Dear Reader,

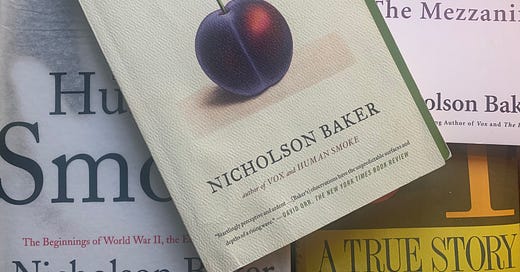

Nicholson Baker is one of my favorite writers. For one thing, I am in awe of his talent, the breadth and depth of his creative power. The guy can do anything. His first novel, 1990’s The Mezzanine, is a slender but book-length record of the rambling thoughts of an office worker on his lunch break; there is a meditation in that book, I believe in one of its many page-long footnotes, that goes into great detail about the drinking straw, and, for real, it’s absolutely riveting.

For another, I admire that he writes about whatever the hell he wants, without regard to how a work might affect his reputation. When House of Holes—a sort of Hieronymus Bosch of a novel, subtitled, with good reason, A Book of Raunch—came out in 2011, the New York Times wrote a profile of him under the headline “The Mad Scientist of Smut.” “Nicholson Baker does not look like a dirty-book writer,” the piece begins. “His color is good. His gaze is direct, with none of the sidelong furtiveness of the compulsive masturbator.” I can’t imagine another writer of Baker’s stature that the paper of record would write something like that about.

House of Holes is his third “dirty” book. The first, The Fermata, concerns the exploits of a guy who can stop time, and uses that X-Men-like superpower to undress women. Vox, the second, presents as a transcript of a man and a woman talking on a pay-to-play phone-sex line. I don’t really love his erotic books—while I do recall having a stray, prurient thought in maybe third grade about what mischief I’ve get into if I had the ability to stop time, there is very little overlap in the sexual fantasy Venn diagram of Nicholson Baker and Yours Truly—but I love that he writes them, and puts as much creative effort and energy into them as anything else, and publishes them under his own name. (Who does love his erotic books, famously, is Monica Lewinsky, who gave a copy of Vox to Bill Clinton.)

U & I is a sort of literary examination of the work of John Updike, but not in the obvious sort of way. Baker doesn’t read more Updike than what he’d already read when he began the project, uses quotes from memory that are often not exactly correct, and talks a great deal about how he, as a reader and then a writer, learned from Updike, was shaped by Updike, could only tremble at the godlike presence of Updike, like a human cowering before General Zod. It contains this excerpt, an enviably gorgeous piece of writing, that involves Baker’s concerns about the Updike project he is working on:

In theory I resist the campy adult celebration of Halloween; and in theory I reject [pretentious literary critic] Harold Bloom’s allegories of literary influence and parricide and one-upmanship (of which more later, I hope); but when I heard that the editor of The Atlantic had said that what I was doing sounded “creepy,” and when I thought again of another of Updike’s phrases from Self-Consciousness that somebody quoted in a review, “Celebrity is a mask that eats into the face,” I realized that like it or not I was clearly risking with this essay the charge that I was simply engaged in a little trick-or-treating of my own on Updike’s big white front porch.

Apart from the early short story about the kid quitting his job at the A&P, I always found Updike overrated—more significant as a cultural figure of that particular moment in time than anything else. I never really got him. He wasn’t writing for my generation. Nevertheless, Baker makes the whole book sing.

In addition to all this disparate stuff, Baker wrote Human Smoke, which was, for me, extremely influential in terms of the subject (it is an examination of pacifism, through the lens of the Second World War) and the technique (short paragraphs that set up and quote primary sources, with no editorializing at all). To anyone interested in a review of the lead-up to the war from a perspective not much covered in the press or the popular culture, it is a must-read. Human Smoke came after his 2004 antiwar novel Checkpoint, presented as a discussion between two men: one who wants to assassinate George W. Bush and one who tries to talk him out of it.

But for today’s “Sunday Pages,” I wanted to share some excerpts from my favorite of Baker’s books: The Anthologist. This is a (for him) conventionally structured novel about a poet, Paul Chowder, who is in the process of the selecting poems for, and writing the introduction to, an anthology he’s been asked to put together. His life is falling apart around him, he has writer’s block, and he can’t get his shit together to do the job properly. Most of the novel takes place in his head. But the whole book is a sort of love song to poetry. It’s a “Sunday Pages” kind of novel.

