Dear Reader,

According to the critic Harold Bloom, who would know, Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel, is the single most analyzed piece of literature in college English departments the world over. He attributes this to the book’s “unique propensity for ambiguity.” While it is certainly true that Conrad has a flair for the ambiguous, I think the reason is less lofty than Bloom pretends. Having taught creative writing as an adjunct, and thus presided over class discussions in which not a single person is familiar with the assigned material, I believe that professors teach the book because it’s short, so there’s more of a chance their students will have actually read the damned thing before class.

To wit: I have read Heart of Darkness twice. The first time was in high school, quickly and in one sitting, having forgot that it was due the next day. The second time was last night, quickly and in one sitting, having decided to write about it for today’s “Sunday Pages.” In both cases, the speed with which I plowed through the text stood in stark contrast to the slow, unsteady journey of our melancholic narrator into the dark and unknowable heart of Africa. (In both cases, I finished the entire book in less time than it would take to watch Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s mesmerizing film that transfers the action of Heart of Darkness from the jungles of the Congo to the jungles of Vietnam.)

And when I call it a “damned thing,” I mean what I say. Heart of Darkness is—among many other ambiguous things—the story of a man in purgatory hunting down a man who is damned.

Charlie Marlow is the captain of a steamer owned by a Belgian concern that deals in ivory. He is sent to the imperial colony with the Orwellian name Congo Free State to fill a vacancy occasioned by the homicide of his predecessor, a Dane named Fresleven, whose remains he will eventually find, tall grass growing through the rib bones. Once at the Central Station, he must repair his boat and take it up the river, where the Company’s best accumulator of ivory is “at present in charge of a trading-post, a very important one, in the true ivory-country, at ‘the very bottom of there. Sends in as much ivory as all the others put together...’” This is Mr. Kurtz, a man of boundless talent, intellect, and ambition—so great that only Marlon Brando could possibly play the role in the movie—feared to be both deathly ill and off his rocker. In Apocalypse Now, Willard is sent to kill Kurtz; in Heart of Darkness, Marlow is sent to rescue him—or, at the very least, to rescue his hoard of ivory.

The plot centers on this journey into the great and terrifying unknown, where geography symbolizes psychology: Marlow gets the job through an influential aunt, he travels to Africa, he repairs his broken steamer, he meets a series of unwell people, he makes his way to Kurtz, Kurtz dies almost immediately. Slow descent into madness; simple enough.

The structure, however, is odd. The book begins at the mouth of the Thames, where a small group of men sit on a sailboat, waiting out the high tide. The sun has just set, and to pass the time, Marlow relates his dark tale. What we’re actually reading, then, is a transcript of the story, set down by another passenger on the sailboat. Thus we are at one remove from the action, with our chronicler relaying another narrator’s narration.

Thirty-five years later, I still recall our class discussions about Heart of Darkness. Strewn through its 48,000 words are half a dozen canonical passages that, even if you aren’t familiar with them from English class, make you sit up and pay attention. Here, for example, is Marlow expressing, or trying to express, the nightmarish quality of his experiences in the Congo with Kurtz:

Do you see him? Do you see the story? Do you see anything? It seems to me I am trying to tell you a dream—making a vain attempt, because no relation of a dream can convey the dream-sensation, that commingling of absurdity, surprise, and bewilderment in a tremor of struggling revolt, that notion of being captured by the incredible which is of the very essence of dreams....”

He was silent for a while.

“... No, it is impossible; it is impossible to convey the life-sensation of any given epoch of one’s existence—that which makes its truth, its meaning—its subtle and penetrating essence. It is impossible. We live, as we dream—alone....”

