Dear Reader,

One of the wonderful virtues of owning books is that, as physical objects that adorn your shelves and not pixels on some flickering electronic device, they stand and wait, always at the ready, like spices in a rack. We never know when we may be inspired to pick one up, read through it, and extract from it the wisdom bound, literally bound, within its pages.

Thirty some-odd years ago, I bought a copy of An Age Like This, the first volume of George Orwell’s collected essays, journalism, and letters, covering the period 1920-1940. Back in 1996 or so, I read the first few pages, got bored, and placed the book on my shelf, where it sat gathering dust until this week, when the great librarian of intuition pushed it into my lap.

Orwell’s contemporary writings in the early days of the Second World War, irrelevant to me in my early twenties during the Clinton Administration, have, in the first few days of 2025, become exigent, urgent, vital. Here is one of the most prescient novelists of the twentieth century, an ardent anti-Fascist, revealing some of his thought processes in the years before writing Nineteen Eighty-Four, arguably the most important work of fiction of the last hundred years.

In 1940, Orwell published a long essay called “Inside the Whale,” ostensibly an examination of the unexpected new direction English literature had taken while Hitler and Stalin were busy consolidating their power and, in so doing, imposing aesthetic restrictions on writers and artists. A lot of authors are discussed in the essay, but the main focus is Tropic of Cancer, the controversial novel by Henry Miller that was denounced as pornography when Obelisk Press published the first edition in 1934, and widely banned. (Want to read banned books? This is the book most banned! Not only that, but this is the book which illicit sale generated the ruling in Grove Press v. Gerstein that struck down book bans!) Indeed, Orwell’s own copy of Tropic of Cancer was seized by British authorities in January 1940. As he writes to his friend and publisher Victor Gollancz, “two detectives suddenly arrived at my house with orders from the public prosecutor to seize all books which I had ‘received through the post,’” adding, with no little irony, “The police were only carrying out orders and were very nice about it.”

Curiously, I read Tropic of Cancer right around the time that I bought An Age Like This, oblivious to the fact that the latter contained an essay about the former. I quite liked it. Miller, it seemed to me, was living the sort of life the Beat writers, who I detest, aspired to live, claimed to live, but were not authentically living. (Like, for most of his life, Kerouac that big rebel lived with his mom.) Henry Miller was a literary party crasher. He was metal. I admired his ambition, his commitment to his art, his free spirit, his sense of adventure. (As far as adventure goes, I was, and am, a careful guy, more comfortable with the Kerouac living-with-mom attitude than Miller’s devil-may-care drunken Parisian poverty.) I liked that he took himself and his work seriously. I liked that he demanded attention—but not in the plastic, surface way that, say, a TikTok influencer demands our attention.

This, the third paragraph of the book, is a nice example of the “mad gaiety,” as Anaïs Nin puts it in her foreword to the novel, of his proclamatory style:

Boris has just given me a summary of his views. He is a weather prophet. The weather will continue bad, he says. There will be more calamities, more death, more despair. Not the slightest indication of a change anywhere. The cancer of time is eating us away. Our heroes have killed themselves, or are killing themselves. The hero, then, is not Time, but Timelessness. We must get in step, a lock step, toward the prison of death. There is no escape. The weather will not change.

I have tried a few times since to re-read Tropic of Cancer, but can’t get past the first two chapters. It’s too scattered, too haphazard, too precious, while at the same time being all about him. Nothing really happens, and a lot of his artistic pretensions are just that: pretentious. Although it teems with sexual vivacity—Henry Miller was a horny old goat—it is not particularly good pornography, or even good erotica. Miller is misogynistic, antisemitic, irresponsible, narcissistic, kind of an asshole, and a huge troll. One might even call him “Trumpy.” But in 1934, his approach was revolutionary. Miller stampeded into the literary temple like an angry, profane bull and rammed his horns into the tables of the critics, overturning everything.

Orwell’s sensibilities were hardly in “lock step,” as it were, with those of his contemporaries; he was sui generis. Even so, he was not at all like Henry Miller. Eric Blair was a man plugged into the wider world: Burma, India, Catalonia, the seedier parts of Paris and London, and also Eton, where he was taught French by Aldous Huxley. (Quel meilleur des mondes cela a dû être!) Miller, by contrast, was a world unto himself, seemingly impervious to the global goings-on around him.