In this excerpt, you get a good taste of Baker—modest about himself, smart, astonishingly perceptive, funny, writing in a prose style that is deceptively simple:

There’s no either-or division with poems. What’s made up and what’s not made up? What’s the varnished truth, what’s the unvarnished truth? We don’t care. With prose you first want to know: Is it fiction, is it nonfiction? Everything follows from that. The books go in different places in the bookstore. But we don’t do that with poems, or with song lyrics. Books of poems go straight to the poetry section. There’s no nonfictional poetry and fictional poetry. The categories don’t exist. . .

Coleridge says that Alph the sacred river ran through caverns measureless to man. Did it really do that? John Fogerty says that the old man is down the road. Is he? Longfellow says he shot an arrow into the air. Did he, or is he just saying he did? Poe said there was a raven tapping at his chamber door. Was there?

We don’t care. Why don’t we care? I don’t know. I don’t have an answer for you today on that important question.

And then he gets to the heart of the matter: the relationship between poems and tears. Why do beautiful poems make me cry? It’s not sadness; not quite. There’s something about the universal beauty of the art form, the rare ability of the poet to distill so much to so little. But the poet, Baker/Chowder argues, feels all the pain. To be able to chose the poems for an anthology, he writes, “you have to be willing to be sad.” And that sadness might lead you to think, wrongly, that you are depressed in the way poets tend to be:

And as a result, you may be tempted to think: I’m one of them. I’m John Keats. I’m Sara Teasdale. Or Longfellow. Or Louise Bogan. Or Ted Roethke—rhymes with “set key.” Or Alfred Lord Tennyson. Or John Berryman. Berryman, who wrote funny poems and then stopped writing funny poems and launched himself off a bridge and, flump, that was it for him. Many suicides. Percy Shelley. Many suicides.

So you might think to yourself, Oh boy, I am one of these great depressive figures. But you’re not. . . Not the way a real poet is depressed. You don’t even come close.

True poet’s depression is a rigor mortis of agony. It’s a full-body inability to function. You don’t want to leave your room. Louise Bogan summed in up in two quick lines. This was back in I don’t know when—nineteen-thirty-something. It was a poem in the New Yorker called “Solitary Observation Brought Back from a Sojourn in Hell.” And the lines went: “At midnight tears / Run in your ears.” She’s lying there on her back, crying. Her eyes are overflowing, and the tears are cresting and coming around, and down, and they’re flowing into her ears. There’s something direct and physical and interesting about that. Because it’s as if the crying leads directing to the hearing. Her grief leads to something audible—a poem. That’s what it does for all these really good poets. The crying and the singing are connected.

In the last seven years, as the Trump Era has unfolded, I have read more and more poetry and less and less anything else. Part of that is due to my attention-span problems, for sure. But there’s more to it than that. Poetry is uniquely able to capture the bleakness of these times—and, by doing so, replenish my dried-up reservoir of hope.

“Poetry,” Baker writes, “is a controlled refinement of sobbing.”

ICYMI

Ukraine expert Victor Rud was our guest on The Five 8.

Please direct me to the place where I can "replenish my dried-up reservoir of hope."

What you said about Baker’s writing in the first two sentences of this piece is what I’d say about your writing and why I love Prevail. But I’ve told you that in previous comments. What needs to be added here is that your writing about other great writers is filling a previously unfulfilled need in me for literary guidance. My wife fondly recalls a high school teacher who strode into the classroom quoting Shakespeare. Others recall that one outstanding teacher who inspired them. I never had a really great teacher! If I’d had someone in my life back then who got excited about great writing like you do, I’d probably have read Tom Sawyer rather than using my cleverness to get ‘A’s in Literature by psyching out the multiple choice test questions. I’m a published author and professional technical writer who’s functionally illiterate in great literature. I’m making a promise to myself here and now based on the inspiration I’m getting from you: I promise to find time—perhaps by commenting less on Facebook—to start reading some of the great writing I’ve missed. It’s all your fault, Greg Olear! You done went and inspired me!