Dear Reader,

Today is my parents’ 51st wedding anniversary, which is easy for me to remember, coming as it does on D-Day. Last year, then, was their 50th anniversary—a big deal. Normally we would have had a party to mark the milestone, but because of the pandemic, none of the stops could be pulled out. That celebration was one of countless events denied us this past year-and-a-half, a casualty of the coronavirus.

Needless to say, in the grand scheme of things, missing an anniversary party is nothing. Everyone on the planet has a story like this, and most have far worse ones to tell. It’s not just that people died, but the way the dying had to perish in isolation, separated from their loved ones. It’s the lack of proper funeral gatherings, the insufficient mourning.

Mary Flood, my late grandmother’s cousin, was the sort of person who came to your house whenever someone died with a plate of food. She was active in the Church. She was at the wakes, at the funerals, she checked in with you afterwards. She was almost an Angel of Death, because whenever someone passed, there she was, like an angel, to care for you. Mary died this past January, of coronavirus complications. It was late enough in the pandemic where they were able to have a funeral mass, but only her immediate family could attend. Every Italian in Morris County would have come to pay their respects, but no, not in a Plague Year. I watched the service on Zoom, her grieving son, the empty pews, the remarkably crisp image arriving like a miracle on my monitor, and I cried—not at her loss, but at the unfairness of it all. This was a woman who deserved better.

And now, 51 years to the day that my parents tied the knot, and 77 years to the day that Allied forces stormed the beaches at Normandy, we once again can gather. We can break bread with our friends and extended family. We can hug. We can toast the newlyweds at wedding receptions and honor the dead at funerals. It is a small thing, but it is everything. And it is something to celebrate.

Daniel Defoe was one of the first novelists writing in the English language, and also one of the first to deliberately blur the line between fact and fiction. Robinson Crusoe, that early 18th century Castaway, draws heavily from the journals of shipwrecked Scotsman Alexander Selkirk. Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year (pub. 1722) is essentially a memoir, as every major detail cited in the work is verifiably true. Only, Defoe was five years old in 1665, during the Great Plague of London; the “fiction” here is that he is pretending to be his uncle, Henry Foe. There was then, and is still now, argument over how the book should be classified.

Journal of a Plague Year is cited in the introduction to Nina Burleigh’s excellent new book, Virus: Vaccinations, the CDC, and the Hijacking of America’s Response to the Pandemic. She re-read Defoe at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, and returned to it periodically. She was struck by how little things have changed:

Everything, from the nature of and response to the early rumors to the growing sense of unease and the closing of houses of entertainment, from the quack cures and conspiracy theories to the rich fleeing the city and the poor dying in it, from mental health breaking down and mad, cooped-up people breaking free of quarantine and roaming the streets in violation of curfews and sanitary rules—all of it. Just like us.

I had a similar inkling to read Plague Year, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I didn’t have the emotional bandwidth. Only now, 18 months after the first outbreak in Wuhan, do I crack open my copy of the book—not to absorb the whole thing, as Nina did, but to do what Defoe’s uncle could not: skip right to the end.

The difference between London in 1665 and New York in 2021 is that we have doctors and scientists who created a vaccine, and a president in Joe Biden who helped vaccinate a large population in a short period of time. It was a triumph of mankind. Poor Daniel Defoe just had to wait for God’s wrath to burn itself out. Indeed, the Great Plague of London ended just as the Former Guy predicted the covid-19 pandemic would: one day, like a miracle, it just disappeared.

For today’s “Sunday Pages,” here is the end of Defoe’s work of sort-of fiction:

In the middle of their distress, when the condition of the city of London was so truly calamitous, just then it pleased God—as it were by His immediate hand to disarm this enemy; the poison was taken out of the sting. It was wonderful; even the physicians themselves were surprised at it. Wherever they visited they found their patients better; either they had sweated kindly, or the tumors were broke, or the carbuncles went down and the inflammations round them changed color, or the fever was gone, or the violent headache was assuaged, or some good symptom was in the case; so that in a few days everybody was recovering, whole families that were infected and down, that had ministers praying with them, and expected death every hour, were revived and healed, and none died at all out of them.

Nor was this by any new medicine found out, or new method of cure discovered, or by any experience in the operation which the physicians or surgeons attained to; but it was evidently from the secret invisible hand of Him that had at first sent this disease as a judgment upon us; and let the atheistic part of mankind call my saying what they please, it is no enthusiasm; it was acknowledged at that time by all mankind. The disease was enervated and its malignity spent; and let it proceed from whencesoever it will, let the philosophers search for reasons in nature to account for it by, and labor as much as they will to lessen the debt they owe to their Maker, those physicians who had the least share of religion in them were obliged to acknowledge that it was all supernatural, that it was extraordinary, and that no account could be given of it.

