Dear Reader,

On May 10, 1931, the 36-year-old American “poetpainter” Edward Estlin Cummings boarded a train in Paris bound for Moscow. His two-month tour of Stalin’s dominions was chronicled in EIMI: A Journey Through Soviet Russia, a short book published two years later, which reads like a tourist diary filtered through the Molly Bloom section of Ulysses.

At the time, nine years after the Bolsheviks took over the country, there was considerable enthusiasm in American artistic circles for the new Russian government, which was touted by many well-meaning progressives as a cooperative utopia, if not “the future of mankind.” Cummings was, as Madison Smartt Bell puts it is his Preface to the 2007 edition, “[i]ndividualistic to a point near anarchy,” and “presciently suspicious of the Soviet regime, whose insistence on collectivism struck him as repressive, even by report. But he wanted to see for himself.” Spoiler alert: he did not like it.

Here is Cummings’ account of entering Russia proper and changing trains to proceed to Moscow:

In a world of Was—everything shoddy; everywhere dirt and cracked fingernails—guarded by 1 helplessly handsome implausibly immaculate soldier. Look! A rickety train, centuries BC. Tiny rednosed genial antique wasman, swallowed by outfit of patches, nods almost merrily as I climb cautiously aboard. My suitcase knapsack typewriter gradually are heaved (each by each) into a lofty alcove; leaving this massive barrenness of compartment much more than merely empty (a kissing sickle and hammer sink in heaver’s palm, almost child trickles away). Dizzily myself seeks Fresh Air.

Soviet Russia, for him, was an “uncircus of noncreatures.” Later, Cummings described it as a “subhuman communist superstate, where men are shadows & women are nonmen; the preindividual marxist unworld,” where unworld is both a truncation of underworld and the opposite, or the absence, of world.

And in case we missed the point, he adds: “This unworld is Hell.”

So, yeah: not a fan.

I did not know any of this until yesterday. I only knew Cummings through his poems—distinctive, eccentric, witty, funny, at times erotic, at times bordering on sentimental, and always thumbing a nose at convention, at the prevailing sentiments of what he derisively called “mostpeople.” I didn’t know about his paintings, which he held in the same regard as his poetry. I didn’t know about the plays or the prose work. I didn’t know anything about his background, or realize he lived for most of his life in a little cul-de-sac off Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village—a few blocks from The Strand, and a short walk from where I lived my one semester at NYU. I didn’t even know what he looked like (short, thin, with thinning hair and big ears and penetrating eyes close together, his face knotted in judgment, as if daring you to put one past him).

Any writer of the Lost Generation exhibited a healthy amount of cynicism. They were born into an era where there were basically no civil rights for women, people of color, LGB people, unionists, factory workers, and so on. They grew up in the rough and tumble Progressive period; came of age during the Great War, when the nations of Europe destroyed each other to satisfy the whims of their insecure kings; came home to a nation where the bars were all closed; and as soon as they got on their feet, watched the stock market crash and the country slide into an economic depression that lasted for a decade and a half. Not fun.

But even in that jaded peer group, Cummings stands alone. Perhaps because of his experiences during the war, when he volunteered for the ambulance corps and wound up being held for months on suspicion of treason for daring to befriend the soldiers, he trusted nothing, regarded everything with suspicion: fascism, socialism, artistic movements, literary criticism, punctuation. He was, in a word, intimidating. He’s not a historical figure I’d like to have had dinner with; I get the sense that he would have taken one look at me, with that hard, judgmental glower of his, and seen right through all pretense—just as he saw through Stalin’s smoke and mirrors, just as he recognized Walter Duranty, the New York Times reporter who filed glowing reports about the Soviet Union, as a slinger of bullshit.

He was that rarest of rare literary creatures: a writer who didn’t give a fuck what anyone else thought of him. This often worked to his detriment. After the release of EIMI, Cummings had trouble getting published, as most editors, who leaned Marxist, regarded him as a reactionary nutjob for not drinking the Stalinist Kool-Aid.