Kurtz winds up being both a man of genius and a man of madness. Lazy commentary suggests he has “gone native,” but that reading is both racist and untrue. Yes, he has set up shop among the inhabitants of this most uninhabitable part of the jungle. But he does not adopt their mores and traditions, does not appropriate their culture, does not admire it. Instead, he uses chicanery and gunpowder to trick them into worshiping him as a sort of god. As Marlow explains:

. . . I learned that, most appropriately, the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs had intrusted him with the making of a report, for its future guidance. . . . [I]t was a beautiful piece of writing. The opening paragraph, however, in the light of later information, strikes me now as ominous. He began with the argument that we whites, from the point of development we had arrived at, ‘must necessarily appear to them [savages] in the nature of supernatural beings—we approach them with the might of a deity,’ and so on, and so on. ‘By the simple exercise of our will we can exert a power for good practically unbounded,’ etc., etc. …. There were no practical hints to interrupt the magic current of phrases, unless a kind of note at the foot of the last page, scrawled evidently much later, in an unsteady hand, may be regarded as the exposition of a method. It was very simple, and at the end of that moving appeal to every altruistic sentiment it blazed at you, luminous and terrifying, like a flash of lightning in a serene sky: ‘Exterminate all the brutes!’

And exterminate them he did. When Marlow gets to the hovel where Kurtz is living, he finds it ringed by pikes crowned with the shriveled heads of dead natives. The natives who are not dead fear his random outrages and thus obey his every command; they are the ones who collect the copious quantity of ivory piled all around the hut. And a native woman, bejeweled and beautiful, he has taken as his lover.

The extent of what Kurtz has done, in his mad pursuit of fortune and favor, Marlow does not tell us—he may not even know himself—but there is no question that Kurtz’s “methods,” to use the understating language the petty, jealous Manager employs, are “unsound.” Contemplating the depths of his depravity on his deathbed, Kurtz himself can only summon two words, the last he will utter before passing from this vale of tears to the real heart of darkness. For the full effect, he repeats them:

“The horror! The horror!”

Another famous passage occurs at the end of the book. Marlow has returned to Brussels bearing Kurtz’s papers, which he refuses to surrender to the Company, even when threatened with a lawsuit. Instead, he seeks out the dead ivory dealer’s fiancée, known to us only as His Intended, to give her the papers. A year later, she is still in mourning clothes, unable to process the death of her beloved. Marlow, a seaman who is hardly ever around women and hasn’t the first idea how to comfort this grieving widow, is taken aback at her outburst of emotion at learning he was with Kurtz when he died:

“‘To the very end,’ I said, shakily. ‘I heard his very last words....’ I stopped in a fright.

“‘Repeat them,’ she murmured in a heart-broken tone. ‘I want—I want—something—something—to—to live with.’

“I was on the point of crying at her, ‘Don’t you hear them?’ The dusk was repeating them in a persistent whisper all around us, in a whisper that seemed to swell menacingly like the first whisper of a rising wind. ‘The horror! The horror!’

“‘His last word—to live with,’ she insisted. ‘Don’t you understand I loved him—I loved him—I loved him!’

“I pulled myself together and spoke slowly.

“‘The last word he pronounced was—your name.’

“I heard a light sigh and then my heart stood still, stopped dead short by an exulting and terrible cry, by the cry of inconceivable triumph and of unspeakable pain. ‘I knew it—I was sure!’... She knew. She was sure. I heard her weeping; she had hidden her face in her hands. It seemed to me that the house would collapse before I could escape, that the heavens would fall upon my head. But nothing happened. The heavens do not fall for such a trifle. Would they have fallen, I wonder, if I had rendered Kurtz that justice which was his due? Hadn’t he said he wanted only justice? But I couldn’t. I could not tell her. It would have been too dark—too dark altogether....”

This, despite Marlow’s claimed fidelity to the truth. “You know I hate, detest, and can’t bear a lie,” he explains to his captive audience, both on the sailboat and in English classes, “not because I am straighter than the rest of us, but simply because it appalls me. There is a taint of death, a flavour of mortality in lies—which is exactly what I hate and detest in the world—what I want to forget. It makes me miserable and sick, like biting something rotten would do.” And yet he chooses not to tell His Intended what Kurtz’s last words really were.