While reading Tropic of Cancer, Orwell is made acutely aware of this difference of approach. “Inside the Whale” is, basically, his attempt to reconcile his critical admiration for the novel—which is not, as he puts it, “a bit of naughty-naughty leftover from the ‘twenties…but a very remarkable book”—and his personal disdain for the passive attitude of its author. He writes:

When Tropic of Cancer was published the Italians were marching into Abyssinia and Hitler’s concentration camps were already bulging. The intellectual foci of the world were Rome, Moscow and Berlin. It did not seem to be a moment at which a novel of outstanding value was likely to be written about American dead-beats cadging drunks in the Latin Quarter. Of course a novelist is not obliged to write directly about contemporary history, but a novelist who simply disregards the major public events of the moment is generally either a footler or a plain idiot.

A footler is one who footles: that is, a time-waster, a fritterer, a ditherer. Orwell recognizes that Miller is neither footler nor idiot, but struggles to comprehend him:

Miller’s outlook is deeply akin to that of Whitman, and nearly everyone who has read him has remarked on this. Tropic of Cancer ends with an especially Whitmanesque passage, in which, after the lecheries, the swindles, the fights, the drinking bouts and the imbecilities, he simply sits down and watches the Seine flowing past, in a sort of mystical acceptance of the thing-as-it-is. Only, what is he accepting? …[N]ot an epoch of expansion and liberty, but an epoch of fear, tyranny and regimentation. To say “I accept” in an age like our own is to say that you accept concentration camps, rubber truncheons, Hitler, Stalin, bombs, aeroplanes, tinned food, machine-guns, putsches, purges, slogans, Bedaux belts, gas-masks, submarines, spies, provocateurs, press censorship, secret prisons, aspirins, Hollywood films and political murders. Not only those things, of course, but those things among others. And on the whole that is Henry Miller’s attitude.

That sort of passive acceptance—what therapists might today call “radical acceptance”—may have been excusable in the nineteenth century, when Whitman plied his poetic trade, but, Orwell suggests, is morally irresponsible if not reprehensible in the totalitarian thirties:

But unquestionably our own age, at any rate in Western Europe, is less healthy and less hopeful than the age in which Whitman was writing. Unlike Whitman, we live in a shrinking world. The “democratic vistas” have ended in barbed wire. There is less feeling of creation and growth, less and less emphasis on the cradle, endlessly rocking, more and more emphasis on the teapot, endlessly stewing. To accept civilization as it is practically means accepting decay. It has ceased to be a strenuous attitude and become a passive attitude—even “decadent”, if that word means anything.

Orwell is not basing his opinion solely on the text of Tropic of Cancer. Eric Blair knew Henry Miller well enough to have dinner with him in Paris a few days before Christmas 1936. He was on his way to Spain, where he planned to cover the civil war—the original anti-Fascist battle of the twentieth century:

What most intrigued me about [Miller] was to find that he felt no interest in the Spanish war whatever. He merely told me in forcible terms that to go to Spain at that moment was the act of an idiot. He could understand anyone going there from purely selfish motives, out of curiosity, for instance, but to mix oneself up in such things from a sense of obligation was sheer stupidity. In any case my ideas about combating Fascism, defending democracy, etc etc were all boloney. Our civilisation was destined to be swept away and replaced by something so different that we should scarcely regard it as human—a prospect that did not bother him, he said. And some such outlook is implicit throughout his work. Everywhere there is the sense of the approaching cataclysm, and almost everywhere the implied belief that it doesn’t matter.

This is, I think, a spot-on reading of Tropic of Cancer. Miller’s original choice of title was Crazy Cock—yuck—but a better one might have been: Atlas Shrugged at the Approaching Cataclysm. The prevailing obscenity laws prevented Orwell from quoting from the book to show what he meant, but I don’t have such prim limitations. Here is one such passage:

The world around me is dissolving, leaving here and there spots of time. The world is a cancer eating itself away...I am thinking that when the great silence descends upon all and everywhere music will at last triumph. When into the womb of time everything is again withdrawn chaos will be restored and chaos is the score upon which reality is written. You, Tania, are my chaos.

And this:

You are the sieve through which my anarchy strains, resolves itself into words. Behind the word is chaos. Each word a stripe, a bar, but there are not and never will be enough bars to make the mesh.