Generally, I don’t much care for the “modernist” style, with its word salad and contempt for noun-verb agreement and chronic abuse of parentheses and commas. Gertrude Stein wrote like that, and Ezra Pound, and John Dos Passos. To me, it feels like, at best, a writing experiment gone awry, and at worst, a literary fad. The only enduring line of the three writers just named, at least for me, is Stein’s memorable phrase, “Rose is a rose is a rose,” which, I mean, sure. James Joyce dabbled in this form, notably in certain sections of Ulysses and most of Finnegan’s Wake; I would argue that his work would have been even stronger, and certainly more accessible, had he simply stuck with what my English professor called “lucid Joyce”—and based on the response to Joyce in the creative writing class I taught ten years ago and in the comments section here at “Sunday Pages,” I am not alone in this opinion.

Cummings, and Cummings alone, makes that modernist style sing. I don’t always understand why he, for example, puts a comma where one should not be and omits a comma where one should, or why he doesn’t close parentheses, or why he breaks a line in the middle of a word or leaves no space before a comma, or what his beef is with hyphens. But the point of the poems always shines through, and unlike with Pound or non-lucid Joyce, the style enhances what he has to say. The humor is evident, and the wit, and the passion. Is this because he’s usually writing about simple subjects, like love and flowers? Is it because he doesn’t take himself too seriously?

In one of his six “nonlectures” on poetry given at Harvard, his alma mater, in 1952-53, Cummings dances around such pretentions. “Why in the name of common sense doesn’t the poet (socalled) read us some poetry—any poetry; even his own—and tell us what he thinks or doesn’t think of it?” he imagines one of the attending students wondering. “Is the socalled poet a victim of galloping egocentricity or is he just plain simpleminded?”

(The use of galloping there is gaspingly good.) And then he answers said imaginary student:

My immediate response to such a question would be: and why not both? But supposing we partially bury the hatchet and settle for egocentricity—who, if I may be so inconsiderate as to ask, isn’t egocentric? Half a century of time and several continents of space, in addition to a healthily developed curiosity, haven’t yet enabled me to locate a single peripherally situated ego.

I read that excerpt yesterday and literally LOL’d. I mean, peripherally situated? Amazing. I can’t imagine Pound, for example—now forgotten but a literary titan in his day—coming up with something so self-deprecating or so funny.

But we wouldn’t be expounding on E.E. Cummings here if not for the poems. The style is immediately recognizable, the voice is pure, and while he plays around with grammar and punctuation etcetera, there is no missing the point.

“my sweet old etcetera” is one of my wife’s all-time favorites. “It’s the first poem that made me cry,” she told me. Cummings wrote this masterpiece in 1926:

my sweet old etcetera

aunt lucy during the recentwar could and what

is more did tell you just

what everybody was fightingfor,

my sisterisabel created hundreds

(and

hundreds)of socks not to

mentions shirts fleaproof earwarmersetcetera wristers etcetera,my

mother hoped that

i would die etcetera

bravely of course my father used

to become hoarse talking about how it was

a privilege and if only he

could meanwhile myself etcetera lay quietly

in the deep mud etcetera

(dreaming,

et

cetera,of

Your smile

eyes knees and of your Etcetera)

Et cetera is Latin for “and other things.” It’s almost always written as “etc.” and sometimes “&tc.” Cummings spells out the full word all eight times he uses it in the poem. Each time it means something slightly different. The penultimate and antepenultimate times, he breaks the line between et and cetera, forcing us to take a little more time to process the words, as our narrator lies in the mud daydreaming. And the last time, significantly, is the only instance where the word is capitalized.

There are no atheists in the foxhole, the saying goes. But here our narrator, deep in what we presume are the trenches, prays to a different sort of god. All of the bullshit melts away—the reasons for the war; the valor—and all that’s left is a lusty young man who knows what’s really important. Note that there is no heroism at work here, no pretense of “I’m fighting the bad guys to save you, my darling.” He’s literally lying down in the mud, passive as passive can be. Therein lies the sweetness, for the poem is sweet, as the first line/title suggests.

