Dear Reader,

Last Saturday, for the seventeenth or eighteenth time since we moved upstate, I went to the book fair at Elting Library in New Paltz. Under big tents in the parking lot, on long tables fifty feet deep, were rows and rows of books, all priced to sell: paperbacks a dollar, two bucks for hardcovers, a bit extra for something old or oversized. For a bibliophile like me, this is Christmas.

When I hit the book fair, I’m not there to socialize. I’m Seal Team Six, I’m on a mission. In years past I’ve brought a wheeled suitcase with me, but this time I made do with some recycled shopping bags. Like Willie Sutton, I slid my mask over my nose and mouth, pulled my hat down over my eyes, and went to town.

A few weeks before the fair, I’d myself donated two boxes of books, some of which I spotted as I worked the tables. I also came across a copy of Dirty Rubles—but, happily, no Fathermucker or Totally Killer. (You can’t help but feel the jarring pang of rejection, finding your own book at a book fair: someone didn’t want to keep this.)

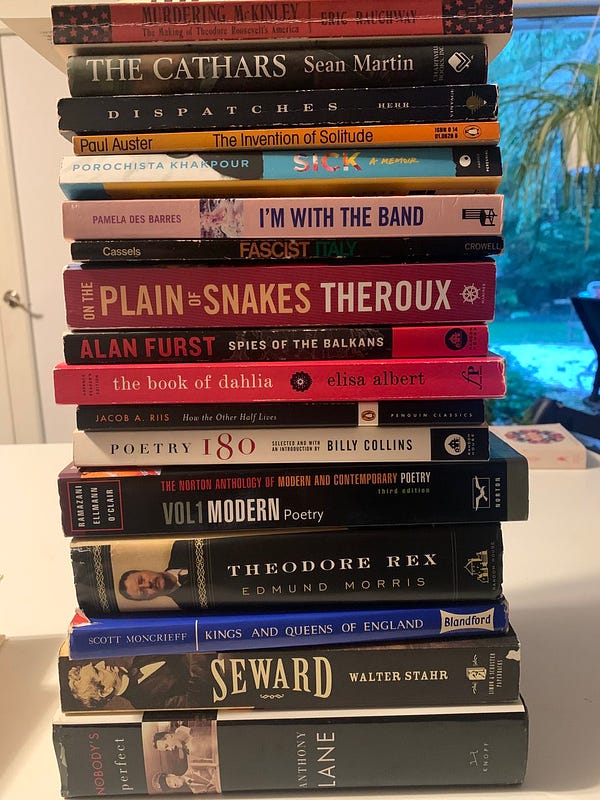

Between my wife, my son (the one who doesn’t subscribe to the Larkinian “get stewed, books are a load of crap” philosophy), and I, we filled three bags with books, and the total was less than sixty bucks—all the proceedings funding our lovely library. It was a good haul this year. There were titles I was legit excited about, which isn’t always the case.

Yesterday, I finished reading the first of the book fair acquisitions: Murdering McKinley: The Making of Theodore Roosevelt’s America, by the historian Eric Rauchway. The blurb on the back cover calls the book “[a] compact masterpiece that explains more about the late nineteenth century than most historians know and yet is readable enough to take on an airplane,” which was high enough praise in 2003, when Murdering McKinley came out, but looks even more impressive today, because the blurber is none other than Substack legend Heather Cox Richardson—arguably the country’s most famous historian. As usual, HCR is right. It really is a compact masterpiece: beautifully written, it reads like a novel. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Who was the youngest U.S. president? Even my son (the Larkinian one, who doesn’t read books but somehow knows more presidential trivia than most adults) guessed JFK and was wrong. It doesn’t seem possible that the answer is one of the four venerable men carved in rock on Mount Rushmore, but it’s true: Theodore Roosevelt was just 42 when he assumed the presidency upon the death of William McKinley, a week after the latter was shot by an assassin in Buffalo.

McKinley was, it seems to me, the first of the modern-day Republicans. A stodgy figure, religious, not corrupt but not terribly concerned with the plight of the downtrodden, he was all about helping corporations, serving his wealthy benefactors (like Marco Rubio, he himself was not rich, and in fact had been badly in debt), and indulging in American imperialism. It was during McKinley’s term that the U.S. acquired Puerto Rico and the Philippines. He was the sort of guy Dr. Seuss would make fun of: Business is business, and business must grow.

TR, by contrast, was a get-shit-done type: loud, adventurous, bombastic, empathic, and happy to be in the spotlight. As Rauchway says, he was “a Manhattanite who could credibly wear a cowboy hat.” How many humans have ever managed that trick? With the MAGA obsession with “alpha males,” Teddy Roosevelt would have turned the likes of Nick Adams into a pool of jelly. Which is why the party insiders made him VP: to brick him up in the dungeon of the vice presidency, where he could do no damage to the moneyed interests of the 1900 Republican Party.