And finally, this bit of shiny happy fun:

For a hundred years or more the world, our world, has been dying. And not one man, in these last hundred years or so, has been crazy enough to put a bomb up the asshole of creation and set it off. The world is rotting away, dying piece meal. But it needs the coup de grâce, it needs to be blown to smithereens.

That last excerpt calls to mind another piece of writing, from half a century later:

It will be objected that the French and Russian Revolutions were failures. But most revolutions have two goals. One is to destroy an old form of society and the other is to set up the new form of society envisioned by the revolutionaries. The French and Russian revolutionaries failed (fortunately!) to create the new kind of society of which they dreamed, but they were quite successful in destroying the old society.

That’s a passage from Industrial Society and Its Future, otherwise known as the Unabomber Manifesto—the seminal text of the neo-reactionary Dark Enlightenment.

A shorter word for “the implied belief that [the coming cataclysm] doesn’t matter” is nihilism. Miller was damn sure familiar with the word and the philosophy. The term was first popularized by Ivan Turgenev in his 1862 novel Fathers and Sons; early in Tropic of Cancer, on page eleven in my copy, Miller extols “the perfection of Turgenev.” Here is the (nihilistic) paragraph that follows:

There is only one thing which interests me vitally now, and that is the recording of all that which is omitted in books. Nobody, so far as I can see, is making use of those elements in the air which give direction and motivation to our lives. Only the killers seem to be extracting from life some satisfactory measure of what they’re putting into it. The age demands violence, but we are getting only abortive explosions. Revolutions are nipped in the bud, or else succeed too quickly. Passion is quickly exhausted. Men fall back on ideas, comme d’habitude. Nothing is proposed that can last more than twenty-four hours. We are giving we are living a million lives in the space of a generation.

That’s rousing stuff, to be sure. But it is neither left nor right. It could be comfortably inserted into a Luigi Mangione manifesto or a pre-J6 speech by Alex Jones. There’s no political bent to nihilism.

All of this après moi, le déluge stuff is anathema to Orwell, who does believe in something (democratic, which is to say real, socialism; neither the Nazi nor Soviet variety). In “Inside the Whale,” he writes about the “debunking of western civilisation” that reached a fever pitch in the affluent twenties, with the result, by 1940, of a disillusioned generation hungry for purpose and meaning. “Patriotism, religion, the Empire, the family, the sanctity of marriage, the Old School Tie, birth, breeding, honour, discipline—anyone of ordinary education could turn the whole lot of them inside out in three minutes. But what do you achieve, after all, by getting rid of such primal things as patriotism and religion? You have not necessarily got rid of the need for something to believe in.” Yes! Exactly that!

If this nihilistic disillusionment was acutely felt in the thirties, before Google and social media, when the laughably benign Tropic of Cancer was considered so obscene as to be pornographic, what of now, when Western civilization is not so much debunked as drowning in content? We may believe in the same things Orwell believed in: democracy, anti-Fascism, human rights, the rule of law. But at the moment, our politicians, our media figures, our celebrities, our plutocrats—our leaders; not all of them, of course, but far too many—seem unconcerned with any of this, seem blithely ignorant of the grim reality of our plight. We are believers abandoned by our gods.

What to do about that? Where to find our purpose and meaning? Or, rather, how to best nurture, best harness, and best direct our purpose and meaning, to achieve the desired result? A thousand violins playing at once demands a conductor!

This spiritual struggle is not peculiar to anti-fascists. Orwell notes that many writers of a hundred years ago took to Catholicism, seeking purpose and meaning in the oldest and most mystical Christian church. This is interesting when we consider that Catholicism is today popular among the aforementioned Dark Enlightenment set, and that a reactionary, Opus Dei-flavored strain of that religion commands much power in the halls of justice. (During the McCarthy hearings Jack Kerouac, one generation removed from Miller, got stoned and cheered for the bad guys; the King of the Beats was a staunch Catholic who painted a portrait of the Nazi-loving Pope Pius XII and hung it in his home.)

The two great midcentury novelists are responding to the same world problems, reacting to the same cultural and geopolitical stimuli, but in diametrically opposite ways—although Henry Miller is not, on the surface, much concerned about any of it. He loathes everything, not least the country of his birth, but he doesn’t let it get to him. “America,” he writes, in one of the more hyperbolic proclamations in Tropic of Cancer, “is the very incarnation of doom. She will drag the whole world down to the bottomless pit.” Orwell’s strong convictions Miller sees as—and because Orwell uses the word “idiot” twice in the essay, I’m guessing this is an exact quote—idiotic.