Kindness trumps honesty. The darkness has not overcome Marlow.

In literary circles, our teacher told us, that moment is known simply as “The Lie.”

The late Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe gave a lecture, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” in which he bashes Conrad for portraying Africa as “‘the other world,’ the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization,” denouncing him as a racist. And there is certainly plenty of evidence to support that argument. None of the Black characters have names. None of them are developed at all. Even the helmsman of the steamer, whom Marlow worked with and respected, is not really considered by the captain to be fully human. It is uncomfortable, sometimes cringingly so, to read some of Heart of Darkness’s more offensive passages.

And yet Marlow, despite his racist bent, sees, and calls out in the moment, some of the more egregious mistreatment of the natives by his fellow white colonizers. When told by Kurtz’s Russian aide-de-camp and disciple that the heads on the pikes belonged to “rebels,” he laughs in the guy’s face. “Rebels! What would be the next definition I was to hear? There had been enemies, criminals, workers—and these were rebels. Those rebellious heads looked very subdued to me on their sticks.” Those terms, he realizes, are cooked up by white colonizers to excuse their own inexcusable cruelty.

We must also remember that Heart of Darkness is told through an elaborate framing device, and consider its purpose. Marlow is less racist than Kurtz, certainly, but more racist than Conrad. Why create the framing device, if not to distance the real-life novelist from the made-up yarn-spinning steamer captain? Furthermore: why write the book at all, if not to shine light on the dreadful conditions in the Congo Free State, which Conrad at his day job witnessed firsthand?

Conrad never explicitly states where exactly in Africa he is. He never names the city or the country in which the Trading Company is headquartered. He never brings up Leopold II, the King of the Belgians, who owned, personally, the entire expanse. This is, I think, because Conrad feared reprisal—lawsuits, maybe, or worse. He exposes the horrors—the horrors—he saw there, especially those visited upon the native population, 1) in the form of fiction, so he can claim it is invented; 2) through a second narrator, Marlow, to give himself another remove; and 3) without being too specific, to avoid conflict with the powerful corporate world. To write this book in 1899, when the Belgians were at the height of their legendary heinousness in that colony and the zenith of their wealth, is not unbrave.

Nor is Conrad, or even Marlow, celebrating white supremacy, extolling Progress, or defending colonialism. Both men, the real and the invented, clearly disdain all of these things. Meanwhile, by far the wickedest character in the book is Kurtz, who is described as, and not by accident, as white as white can be:

And the lofty frontal bone of Mr. Kurtz! They say the hair goes on growing sometimes, but this—ah—specimen, was impressively bald. The wilderness had patted him on the head, and, behold, it was like a ball—an ivory ball; it had caressed him, and—lo!—he had withered; it had taken him, loved him, embraced him, got into his veins, consumed his flesh, and sealed his soul to its own by the inconceivable ceremonies of some devilish initiation. He was its spoiled and pampered favourite. Ivory? I should think so. Heaps of it, stacks of it. The old mud shanty was bursting with it. You would think there was not a single tusk left either above or below the ground in the whole country.

Kurtz is a full seven feet of skeletal whiteness, topped off by a shiny white cueball of a pate. He is ivory incarnate. He is, in short (kurzum in German), the whitest white man in all of Africa—and also the most evil. Conrad equates the two qualities deliberately. His Intended talks about Kurtz’s “goodness,” and no doubt Kurtz had that in some supply before he left. But by the time we meet him, all of that has evaporated. What remains is a bleached-out husk of pure horrific evil.

There is also the treasure that brought these white men to the Congo Free State in the first place: the (white) ivory. It is not Africa that drove Kurtz mad, nor the fever, the climate, the loneliness, the food or anything else in the surround; what drove him mad was greed. Kurtz went mad with greed.