Probably because of his firsthand experiences in Soviet Russia, Cummings, like Dos Passos and Pound, became more conservative as he got older. Pound, of course, wound up a legit and active fascist. Cummings would never go that far—although he was, as Ross Wetzsteon explains in Republic of Dreams: Greenwich Village, “as much a New England Yankee as Calvin Coolidge, a devout Republican, and a bit of an anti-Semite. In his later years”—he died in 1962—“he was a fierce defender of Joseph McCarthy and a curmudgeon who felt that the beatniks were further desecrating an already despicable American culture with their sloppy writing and even sloppier appearance.” (He wasn’t exactly wrong about the beatniks, it says here.)

What would he have made, one wonders, of MAGA and of Trump? While I could easily see Pound occupying a Kevin Sorbo space in today’s social media—“The best writer they could find is Ezra Pound? Ha!”—I can’t imagine Cummings, with that keen nose for bullshit, warming to Donald Trump. He didn’t like frauds, he didn’t like performative gestures, he didn’t like meanness, he didn’t like mass political movements or cult-like behavior. Above all, he didn’t like artlessness. And artlessness, as my friend LB has pointed out many times, is the hallmark of MAGA.

The last lines of “proud of his scientific attitude,” a Cummings poem about an artless fraud, feel extra relevant to the here and now: “hear / ye!the godless are the dull and the dull are the damned.”

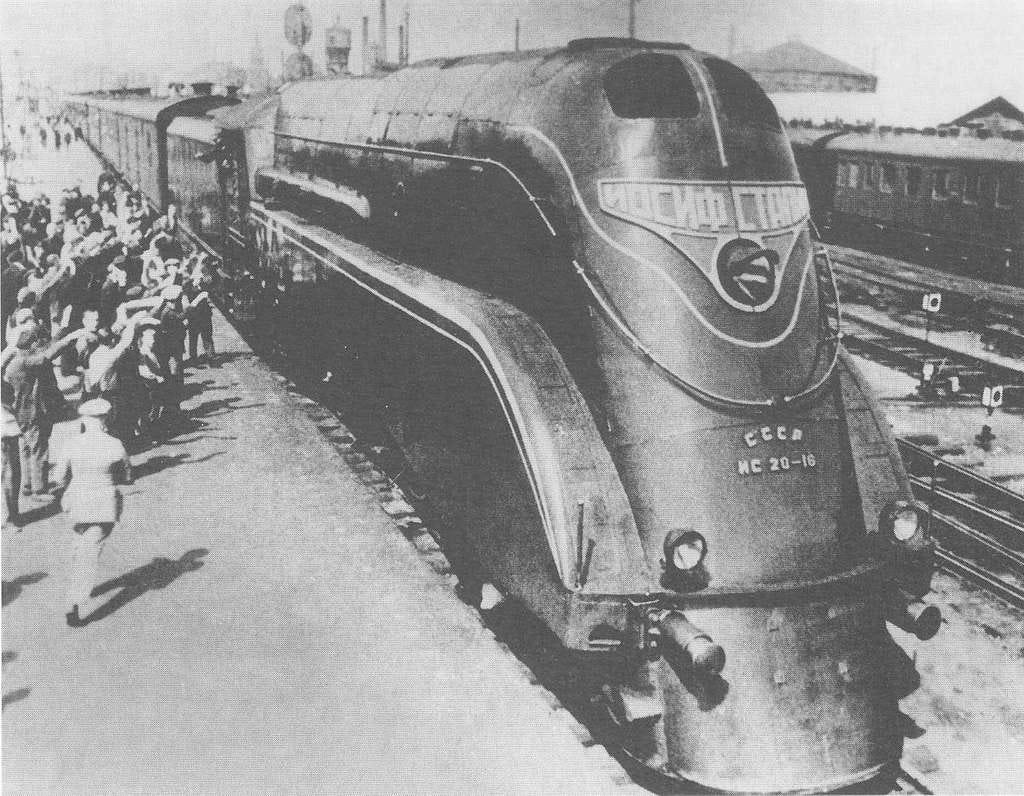

Photo credit: Russian steam train, 1937.

My goodness, Greg. What a lesson for an English major this morning. Thank you for bringing the past to the present so poetically.

Wonderful snapshots and ponderings. You put the sun in Sunday morning.

The grammar and punctuation things always sort of irk me, but it's priceless how the poem manages to be such deceptively unassuming hilarious tearjerkery.

He definitely would not have discovered "peripherally situated ego" at Trump's address.