The feelings are perhaps not reciprocal. Orwell writes:

At this date it hardly even needs a war to bring home to us the disintegration of our society and the increasing helplessness of all decent people. It is for this reason that I think that the passive, non-cooperative attitude implied in Henry Miller’s work is justified. Whether or not it is an expression of what people ought to feel, it probably comes somewhere near to expressing what they do feel.

The disintegration of our society and the increasing helplessness of all decent people come part and parcel with the establishment of a different society (cut to the Unabomber, smiling) and the increasing power-consolidation of all the assholes (cut to Elon Musk, failing to smile like a normal human). Not nineteen eighty-four but twenty twenty-five. Is there not, among us decent people, a tropism toward passivity, if not advance surrender, in these dark times? Is this not how we feel, with the second Trump inauguration looming, just two weeks away? Don’t we want to curl into the fetal position and bury ourselves in blankets on the couch? Or is that just me?

And so what if it is? Going numb is not the same as obeying. Non-cooperation is not collaboration. Or, as the Gen X filmmaker Richard Linklater put it back in the Slacker nineties, “Withdrawal in disgust is not the same as apathy.”

This inner conflict, I think, is what Orwell grapples with in “Inside the Whale.” He wants somehow to be active and passive at the same time. Perhaps that ambiguity is what makes conservatives and liberals both claim him as one of their own?

The title of Orwell’s long essay derives from a piece Henry Miller wrote about the diaries of Anaïs Nin, in which he compares his friend and lover to Jonah in the belly of the whale, and goes on to suggest that, all things considered, there are worse places to be. (Florida, maybe? Or the Bronx?)

“The whale’s belly,” Orwell explains, “is simply a womb big enough for an adult.” He continues:

There you are, in the dark, cushioned space that exactly fits you, with yards of blubber between yourself and reality, able to keep up an attitude of the completest indifference, no matter what happens. A storm that would sink all the battleships in the world would hardly reach you as an echo. Even the whale’s own movements would probably be imperceptible to you. He might be wallowing among the surface waves or shooting down the blackness of the middle seas (a mile deep, according to Herman Melville), but you would never notice the difference. Short of being dead, it is the final, unsurpassable stage of irresponsibility….

We detect a hint of wistfulness that almost approaches envy when Orwell laments that, without a doubt, “Miller himself is inside the whale.” It’s a see-through whale, and it probably has a stripper pole running down from the blowhole, and certainly a full bar, but it’s a big fishy safe space just the same. Orwell marvels at the fact that Miller “feels no impulse to alter or control the process that he is undergoing. He has performed the essential Jonah act of allowing himself to be swallowed, remaining passive, accepting.”

Nice to stop swimming against the current and give in. But give in to what? Soviets and Nazis? Concentration camps? Great famines? And, further, what is the writer’s duty at such a moment? Fascism is based on lies, after all, and fiction, while made-up, is based on truth. Is there—can there even be—a literature of totalitarianism? Orwell writes:

Almost certainly we are moving into an age of totalitarian dictatorships—an age in which the freedom of thought will be at first a deadly sin and later on a meaningless abstraction. The autonomous individual is going to be stamped out of existence. But this means that literature, and the form in which we know it, must suffer at least a temporary death. The literature of liberalism is coming to an end and the literature of totalitarianism has not yet appeared and is barely imaginable. As for the writer, he is sitting on a melting iceberg; he is merely an anachronism, a hangover from the bourgeois age, as surely doomed is the hippopotamus. Miller seems to be a man out of the common because he saw and proclaimed this fact a long while before most of his contemporaries—at a time, indeed, when many of them were actually burbling about a renaissance of literature….

And lo, smack dab on the first page of Tropic of Cancer, as if to end the suspense, Miller declares, “Everything that was literature has fallen from me. There are no more books to be written, thank God.”