Here was a Renaissance man who could have done anything, as Marlow learns later when he encounters a musician cousin in Brussels:

Incidentally he gave me to understand that Kurtz had been essentially a great musician. ‘There was the making of an immense success,’ said the man, who was an organist, I believe, with lank grey hair flowing over a greasy coat-collar. I had no reason to doubt his statement; and to this day I am unable to say what was Kurtz’s profession, whether he ever had any—which was the greatest of his talents. I had taken him for a painter who wrote for the papers, or else for a journalist who could paint—but even the cousin (who took snuff during the interview) could not tell me what he had been—exactly. He was a universal genius….

And Kurtz chose to direct all his talent and energies to…collecting elephant tusks. Neither Marlow nor Conrad say it out loud, but we are given to understand that this is an enormous waste—a squandering. All it takes to succeed as a white man in the Congo, after all, is a constitution that resists endemic disease, like the Manager’s. True genius is not required. But here is Kurtz, dead before he can even get married, all his plans and Great Thoughts lost forever, because he would do anything, summon any demon, kill anyone Black or white, to acquire a bit more booty. But hey, at least the ivory made it back to Belgium.

Reading the book in 2025, I think only of our current iteration of this kind of white man, brilliant but misguided and irreparably damaged, in this imperial nation vaster and more powerful than Belgium could ever have dreamt of being. Like Kurtz they are white supremacists. Like Kurtz they are men of talent. Like Kurtz they engage in unspeakable acts. (What happens in Leopoldville stays in Leopoldville.) Like Kurtz they enjoy the undeserved protection of corporations and governments. And like Kurtz they are driven mad with greed. The accumulation of assets is more important to them than anything: love, sex, art, creativity, fame, faith, hope, charity, decency, respect, community, God, the future of humanity—anything.

How can we read Heart of Darkness today and not think of the disgustingly wealthy white men from Africa hellbent on destroying our country and the world for their own material gain?

Another characterization of Kurtz is supplied by a journalist Marlow encounters:

This visitor informed me Kurtz’s proper sphere ought to have been politics ‘on the popular side.’ He had furry straight eyebrows, bristly hair cropped short, an eyeglass on a broad ribbon, and, becoming expansive, confessed his opinion that Kurtz really couldn’t write a bit—‘but heavens! how that man could talk. He electrified large meetings. He had faith—don’t you see?—he had the faith. He could get himself to believe anything—anything. He would have been a splendid leader of an extreme party.’ ‘What party?’ I asked. ‘Any party,’ answered the other. ‘He was an—an—extremist.’

So many memorable passages in Heart of Darkness, and that one word—extremist—is what jumped out at me last night.

On this second full read, I found myself more interested in the beginning than the end of the book. There are many ways to set up a Decameron-style frame. Why did Conrad choose a boat at the mouth of the Thames? Who are the people in Marlow’s captive audience?

The boat is a cruising yawl, which we’re told is named the Nellie. (My theory is that this piece of information is given because that is also the first name of His Intended—and thus the last word Kurtz utters, in Marlow’s false account.) There are five people on the boat, all dudes, and all Company dudes: the Director of Companies, who I take to be the CEO; an Accountant, or CFO; a Lawyer, or corporate attorney; Marlow, the erstwhile seaman, who now serves the Company in some new and unspecified capacity; and the chronicler of the book, of whom we know nothing. This is a gathering of businessmen, rich and powerful businessmen—a corporate retreat; an ORTBO—and the yawl is presumably a fine, fancy vessel. Marlow may as well be giving a presentation to his Board of Directors on the perils of the ivory trade in the Congo Free State.

One of the four men reprimands Marlow at some point; otherwise, none of the chaps say anything, or react at all, as the story is told. It is pitch black, so they can’t really see Marlow. He comes through as a Voice, like they are listening to a podcast. Do they care at all? Are they even awake? Why does Marlow decide to unload this tale at that time? Has he been waiting for the right moment to unburden himself?

Perhaps so. Certainly it has been worrying his mind. He begins like this:

—“I was thinking of very old times, when the Romans first came here, nineteen hundred years ago—the other day .... Light came out of this river since—you say Knights? Yes; but it is like a running blaze on a plain, like a flash of lightning in the clouds. We live in the flicker—may it last as long as the old earth keeps rolling! But darkness was here yesterday.

