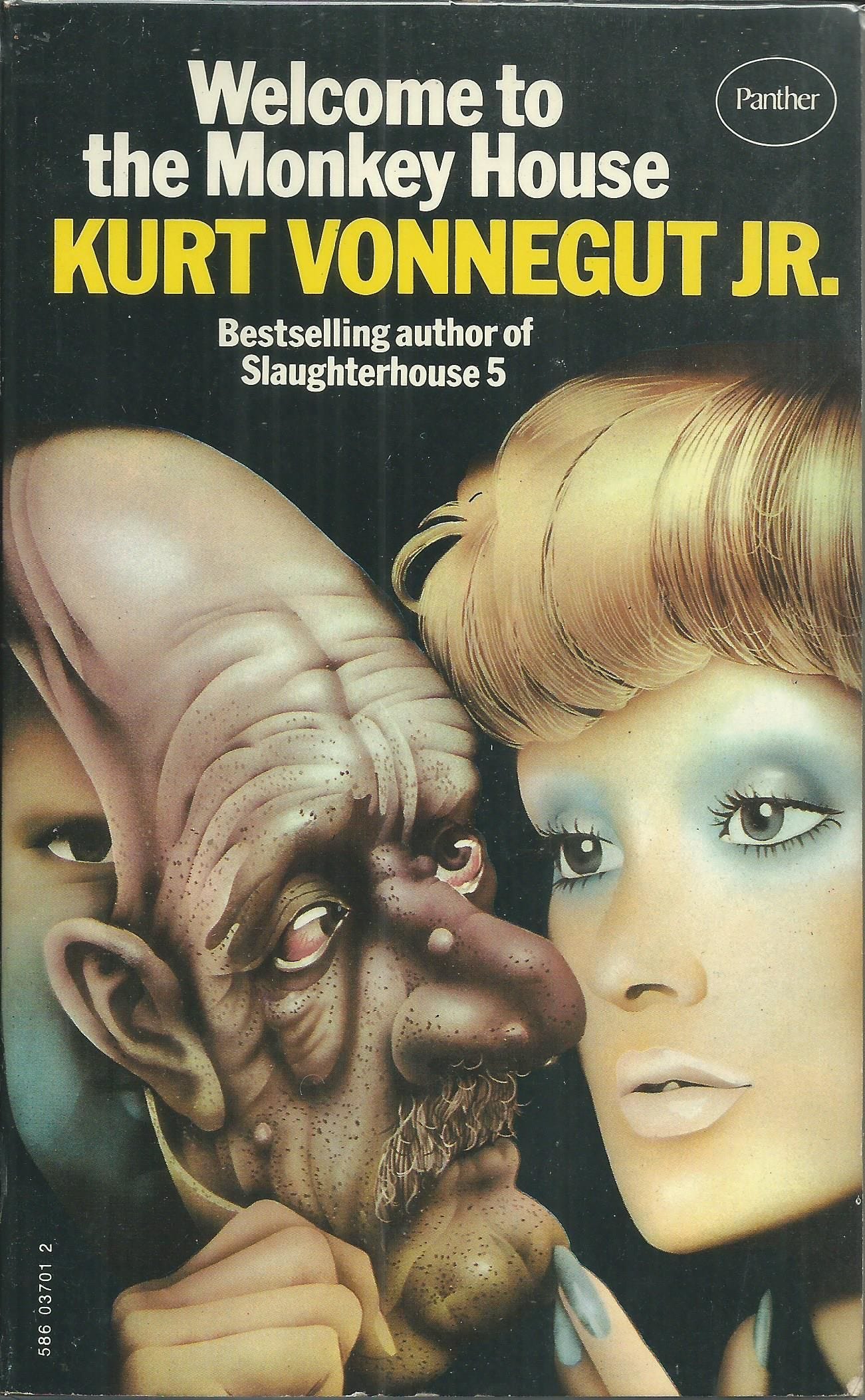

All of this called to mind a short story by Kurt Vonnegut, “Harrison Bergeron.” I read the Vonnegut stories at a formative age, and Welcome to the Monkey House is probably more important to me than other people. Those stories helped me hone my writerly sensibilities, for better or worse.