The beginning of Tropic of Cancer brings us to the end of “Inside the Whale”—the passage that has the most relevance to the here and now. We decent people are all, I think, struggling to come to terms with the impending Trump Redux. We’ve memorized our Timothy Snyder rules, we’ve leaned on each other more, we’ve deleted social media apps and canceled legacy media subscriptions and turned off the cable news shows. But ultimately we are trying to solve the same puzzle that, for a good long while, stumped George Fucking Orwell. In this passage, he has synthesized the two ideas: the active defense of freedom and the passive acceptance of tyranny. He’s almost there:

It seems likely, therefore, that in the remaining years of free speech any novel worth reading will follow more or less along the lines that Miller has followed—I do not mean in technique or subject-matter, but in implied outlook. The passive outlook will come back, and it will be more consciously passive than before. Progress and reaction have both turned out to be swindles. Seemingly there is nothing left but quietism—robbing reality of its terrors by simply submitting to it. Get inside the whale—or rather, admit that you are inside the whale (for you are, of course). Give yourself over to the world-process, stop fighting against it or pretending that you control it; simply accept it, endure it, record it. That seems to be the formula that any sensitive novelist is now likely to adopt. A novel on more positive, “constructive” lines, and not emotionally spurious, is at present very difficult to imagine.

Orwell finished “Inside the Whale” in 1940. By the time Nineteen Eighty-Four is published, nine years later, he’s cracked the code. He’s figured out how to be both active and passive in his fiction, and even, perhaps, glimpsed how literature can be both liberalistic and totalitarian. To understand this, we need only look at how he ends his last and greatest literary work:

Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose. But it was alright, everything was alright, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.

That is Winston Smith—finally! after forty years of inner struggle!—allowing the great cetacean to swallow him up. He has gone the way of Henry Miller. At long last, he is inside the whale!

(It’s hard to read the antepenultimate line and not think of Joe Biden, in his flaccid speech after the election, insisting that “we’re going to be okay.”)

Ah, but Nineteen Eighty-Four does not end with the story of Winston Smith. The last pages of the book are a curious appendix, “The Principles of Newspeak,” which reads not unlike the other essays in An Age Like This. This is a faux scholarly text, an analysis of what the Party was trying to achieve with its modifications to the English language: “The purpose of Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees of Ingsoc, but to make all other modes of thought impossible.”

The firehose-of-shit, accuse-them-of-what-we-do strategy pioneered by Joseph Goebbels and employed by Steve Bannon, by Donald Trump, by Stephen Miller, by Speaker Mike Johnson, by Elon Musk, has, I think, the same aim. By appropriating the very words we need to articulate their crimes, the MAGA are trying to make it impossible for us to call them out. They have linguistically neutered our denunciations. They call Hillary Clinton a pedophile, which is a vile lie; but it has the affect of making the word pedophile meaningless, so when an actual pedophile comes along, and is almost invariably a MAGA Republican, the label has all the power of “I know you are but what am I.” We can’t call what Trump did with the Russians collusion, because he has blown that word apart. Any honest attempt to audit the election results will necessitate the use of terms like rigging and cheating and stolen, and the Trumpists have used them so much as to drain them of all literality. And, sadly, we have compared so many people to Hitler, and spoken so often of Nazis, that Trump’s own, very real Hitlerian tendencies are largely ignored by the press, and real Nazis have come from Germany to kiss the ring at Mar-a-Lago with impunity.

The thing is, this doesn’t work. The Bannon-Goebbels strategy is doomed to failure. Boris the Tropic of Cancer weather prophet is wrong; the weather does change. The path of the Seine is not, pace Miller, permanently fixed. That’s Orwell’s message in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

The existence of the appendix tells us that the totalitarian state described in the novel did not last. Ingsoc, or English Socialism, collapsed. Big Brother fell—and much sooner than anyone expected. Context clues in “The Principles of Newspeak” (the eleventh edition) suggest that it was released at least a decade after 1984, but before the first two decades of the twenty-first century, when the Newspeak translations of Dickens, Milton, and Shakespeare were slated to be completed—so around 1995, when the Washington Post published Ted Kaczynski’s Industrial Society and Its Future and Richard Linklater was talking about withdrawal in disgust. That means the (fictitious) “Principles of Newspeak” came out about the same year that I bought (for real) my copy of An Age Like This.

Jonah may be trapped inside the whale, but he doesn’t remain there. At the command of God, the big fish vomits him out. He then goes to Nineveh, and warns the citizens that the city is toast in forty days unless they clean up their act, which they do.