And he imagines a Roman seaman, down on his luck, who came to Britain to settle all those centuries ago:

Land in a swamp, march through the woods, and in some inland post feel the savagery, the utter savagery, had closed round him—all that mysterious life of the wilderness that stirs in the forest, in the jungles, in the hearts of wild men. There’s no initiation either into such mysteries. He has to live in the midst of the incomprehensible, which is also detestable. And it has a fascination, too, that goes to work upon him. The fascination of the abomination—you know, imagine the growing regrets, the longing to escape, the powerless disgust, the surrender, the hate.

He speaks from experience, as we soon discover. Does Marlow want his corporate companions to understand the human suffering, the spiritual anguish, necessary to secure the bottom line—to pay for their salaries, and their clothes, and their cruising yawls?

Of greater interest to me is the chronicler. This is a guy who is so fascinated by Marlow’s story that he feels the need to write it all down, to document it for posterity. Why? What does the chronicler do for the Company? Why does the story interest him and not the others? Has he also glimpsed the heart of darkness?

There is almost no editorializing in the book. All we have to go on, really, is the chronicler’s opening description of where they are and what it signifies:

Forthwith a change came over the waters, and the serenity became less brilliant but more profound. The old river in its broad reach rested unruffled at the decline of day, after ages of good service done to the race that peopled its banks, spread out in the tranquil dignity of a waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth. We looked at the venerable stream not in the vivid flush of a short day that comes and departs for ever, but in the august light of abiding memories….Hunters for gold or pursuers of fame, they all had gone out on that stream, bearing the sword, and often the torch, messengers of the might within the land, bearers of a spark from the sacred fire. What greatness had not floated on the ebb of that river into the mystery of an unknown earth!...The dreams of men, the seed of commonwealths, the germs of empires.

The sun set;

—so the book opens with the sun literally setting on the British Empire—

the dusk fell on the stream, and lights began to appear along the shore. The Chapman light-house, a three-legged thing erect on a mud-flat, shone strongly. Lights of ships moved in the fairway—a great stir of lights going up and going down. And farther west on the upper reaches the place of the monstrous town was still marked ominously on the sky, a brooding gloom in sunshine, a lurid glare under the stars.

“And this also,” said Marlow suddenly, “has been one of the dark places of the earth.”

Conrad is trying to warn us: We live in the flicker. Darkness was here yesterday. There’s no guarantee it won’t return tomorrow.

ICYMI

Great episode of The Five 8 this week, featuring the always excellent Nadine Smith:

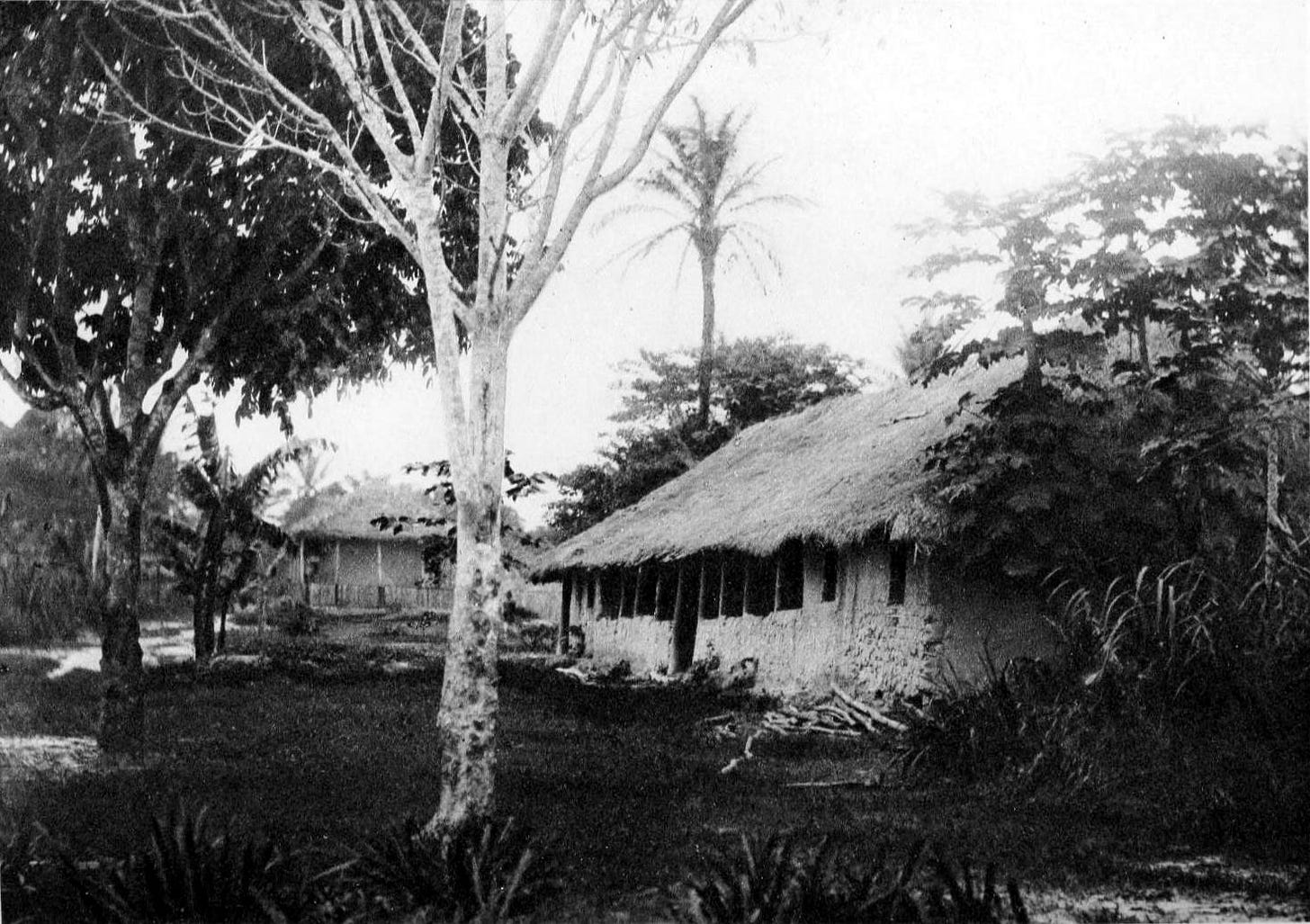

Photo credit: Delcommune, Alexandre - Vingt années de vie africaine. 1874-1893; récits de voyages d'aventures et d'exploration au Congo Belge (1922)

Very insightful Greg… I so look forward to your Sunday Pages and the chance to reflect on our times through the lens of great literature. I must re-read this, I’m sure my middle-aged self will take much more from it than teenage me could have. The moral corruption, abject greed and savagery of Conrad’s mad cult leader certainly hits me from a fresh (yet fetid) perspective now in 2025… The Horror!!!

I found a “teachable moment” with my daughter several years ago. I was trying to prove that telling the truth was the most important thing. Instead she told me about an episode of one of her tween shows where the family (with several children) decided that they would only tell each other the truth - no lying allowed. After a few days of this, everyone was mad at each other and not speaking with lots of hurt feelings. So she concluded that telling the truth all of the time could be as damaging as telling a lie. There’s a huge difference between telling a “lie” and willful deceit. The lie Marlow told to the fiancé was not to deceive her, but to extend a kindness. The truth in that situation would have been cruel. What the miscreants in the current administration are doing, and have been doing, is downright cruel and every word out of their mouths is meant to deceive us. Chaos, confusion and illusion are the tools that they use to achieve their misguided goals. Don’t believe everything you see and hear. They are masters of deceit.