Dear Reader,

In Friday’s piece, I compared Trump’s infantile garbage truck performance to something out of Polish absurdist theatre. His Halloween turn as a big orange trash collector-cum-Fleshlight seemed like an act, a send-up, different than his usual insult-comic routine—although that too entered a whole new level of crazy at a rally on Friday night, as Donald pantomimed, rather convincingly, a vigorous act of fellatio, putting his puckered mouth and short fingers to good use.

But enough about that garbage human, who has already consumed too much of our collective creative energy; his hour of strutting and fretting on the stage will be over soon enough. The reason I mention this is because my allusion to Polish absurdist theatre made me realize that, while I’d learned about the existence of Polish absurdist theatre in college, I had never seen or read, and could not even name, a single Polish absurdist play or Polish absurdist playwright. That was fine, as far as Friday’s piece was concerned, but I was curious: What is Polish absurdist theater? Is it as silly as it sounds? Who pioneered it?

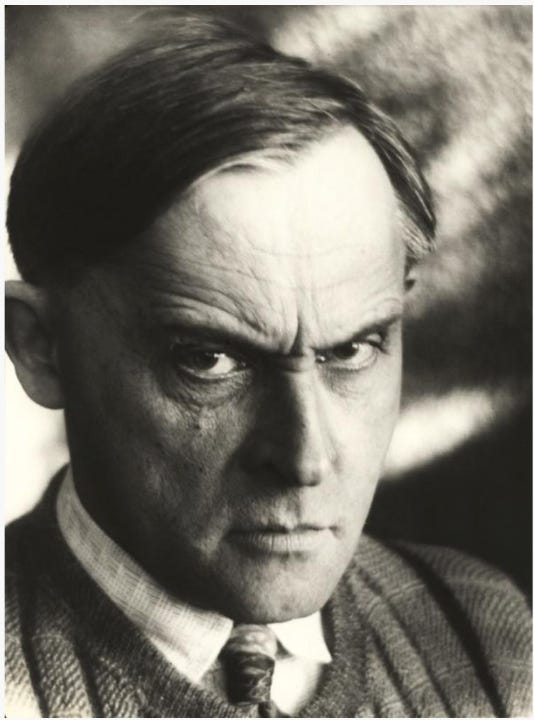

The answer to that last question is Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, who used the Banksy-esque nom de plume Witkacy, a sort of mashing together of his middle and last names. I decided to do a deep dive on this great Polish artist, and was both shocked and delighted to discover that he was, without qualification, a genius of the highest order. I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed exploring his prodigious output—and how badly my soul needed the pleasure that exploration gave me.

Witkacy wrote dozens of plays and at least one short film, in which he appears. He wrote novels. He wrote works of philosophy and musings about art and journals on his experiments with various drugs. He was a painter who painted in a number of distinct styles, each one better than the last. Like his contemporary Man Ray, he moved from painting to photography, producing a mesmerizing series of wonderful photographs. Mostly he was interested in people as subjects. Later in life, to earn more money, he ran a portrait studio, where he cranked out wonderful renderings of whoever chanced to come by—like one of those caricature artists you see on the boardwalk, but not caricature, and on a grander scale. These portraits, too, are astonishingly good.

Billy Gibbons, the guitarist from ZZ Top, said that if Prince had just played lead guitar—just that and nothing else—he still would have been iconic, because he did that better than most of the musicians who did just that professionally. (My brother, who is a virtuoso guitarist in the Randy Rhoads style, agrees.) He was so good, Gibbons said, that to properly convey the depth of his talent required “other superlatives. Because it’s almost got to the point of defying description.” Witkacy was like that. He worked in different forms of art, different styles, different modes—and he was sensational at all of them. He veritably radiated talent.

For starters, here is a clip that runs through 72 of his paintings—enough to fill a wing of a museum. It’s fascinating to see how he develops artistic ideas, plays around with colors and shading, experiments with style and composition. Even with the great artists, there are often paintings I don’t much care for. With Witkacy, I love all of it:

Born in Warsaw in 1885, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz was raised in the Polish resort town of Zakopane, at the foot of the Tatras Mountains. His father, also named Stanisław Witkiewicz, was a painter and art critic who had invented the “Zakopane Style.” The son, called Staś, was something of an artistic prodigy. Recognizing this inchoate talent, the elder Witkiewicz, who was something of a control freak, refused to send his son to public school and handled his instructions personally—the turn-of-the-century Polish version of homeschooling.

The family was plugged into the Polish artistic community. Staś was childhood friends, and probably more, with the painter Zofia Romer. His godmother was the renowned Shakespearean actress Helena Modjeska, the Meryl Streep of fin de siècle Poland. In a related story, he had a thing for talented actresses. He had an affair with the actress Irena Solska, a founder of the Young Poland artistic theatre movement, who was eight years older. That volatile relationship was the inspiration for his first novel, published when he was 26—the wonderfully titled The 622 Downfalls of Bungo, or, The Demonic Woman.