If I should say that this is a visible summons to us all to thankfulness, especially we that were under the terror of its increase, perhaps it may be thought by some, after the sense of the thing was over, an officious canting of religious things, preaching a sermon instead of writing a history, making myself a teacher instead of giving my observations of things; and this restrains me very much from going on here as I might otherwise do. But if ten lepers were healed, and but one returned to give thanks, I desire to be as that one, and to be thankful for myself….

It was a common thing to meet people in the street that were strangers, and that we knew nothing at all of, expressing their surprise. Going one day through Aldgate, and a pretty many people being passing and repassing, there comes a man out of the end of the Minories, and looking a little up the street and down, he throws his hands abroad, “Lord, what an alteration is here! Why, last week I came along here, and hardly anybody was to be seen.” Another man—I heard him—adds to his words, “’Tis all wonderful; ’tis all a dream.” “Blessed be God,” says a third man, “and let us give thanks to Him, for ’tis all His own doing, human help and human skill was at an end.” These were all strangers to one another. But such salutations as these were frequent in the street every day; and in spite of a loose behavior, the very common people went along the streets giving God thanks for their deliverance.

It was now, as I said before, the people had cast off all apprehensions, and that too fast; indeed we were no more afraid now to pass by a man with a white cap upon his head, or with a cloth wrapped round his neck, or with his leg limping, occasioned by the sores in his groin, all which were frightful to the last degree, but the week before. But now the street was full of them, and these poor recovering creatures—give them their due—appeared very sensible of their unexpected deliverance; and I should wrong them very much if I should not acknowledge that I believe many of them were really thankful. But I must own that, for the generality of the people, it might too justly be said of them as was said of the children of Israel after their being delivered from the host of Pharaoh, when they passed the Red Sea, and looked back and saw the Egyptians overwhelmed in the water: viz., that they sang His praise, but they soon forgot His works.

I can go no farther here. I should be counted censorious, and perhaps unjust, if I should enter into the unpleasing work of reflecting, whatever cause there was for it, upon the unthankfulness and return of all manner of wickedness among us, which I was so much an eye-witness of myself. I shall conclude the account of this calamitous year therefore with a coarse but sincere stanza of my own, which I placed at the end of my ordinary memorandums the same year they were written:

A dreadful plague in London was

In the year sixty-five,

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away; yet I alive!

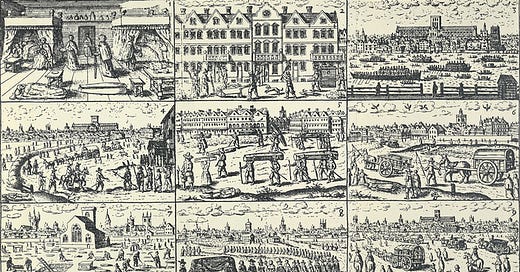

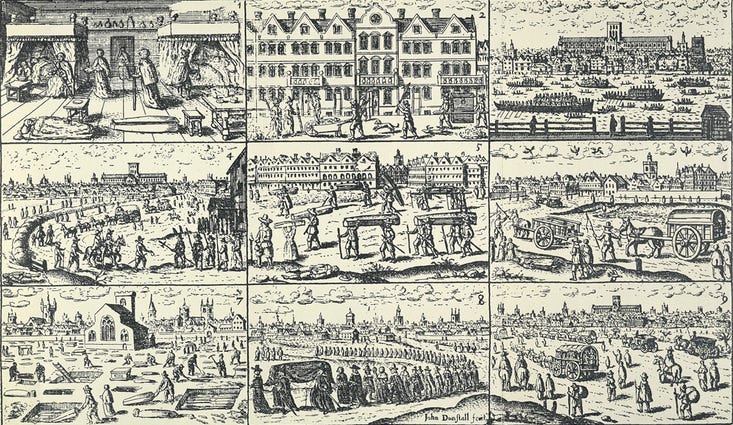

Photo credit: Drawings by John Dunstall of the Great Plague of London and its aftermath, 1666.

Love this piece.

Congratulations to your parents on their 51st Wedding Anniversary.

I appreciate you sometimes weave poetry in your writing, it makes your piece all the more fascinating and interesting, to me.

This is just so interesting. So well written and insightful. The story of your parents and their picture is wonderful and sweet. No freaking pandemic can take away their 50th anniversary.