John Wilkes Booth is rightfully infamous, having caused so much woe by killing Lincoln and elevating the Confederate sympathizer Andrew Johnson to the presidency, and everyone knows that little shit Lee Harvey Oswald. But if you can name McKinley’s killer, Dear Reader, you get a gold star. And yet the removal of the 25th president—and the ascension of the young and dashing Theodore Roosevelt to the White House—at that precise moment in time jump-started the progressive movement. TR was not as liberal as Jacob Riis, Jane Addams, or Booker T. Washington—his friends and allies—nor was he a radical like Emma Goldman and her crew. But compared to McKinley, he was a veritable revolutionary. It was like replacing your speed-limit-abiding grandmother at the wheel of the Skylark with Mario Andretti. Put it this way: Teddy’s fourth-cousin-once-removed was not the only Roosevelt who brought about massive positive change for the working people of the country. And without McKinley’s extremely timely death, none of that happens.

Rauchway writes:

Traditionally, historians see McKinley’s death as finally making way for political modernization, a terrible but effective way of clearing the decks. Students of American history take guilty pleasure in McKinley’s end: at the dawn of the twentieth century in the United States, all forces sloshed aimlessly at a grim doldrums. The Spanish-American War was the only excitement in a presidential Administration dourly concentrated upon that perennial bore of old American politics, the tariff. At the center of this dull debate over exclusion and reciprocity was the substantial, respectable figure of the godly McKinley, who could not be bothered to leave his front porch to run for president against William Jennings Bryan. Suddenly a wild-eyed anarchist bearing an unpronounceable name chockablock with consonants looms out of a crowd and strikes McKinley down. Theodore Roosevelt takes the helm and off shoots the ship of state in five directions at once, leaving the nineteenth century far astern, and it is not till 1921 that Harding Republicans can begin to restore normalcy (and, not incidentally, the importance of the tariff with it.) In a sense, therefore, William McKinley had two killers: the man who shot him and destroyed his body, and the the man who succeeded him and erased his legacy. This book tells the story of how both earned their historical roles—anarchist assassin, progressive President—through an act people preferred to regard as mad.

Czolgosz. That was his name: Leon Czolgosz. A native-born American of Polish descent, and not the immigrant the press demonized in the wake of the assassination. A self-styled anarchist, but one snubbed by the actual anarchists. (Emma Goldman’s initial assessment of the crime was that he should have taken out a wealthy captain of industry and not some broke-ass politician—the 1901 Musk, not the 1901 Trump.) A bookish loner too bashful to talk to women, and not the lothario of subsequent legend.

Rauchway’s book is, among other things, a character study of the two main players, Roosevelt and Czolgosz. It highlights the weird irony of how the new president roundly condemned anarchists and assassins and then helped implement progressive legislation that was exactly the sort of thing Czolgosz and the anarchists sought. And it’s impossible to read about Addams and Riis and Washington and even Goldman and not walk away both impressed by their achievements and grateful that they existed.

We are in a similar period now. Corporations have too much control. The Court is an impediment to progressive change. The gap between haves and have-nots is too wide and widening. Plutocrats want to do away with organized labor. The priorities of the political parties, their membership and their reach, are in flux. Thanks to Trump, tariffs are once again a topic of discussion. Too, a strange confluence of events—not an assassination but a miserable plague and a criminal in the Oval Office—brought an unexpected president to the White House. Theodore Roosevelt was the youngest president when his term of office began; Joe Biden was the oldest—at 78, almost twice TR’s age. And yet both were, improbably, the right men for the moment.

Roosevelt was shot, too. In Milwaukee, in 1912. After four years in hibernation, he was running again for president, as a third-party progressive. His campaign was foundering. He was on the way to an important campaign event, and despite having just been shot, he gave the speech anyway. (This would have broken Twitter if it happened today.) In that speech, he defined the progressive agenda as “a movement for justice now—a movement in which we ask all just men of generous hearts to join with the men who feel in their souls that lift upward which bids them refuse to be satisfied themselves while their countrymen and countrywomen”—yes, he really used the inclusive language—“suffer from avoidable misery.”

It sounds like something Biden would say—and, more importantly, mean.

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 this Friday was Gen Z activist and iGen podcast cohost Victor Shi:

Photo credit: Leon Czolgosz, 1900.

“a Manhattanite who could credibly wear a cowboy hat.”

Reminds me of my favorite line from Blazing Saddles. "What's a dazzling urbanite like you doing in a rustic setting like this?"

The longer I follow you the more I learn! Thanks Greg, interesting as as usual! My MIL always went to our library’s book fair!!