That Satanic modifier is not pejorative; to Witkacy, all art was demonic, and a demonic woman was therefore a sort of muse: Kali meets Erato. At least, that is the impression I got from one of his plays, “The Beelzebub Sonata,” which is less a piece of theatre than an excuse for characters on stage to pontificate about capital-A Art.

In this scene from Act Two, young Istvan, a musical prodigy, heads to the mouth of an old mine on the outskirts of the Hungarian town of Mordovar, and discovers that his companion, the distinguished gentleman Baleastadar, is, in fact, the Devil Himself:

BALEASTADAR: {Glaring at ISTVAN with a devastating look)

I am not Sir, I am Beelzebub, Prince of Darkness. Address me as: Your Highness. Understand, you might-have-been?ISTVAN: {Falling to his knees)

It’s frightening here. . . I don’t want anything . . . Just to get out of here . . .BALEASTADAR: {In a terrifying voice)

In you, I mortalize original sin by the artistic creativity which I kindle in you. Through art alone humanity remembers that everything in Existence is self-contradictory. Without art there’d be no life for me any more nowadays. I have no work to do among cattle reduced to mechanized pulp. But as long as art exists, I exist, and by creating metaphysical evil I satiate myself with existence on this planet. On the moons of Jupiter they have their own Beelzebubs.ISTVAN:

Oh, God! Save me! Mercy, Your Highness!BALEASTADAR:

Don’t you dare mention that Name here. For me it’s only the symbol of Nothingness, my own Nothingness—but I want to live, and I’m going to live. Yet I must live through someone else. Artists, they’re the only material for me nowadays. To create by destroying! The last form of strength left capable of blowing things up, now that the various religions which once created the evil spirit’s ghost have died. I personify all that—do you understand? What have you got a brain for? Think, but don’t feel anything.ISTVAN: {Falling into a state of catalepsy)

Something monstrous is turning my blood to ice. I feel the evil fang of an amorphous ghost ploughing my brain into zigzags of an inexpressible, lightning thought.BALEASTADAR:

What do you see?ISTVAN:

I see Mordovar the way it used to be, as in a dream, heightened to the limits of inhuman, bestial beauty. Masks are falling from the trees, mountains and clouds. I see a merciless black sky and a small stray globe which you, the Prince of Darkness, envelop with your bat-like wings. And I am a worm, a little caterpillar, crawling along the leaves, irradiated by the sinister glow of suns bursting in the Milky Way.BALEASTADAR:

Come down lower, to the level of your own feelings. Dig deep into yourself one last time.ISTVAN:

My feelings are pills prepared by some hideous interplanetary pharmacist and hurled into nothingness to be devoured by frozen, starving space.BALEASTADAR:

Lower still . . .ISTVAN: {Suddenly waking up from his cataleptic state)

I want to go back to Mordovar, to my aunt! {With a final attempt at labored irony.) You’ve entered into the role of Beelzebub wonderfully well, but I’ve had enough of this comedy.(BALEASTADAR him one on the head with his fist. ISTVAN stays on his feet and falls into the previous state all over again.)

ISTVAN:

This is the end. The very core of my being has gone numb in an icy blast from the center of Non-Being.BALEASTADAR: Do you understand now?

For me, the answer to Beelzebub’s question is, “No.” While I found the play ponderous and kind of dull, I like this excerpt because it shows both Witkacy’s reverence for high art and also his playfulness; the throw-away line that the moons of Jupiter have their own Beelzebubs interjects levity into an otherwise overwrought scene. (Also, “My feelings are pills prepared by some hideous interplanetary pharmacist and hurled into nothingness to be devoured by frozen, starving space” would make a helluva senior yearbook quote.)

Between 1911’s The Demonic Woman and 1925’s “The Beelzebub Sonata,” Witkacy endured more than his share of suffering, both emotional and physical. After his affair with Irena Solska, he was engaged to the painter Jadwiga Janczewska. Both Jadwiga and Staś had a flair for the dramatic, and their relationship was tumultuous, tortured, fractious, and complicated by the fact that Janczewska was in love with their mutual friend Karol Szymanowski, a composer like Istvan, who, just to make things even more complicated, was gay. After one of their many quarrels, she marched off to the base of the mountains, wrote out a nonsensical suicide note, and, still holding a bouquet of flowers Witkacy had given her, shot herself through the temple with a Browning pistol.

