Dear Reader,

We die twice: once when we actually die, and a second time when the memory of us fades away. There is no funeral the second time, no eulogy, no tears. There is permanent erasure—extinction, if you prefer, which is the English translation of the Sanskrit word nirvana.

This is not my idea. I read it somewhere, long ago, and—appropriately, given the subject of memory—I can’t recall where I read it or who wrote it. The idea is both poetical and objectively true. There will come a time, for all of us, when every last trace of our existence will be wiped away. We will quite literally be lost.

Given enough time, even the most famous and consequential among us are distilled to a sentence, a phrase, a single word: Napoleon was a short general who tried to invade Russia in winter. Henry VIII was a fat king with many wives. Joan of Arc was burned at the stake. Julius Caesar was stabbed in the back on the Ides of March. The Buddha sat under a tree and found enlightenment. Et cetera.

Memory is for the living. Legacy is for the living. The dead don’t require homage, not really. But part of being human is to want to preserve the memory of our loved ones: to honor the ancestors. That impulse is the foundation of art, of architecture, of poetry.

After the Great War, the poet Giuseppe Ungaretti—a formidable figure in the annals of Italian literature, who was associated with Futurism, Dadaism, and Hermeticism—hooked up with Benito Mussolini. He was a correspondent for Mussolini’s newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia. He signed the Manifesto of Italian Writers in 1925. He saw Fascism as a vehicle for restoring the prominence of Italian art: “The first task of the Academy will be to re-establish a certain connection between men of letters, between writers, teachers, publicists. This people hungers for poetry. If it had not been for the miracle of the Blackshirts, we would never have leaped this far.” In other words, he believed Benito would Make Italy Great Again.

Ungaretti joined the Fascist Party. He worked for the Fascist regime. He even lobbied for Il Duce to write an introduction to one of his poetry books: “Would H.E. [His Excellency], who is consecrating renewed Italianity, raise my faith? I address H.E. as a Renaissance man; when Italy was great in the world, the powerful would not disdain to crown her with beauty (which is the only immortality). A few lines of preface from H.E., whenever the grave State affairs will allow you a moment of repose, would for me, in the eyes of all, be a great honor.” And he left behind letters in which he expressed racist, anti-Semitic, and anti-Arab sentiments.

But in September of 1916, in a foxhole at Locvizza, the 28-year-old poet managed to transcend all of that ugliness to produce a lovely, haunting poem called “In Memoriam.” Ungaretti had been living in Paris in a shitty hostel a few blocks from the Sorbonne. There he befriended one of the other residents, a fellow poet and foreigner, Mohammed Sceab, who had taken his own life in 1913. In that foxhole three years later, with death hanging in the air, Ungaretti the solider was consumed by the fear that his own expiration might also ensure the final death of his friend. And so he wrote a poem.

I don’t speak Italian, but the language here is so simple, it’s not that hard to understand the lines. I will put the English translation below each stanza:

Si chiamava

Moammed Sceab

discendente

di emiri di nomadi

suicida

perchè non aveva più

Patria.His name was

Mohammed Sceab

descendant

of emirs of the nomads

a suicide

because he no longer had

a homeland

Amò la Francia

e mutò nome

Fu Marcel

ma non era Francese

e non sapeva più vivere

nella tenda dei suoi

dove si ascolta la cantilena

del Corano

gustando un caffèHe loved France

and changed his name

He was Marcel

but was not French

and he no longer knew

how to live

in the tents of his people

where they listen to the chant

of the Koran

while savoring coffee

E non sapeva

scioglere

il canto

del suo abbandonoAnd he did not know how

to unfreeze

the song

of his cold desolation

L’ho accompagnato

insieme alla padrona dell’ albergo

dove abitavamo

a Parigi

dal numero 5 della rue des Carmes

appassito vicolo in discesa

I accompanied him

together with the landlady of the hotel

where we lived

in Paris

at number 5 rue des Carmes

a crooked dark alley

Riposa nel camposanto d’Ivry

sobborgo che pare

sempre in una giornata

di una

decomposta fieraHe rests in the graveyard at Ivry

a suburb that always

looks like the day

the carnival

comes downE forse io solo

se ancora

che visseAnd perhaps only I

still know

he lived

I think of Ungaretti’s poem today, and recall the poet’s love for his long-gone friend Mohammed. And I think of Mohammed’s desolation, his inability to integrate into a new environment, the profound sadness at his loss, as I look at images from the devastation in Asheville and throughout Appalachia.

This is not the typical coastal destruction (which itself is horrible enough and should not be minimized). This is different. Vast seas of water drained from the mountains into the valleys where the people live, churning up mud and debris as it poured down with astonishing power. Small towns have been completely destroyed. There is no power, no water, no cell service—and no way out. All of the Interstate highways into and out of Asheville were damaged by the storm. From where I sit, the destruction looks apocalyptic. Biblical. How can we witness such a great flood and not contemplate the wrath of God?

Is the devastation in Appalachia a metaphor? A foreshadowing? Divine retribution? Quirk of fate? I found myself, shamefully, wondering how it might affect the election—whether it will help Kamala or hurt her.