“Harrison Bergeron” is very short, and begins thus:

THE YEAR WAS 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.

Some things about living still weren’t quite right, though. April, for instance, still drove people crazy by not being springtime. And it was in that clammy month that the H-G men took George and Hazel Bergeron’s fourteen-year-old son, Harrison, away.

They take him away because he is a genetic marvel—bigger, stronger, smarter, handsomer, nimbler than other humans. In the story, George and Hazel are watching a variety show on television when their son, who has escaped from his confinement, shows up on the set:

The rest of Harrison’s appearance was Halloween and hardware. Nobody had ever worn heavier handicaps. He had outgrown hindrances faster than the H–G men could think them up. Instead of a little ear radio for a mental handicap, he wore a tremendous pair of earphones, and spectacles with thick wavy lenses. The spectacles were intended to make him not only half blind, but to give him whanging headaches besides.

Scrap metal was hung all over him. Ordinarily, there was a certain symmetry, a military neatness to the handicaps issued to strong people, but Harrison looked like a walking junkyard. In the race of life, Harrison carried three hundred pounds.

And to offset his good looks, the H–G men required that he wear at all times a red rubber ball for a nose, keep his eyebrows shaved off, and cover his even white teeth with black caps at snaggle-tooth random.

As his parents watch, not quite sure what to make of it, Harrison removes all of those hindrances, every last one, declares himself Emperor, and takes as his bride one of the ballerinas:

Harrison placed his big hands on the girl’s tiny waist, letting her sense the weightlessness that would soon be hers.

And then, in an explosion of joy and grace, into the air they sprang!

Not only were the laws of the land abandoned, but the law of gravity and the laws of motion as well.

They reeled, whirled, swiveled, flounced, capered, gamboled, and spun.

They leaped like deer on the moon.

The studio ceiling was thirty feet high, but each leap brought the dancers nearer to it. It became their obvious intention to kiss the ceiling.

They kissed it.

And then, neutralizing gravity with love and pure will, they remained suspended in air inches below the ceiling, and they kissed each other for a long, long time.

It was then that Diana Moon Glampers, the Handicapper General, came into the studio with a double-barreled ten-gauge shotgun. She fired twice, and the Emperor and the Empress were dead before they hit the floor.

“Harrison Bergeron” could easily be misread as a libertarian text, a call to eschew masks and vaccines. Certainly it warns of government overreach. And Vonnegut, one gleans from the story, is no fan of Participation Culture trophies.

But that’s a surface reading, and omits the true spirit of the piece. For me, the story is about embracing who you are. We all of us have talents that we should nurture and express, innate abilities we are duty-bound not to squander. It’s also about embracing the moment. Harrison Bergeron is dead at 14, but he lived more in the last two hours of his life than almost anyone in Vonnegut’s fictional 2081 America.

We have to pick our moments to shine. To live, we must live.

Pass the steak sauce.

POSTSCRIPT

We have been focused intently on the pandemic, with good reason. A million Americans are dead, Long Covid afflicts god knows how many more, and we still don’t know how this will all play out. But the coronavirus is not the only ordeal people have to contend with.

In September, I ran a haunting piece by my friend Nelly Reifler on “Sunday Pages.” Recently, she found out that her partner, D. Foy—a wonderfully talented writer—has bone marrow cancer. He is, Nelly writes, “hovering between stages two and three.” She has set up a GoFundMe to help with the expenses for his treatments—which are enormous.

These are good people, artists, and they are struggling. Please help if you can. Thank you.

I was in cancer treatment for two years, 2012-2014. (No immune system, so I couldn't go anywhere without a mask. Most particularly I was told to stay away from kids.) It was useful preparation for covid. I started a blog, that no one read, during that period. Silence and stillness are gifts.

Lived in New York City for 26 years. I still miss it. But I don’t miss the rent. I miss the bagels, Sherry Lehman, St. Patrick’s Cathedral: my parish, my doctors there. But not the avaricious landlords and real estate agents. I’m glad you enjoyed yourself Greg. Pass the red sauce!