So: he is passive, as passive as can be, gathering his strength; and then he is active, as active as can be, using his strength; and this is how he saves the people who, as the Lord puts it, “cannot discern between their right hand and their left.”

Peace is antithetical to war, slavery is not freedom, and there is no strength, none, in ignorance.

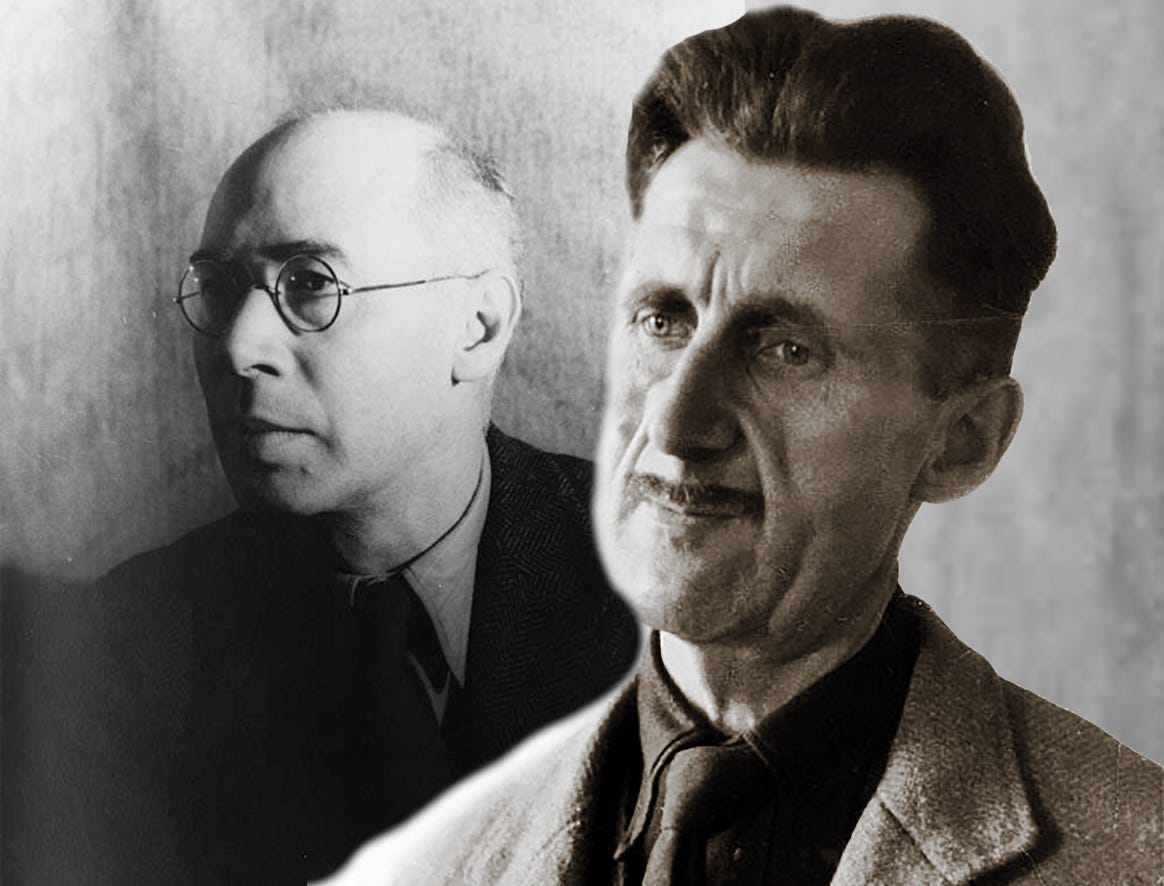

Photo credit: Henry Miller, ca. 1940, Carl Van Vechten photograph collection (Library of Congress). George Orwell, ca. 1949, from Flickr, Levan Ramishvili.

Nixon was inaugurated for his second term in January of 1973. He had won with 60% of the popular vote and taken the electoral college votes of forty nine states. Trump isn’t close to that margin of victory or that kind of power. By August of 1974 tricky dickie was forced to resign when it became clear that he had cheated. It took just over eighteen months for him to fall.

The weather will change, it always does.

Well that was really well done. I'm keeping this one. Thank you for bringing thought-food to the table once again!