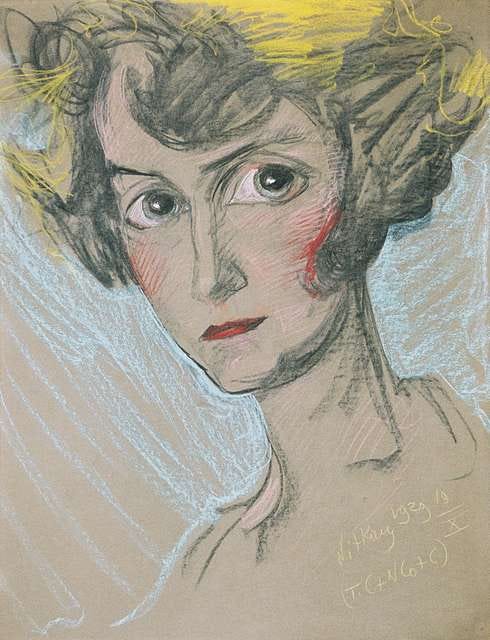

This is a photograph he took of her in happier times, which eerily foreshadows her fate:

Jadwiga died in February 1914. Six months later, after a detour to Papua New Guinea, Witkacy found himself a conscript in the Russian army. At the time, there was formally no Poland; he was technically a citizen of the Russian Empire, and believed it was his duty to enlist. This broke the heart of his father, a Polish patriot who loathed the Russians; the ender Witkiewicz died in 1915, estranged from his son.

Witkacy was severely wounded in combat in Ukraine. He was taken back to St. Petersburg to recover, and from his window at the hospital there, he literally witnessed the Russian Revolution. (From that vantage point, he was able to see through the Bolshevik bullshit, and was not a fan.)

Staś took his art seriously—to Witkacy, art was more important than anything—but he was also funny and silly and ironic and aware of the futility of it all. He was simultaneously avant garde and contemptuous of modern life, radical and conservative. In New Forms in Painting and the Misunderstandings Arising Therefrom, written while convalescing at the hospital, he wrote:

Each epoch has the kind of philosophy that it deserves. In our present phase, we do not deserve anything better than a narcotic of the most inferior sort which has as its goal the lulling to sleep of our antisocial metaphysical anxiety which hinders the process of automatization. We have this narcotic in excess in all forms of philosophical literature throughout the entire world. . .

The loneliness of the individual in the infinity of Existence became unbearable for man in the as-yet-incompletely-perfected conditions of societal life, and therefore he set out to create a new Fetish in place of the Great Mystery—the Fetish of Society, by means of which he attempted to deny the most important law of Existence: the limitation and uniqueness of each Individual Being—so that he would not be alone among the menacing forces of nature. . .

Metaphysical truths are pitiless, and it is not possible to make compromises about them without producing inconsistencies. Given the way the problem is posed now, the only way out is to forbid people to search for the truth as though that were a kind of fruitless unhealthy mania from which mankind has already suffered long enough throughout the centuries.

In short, Staś didn’t like where art and literature were headed. If he were suddenly reanimated in 2024, he would take one look at TikTok and conclude that he’d gone to Hell—actual Hell, not the kind of Hell where lived demonic women:

We do not maintain, however, that to be a genius one has to drink oneself to death, or be a morphine addict, a sexual degenerate, or a simple madman without the aid of any artificial stimulants. But it is a frightful fact that whatever great occurs in art in our agreeable epoch happens almost always on the very edge of madness. . . In our opinion, true artists—that is, those who would be absolutely incapable of living without creating, as opposed to other adventurers who make peace with themselves in a more compromising fashion—will [in the future] be kept in special institutions for the incurably sick and, as vestigial specimens of former humanity, be the subject of research by trained psychiatrists. Museums will be opened for the infrequent visitor, as well as specialists in the special branch of history: the history of art—specialists like those in Egyptology or Assyriology or other scholarly studies of extinct races: for the race of artists will die out, just as the ancient races have died out.

In “The Nitwit’s Smirk,” part of an eclectic collection of short pieces called Unwashed Souls, he expounds on this everything-has-gone-to-the-dogs idea—and may as well be writing about the artless MAGA of 2024:

My voice sounds as faint as a mosquito’s buzz in comparison to the banalizers’ megaphones, but the fact is that I issued warnings many times against various things: the excessive acceleration of life, the decline of theatre and literature (as a result of sucking up to a public which grows more moronic from one day to the next), anti-intellectualism, and the threat of total guanification of people’s brains.

I mean: banalizer! Guanification! That’s good stuff!