We have, as a people, normalized the damage caused by hurricanes and other natural disasters. On the New York Times website this morning, the little section about “Helene Aftermath” is well below the jump, right next to a section about Paris Fashion Week; the editors believe that the escalating atrocities in the Middle East—which, as many of the social media posts about Appalachia are quick to point out, the United States government is underwriting while ignoring more exigent needs at home—are more newsworthy. (The abominable war crimes in Kherson, meanwhile, are not being reported on at all.)

At a rally in Michigan, Trump correctly noted, as he read stolidly off the Teleprompter, that Helene “was a very large hurricane—that was a big one.” He said, without much conviction or interest in his voice, that people in its path would “be okay.” This is the same guy who threw paper towels at hurricane victims in Puerto Rico, mind you. His re-election would doom our democracy, and might also doom human life on earth, given his ignorance of and lack of interest in climate change, as well as his eagerness to whore himself out to the fossil fuel industry.

Will the wordsmith who gave us Hillbilly Elegy also write the hillbilly eulogy? JD Vance is a fascist like Ungaretti, but unlike Ungaretti, lacks the requisite empathy and compassion to give a crap. He is “skeptical of the idea that climate change is caused purely by man,” or so he claims. If he’s telling the truth, he’s intellectually unfit for office. And if he’s lying, as I suspect he is, well, that’s even worse.

It’s tempting to exploit these extreme weather tragedies for political purposes. I did it myself, on Friday’s show, railing against the GOP’s willful ignorance of climate change. And I did it again just now, because I am living in a place that is safe and dry, where the highways are accessible and the WiFi still works.

Meanwhile, the hurricane victims in Appalachia suffer, off the national radar, off the front page—nomads now, singing their own songs of cold desolation. We must keep alive the memory of what happened there.

I write this today to make sure that I myself do not forget.

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Alyssa Bowen of True North Research:

And we did this. Thanks to Stephanie St. John for the killer Melania impression:

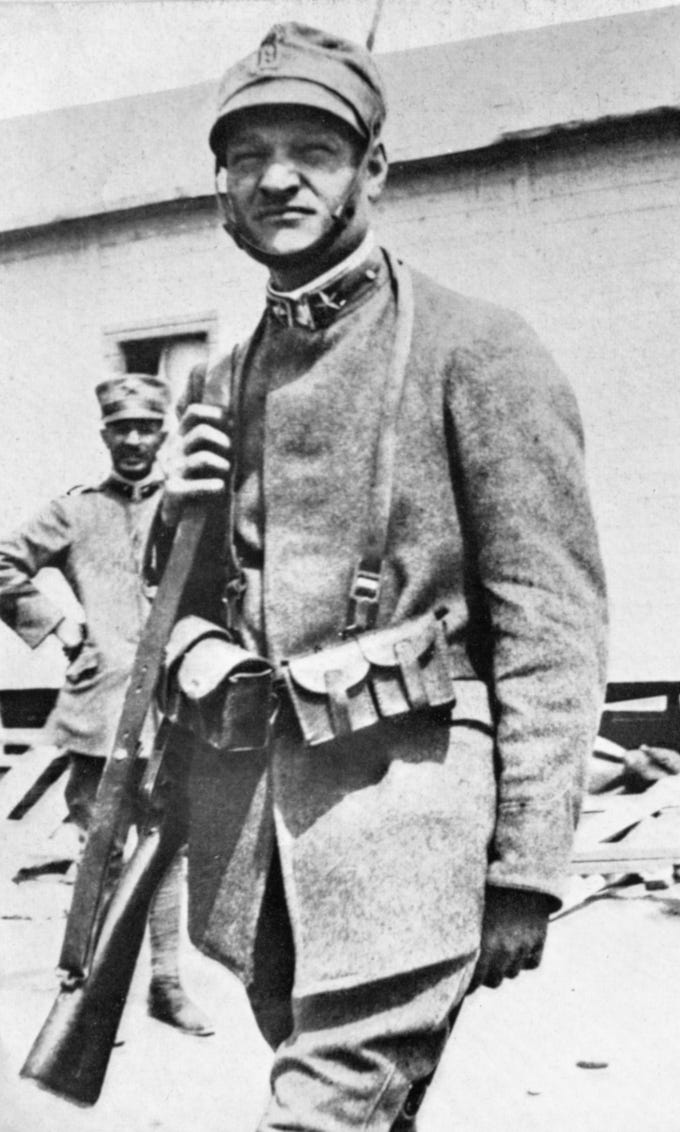

Photo credit: Ungaretti in Italian infantry uniform during World War I.

So true. At 87 I probably am the only human who thinks about my dear Mom, Dad, and other departeds who were once so lively. They still live in my heart.

So brief our stay here, and so much joy, pain, good and evil. We writers try to leave tracks in the sands of time.

In vain. Eons on our species may wear God out and he will let us lapse. Our planets consumed. Our voices stilled.

So I rejoice in the now. Tomorrow we may be swept away. Billserle.com

Great thoughtful post

Banksy, "They say you die twice. One time when you stop breathing, and a second time when somebody says your name for the last time."

I also saw this attributed to Ernest Hemingway when I googled. And it’s so true.

Me being a childless cat and dog lady, I figure when my one niece, I’m in contact with, is gone and her two children are gone…I’ll be gone for good.