Dear Reader,

I met my friend Jana Martin from my days at The Weeklings. She was a “editor,” which doesn’t really capture the signature genius she brought to the endeavor. Her last piece on the site, “President Rapist: Women Under Trump,” which ran on 3 December 2016, was a deconstruction of a photo taken two days after the election, in which First Lady Michelle Obama drinks tea with future First Lady Melania Trump—a moment otherwise lost in time:

These two women, Michelle and Melania, were at that moment, when that photo was taken, complicit in the overthrow. I’m not blaming them, especially not Michelle. I’m not going to trash Melania. But if we’re supposed to follow a model here, hers is dreadful. She has few apparent professional skills and appears to not have any facial expressions either: she is the chief representative of her husband’s favorite type: botoxed, girdled and owned, slender of thought and thigh.

Jana is a living, breathing fountainhead of creative ideas. A positive energy person—the sort it’s helped to have around these last three-plus years. She’s always super supportive of another writer’s work, and she was an early champion of PREVAIL.

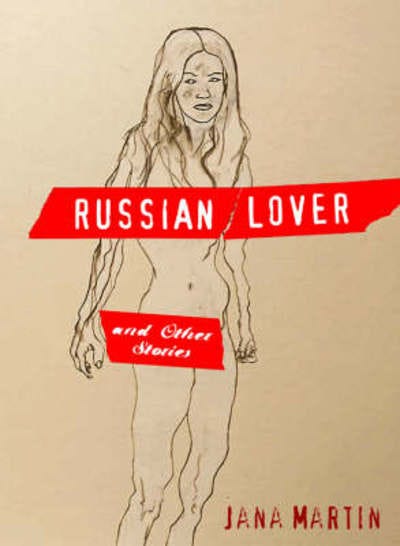

This is the end of a story called “Hope.” It’s from Jana’s book, called Russian Lover, which is not about Trump or Putin but is rather a collection of excellent short stories:

The end of “Hope”

In Brunswick, Georgia, the man sitting in front of me gets up his guff again. Here it comes. I’m sweating a pickle smell. His arm is pressing so hard into the bus seat that the cushion bawls like a calf. “Hey,” he says in a too-bright voice. “Here’s a question. What would you do if you were on a beach, say Miami Beach—”

“I’ve never been there,” I say. “That’s why I’m going.”

“Well, just wait. Just say you’re at any beach. They’re all this way. Debris washing up. Flotsam and jetsam. Probably more sam, right? I mean, Sam? I mean beaches these days, right? Some people will do just about anything on a beach.”

“All right,” I say, not wanting to get involved, and knowing the quickest way to end this is to cooperate. “I’m with you.”

“You’re walking,” he starts, “and you find a used condom in the sand.”

“What?”

“You’re walking, and you find a used rubber. A prophylactic.”

“I know what they are.”

“Well you’ve just found one on the beach.”

“Don’t people usually bury them?”

“Hey, I’m working out a theory here, so can I finish?”

“Sure,” I say.

“I mean there’s something about it, see?”

“Ugh.” I feel like acting the prude. My father would like that.

“No. I mean yes. Of course. But think. Consider this. There’s something about it. It’s got something in it.”

“Sure does,” I say.

“No. Wait. See you look at it, and you realize there’s something inside it that looks kind of like money. You realize it’s got money in it. A bill.”

“Not a chance,” I say. “How did it get there?”

“A fifty-dollar bill in it. You can see the numbers—Five. O.”

“Impossible,” I say.

“No, really. It’s got a big bill inside it. You don’t have any idea why. But there it is. Fifty smackeroos. Now. What do you do?”

“Oh,” I say. “That’s a hard one.”

“Well it was,” he laughs, “but probably not anymore. Anyway, what? Would you try to get it? Would you stick your fingers in there? Would you stick something else in there? Would you risk it?”

“That’s a tough one,” I say, stalling. He’s happy that he’s got my attention. He’s happy that he’s made me think. I wonder how long it took him to come up with the question. Maybe he rides buses days and nights and just thinks up things to ask people, feeling like he’s some sort of Grand Unsettler, his purpose in life being to shake out the truth. Maybe he heard the whole story in a bar. His eyes have that glint of someone who knows his question to be perfect and unanswerable. For him, I put a stumped look on my face. But I can only think of one answer, the only answer I really have.

See, safety is not really an issue for me anymore. It’s kind of a non-issue. It’s a one-way wall climbed over. I can’t climb back. It’s gloves on everyone’s hands when they have to touch me, sooner or later.

“Well,” I say. “It’s too late for me. It really is.”

“Right,” he says.

“I mean it. It wouldn’t matter.”

There’s a pause as my heart slows down and his heart speeds up. I know this. I’ve expected this. I mean, I haven’t told anyone, but I knew this is the way it would be.

“Hey,” he says, graven now, his bluish teeth ducking inside his dry lips. He settles back into his seat. “The fact has been recorded,” he says quietly. “I hear you, lady. Loud and clear. Ten-four. I hear you.”

His apology is kind of soothing—“And I’m sorry, I really am sorry”—over and over, until I’m on the brink of sleep.

He was the only one I would ever tell, I decided as my arm heated up. I pressed my cheek against the cool of the dark window for a distraction. Then I took the rest of the percosets so I wouldn’t scratch. Scratching is life, though, isn’t it? So I scratched. Then I was sure I was making indelible marks. I scratched because I was worried, then wished it were light so I could see if I had reason to worry. Not the overhead light, which I would’ve clicked on if I could disengage my nails from my arm long enough to reach up. Not that light. What a garish sight that might be, my battle-scarred arm in the reading light. Read bad shape, read mess, read old betadine. But if light filtered in from the outside, I decided, if it streamed in with the new day, I’d take that. I could look at nearly anything in that light.

Outside it was still dark and the bus still rumbled along. But there was a very slight cast to the outside, not even a color, just a lifting of the heaviest layer of dark. And still inside was all stale air and too-long sitting, all of us in here. The clumsy whisper sounds of heavy people shifting in the seats, the creak of the undercarriage, a baby letting out one cry, those children with their mother, pestering, “Why can’t we get off your lap, why can’t we get off the bus?” their hands yanking into her hair.

Finally it’s Orlando, and orange groves and horse farms. The bus takes me down this coast, traveling away from the freezing rain, the puritan looks on the T. I’m an escapee descending into nitrate canals, green lawns, unnameable birdflocks, the rays of new sun. In the lull of wheels and transmission shift and the slight seepage of carbon monoxide from the engine, just enough to soothe, I have made a list of all the jobs I am willing to take.

Waitress, pet-shop clerk, cage cleaner at a zoo, lunchbag stuffer for bad children at a center, ticket-taker at movies—sullen but glamorous in a dingy booth. There are so many wonderful things to do if only you imagine yourself a neophyte starlet, doe-eyed and ignorant of your own past twenty years. To have such little dreams takes serious revision, takes serious No, Dad, just let me get somewhere first and then I’ll get somewhere beyond it.

I will jerk orange juice into cone cups at a drugstore. I will dust off boxes of envelopes in the five-and-dime. I will time dental X-rays. I will rotate the chickens roasting on the supermarket rotisserie for the retirees to buy, so they can gum the soft meat and get some protein, which everybody needs.

My father will be proud of me. He will forget his tragic years and he will not be interested in the ways I have failed. He will not pry. He will just be proud of his blood and the way he upbrought me.

And me, when I land, I will not think of my father in the muckpond, tragically averting his own end, or those wool socks stretched by thieving feet, or the pant-less girls nodding out on my bed, Boyfriend looking at them puzzled, asking me, Can you get rid of her? I mean, I will remember. But there will be something else, more simply spelled out and drawn in brighter colors, like a primer on how to grow up, with words like food, house, money, job. We’re taught well, don’t you see, when we’re still young. Think of those black-lettered words next to the happy pictures. If we only knew how to obey them. See Spot run. See Hope try.

We’re ready to live our way right out of kindergarten. But we have to wait for everyone else to step aside, and don’t you know it, they don’t always. Or they step aside so far that they land in an entirely different country, and how can you take their place? I’m not making excuses. I’m not blaming bad Boyfriend, or the tancoat down the street with his little dimebags of boric mindsquawk, and certainly not my father, alone with the quartet, as I crawled up the calico wallpaper in my Massachusetts bedroom.

Here I am, a girl on a bus. My eyes are getting used to this subtropical glare, this mega-light. Oh, what a diet this light must be. The trees whoosh with joy and rattle their fronds at the sky. White birds have tracked us for miles now, attracted to the bus’s silver back. Here you can appreciate the shape of buses, their long, shiny sweep of brilliant tin, that running dog on the side stretching his legs far as he can. I am heading for the land of smocks and weekly wages, for the land of swimming pools. I am heading for the land of paper bags for kids with sunburned noses and grubby hands.

My father, I’m sure, will make up a nice story about me. She is on her way to a teaching certificate. She is learning how to run a nursery school. She was always fond of children, my daughter. Always understood them, she felt. Good man. My father, the cardigan innocent, sustained on Quaker Oats.

Looking at the orange groves, the grazing horses, the snug buildings and little people here and there, the floral, chemical scents leaking through the vents, I vow to find my father a sweet wife. That’s what he needs. It’s been long enough. I don’t know if I’ll ever want the icy air again, or if I’ll miss that bleak northern city. And my father, he needs someone. A woman rooted so tightly to the earth that her way of being upset is to make a giant ham, stick pineapple rings on its sides like big bug eyes, and to weep like a collie over the glaze.

Jana Martin (@lunchvintage) grew up in New Jersey, Boston, and New York City, graduated from Oberlin College, and received an M.F.A. from the University of Arizona. Her story “Hope” (included in this collection) won a Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers. Jana’s stories have also appeared in Five Points, Spork, Willow Springs, Yeti, and other journals; her nonfiction has been published in the Village Voice, Marie Claire, and Cosmopolitan. She live in Woodstock, NY, where in her spare time she is learning search and rescue with her dog Lee.

"President Rapist: Women Under Trump" is an excellent post that is just as apt//disconcerting today as when it was written. Thanks for the introduction to another fine author, Greg Olear. It says in that post's bio of Jana Martin that she is writing a book on wolves. Would be very interested in an excerpt from that if she's willing to share.