In 1925, he moved back to Zakopane and, sick of being broke, established The S.I. Witkiewicz Portrait Painting Company. Customers could go to the studio, fork over a few hundred złoty, and sit for a portrait. But there were strict rules that had to be observed. Witkacy was not one for taking shit from unlearned critics:

#3. Any sort of criticism on the part of the customer is absolutely ruled out. The customer may not like the portrait, but the firm cannot permit even the slightest comments without giving its special authorization. If the firm had allowed itself the luxury of listening to the customers’ opinions, it would have gone mad a long time ago. We place special emphasis on this section, since the most difficult thing is to restrain the customer from making remarks which are entirely uncalled for. The portrait is either accepted or rejected —yes or no, without any explanations whatsoever as to why. Inadmissible criticism likewise includes remarks about whether or not it is a good likeness, observations concerning the background, placing one’s hand over part of the face as painted in order to imply that this part really isn’t the way it should be, comments such as, “I am too pretty,” “Do I look that sad?” “That’s not me,” and all other opinions of that sort, whether favorable or unfavorable. After due consideration, and possibly consultation with third parties, the customer says yes (or no) and that’s all there is to it—then he goes (or does not go) up to what is called the “cashier’s window,” that is, he simply hands over the agreed-upon sum to the firm.

And why does he insist upon this very specific rule? “Given the incredible difficulty of the profession, the firm’s nerves must be spared.”

As if all of that weren’t enough, Witkacy also wrote a seminal work of speculative fiction called Insatiability—a complicated, dense tome in the manner of Pynchon or Joyce. It was published in 1930, two full years before Brave New World, and seems like a blend of Aldous Huxley, Philip K. Dick, and Henry Miller, with a pinch of Charlie Kaufman. Scott Spires has an excellent writeup about it at the Lakefront Review of Books:

Writing roughly a century ago, Witkiewicz…created a future world that eerily anticipates our own. “Witkacy had a seismograph in his head attuned to the tremors of history,” said the critic Jan Kott, and that seismograph is operating at full strength in Insatiability. Here we can find the rise of China; the use of drugs to promote psychological well-being; odd and extreme ideologies; and the growth of automation. All of this plays out in an exhausted Western world which has lost any belief in itself, and where the upper classes wallow in various forms of decadence.

The character who holds the whole messy thing together is one Genezip Kapen (also called Zipcio, Zipek, Zipon, Zippy, and even Zippiepoo). Insatiability is formally a Bildungsroman, following his transformation from privileged son of a brewing magnate to military aide to the commander of the Polish army, a strongman supposedly based on Poland’s interwar leader, Marshal Piłsudski. . . .

All of this takes place while a Chinese army is making its way toward Europe, bent on conquest. Early in the narrative, we find out that Moscow has fallen to the Chinese, so Poland is now the first (and possibly last) line of defense for Western civilization. However, much like Zipcio, the intellectual and aristocratic classes are succumbing to their own metaphysical and psychological preoccupations, and have become obsessed with other distractions. These include dissonant music, esoteric forms of philosophy, religious cults, and last but certainly not least, sex and drugs.

It is in this perfervid atmosphere that a new cult appears and begins to attract adherents in the West. Murti-Bing, a mysterious Mongolian philosopher and guru, has somehow devised a pill that induces in those who take it a sense of “self-annihilation and cancellation of the past.”

So: Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind!

I come back to Gibbons’s quote about Prince, which also applies to Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz. If we isolate just his early paintings, just his photography, just his portraits, just his plays—just Insatiability, for that matter; does anyone recall Huxley for anything other than Brave New World?—any one of those contributions would be enough to secure his legacy as an artistic genius. Witkacy did all of that.

What was he like in person? Wanda Jakubińska-Szacka, who starred in a production of one of his plays in Łódź, had this to say about him:

He was beautiful. Tall, well-built, with dark hair and a dark, seemingly brooding face, which got suddenly lit up with very light blue eyes. He had a poignant gaze, a steel one. He came to Łódź, because we were meant to perform his play “Persy Zwierżątkowskaja.” . . .And once again, a surprise. Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz was incredibly modest. He did not believe in success, nor was he convinced of the exceptional quality of his play.

He came to the last rehearsals. I suppose it is needless to add that the play was shocking for us every possible way. The content? Today I don’t attempt to describe it, I simply don’t remember. But I clearly remember the words with which Witkiewicz responded to our pressing questions: “There are three basic engines of all human activity: money, women, and power.” Each of the three acts corresponded with one of these affairs. But in the end, it was money that won.

To create portraits as skillfully as he did, Witkacy had to have possessed an exceptional ability to quickly size up the essence of his subjects. Remember again the critic’s quote about him: “Witkacy had a seismograph in his head attuned to the tremors of history.” He had seen firsthand what was afoot in Russia, with the hypocritical Bolsheviks, and he didn’t care for it. The Nazis, led by the failed watercolorist with the terrible mustache and the shitty artistic taste, were just as bad if not worse. As a painter still plugged into the Polish artistic community, Witkacy was surely aware of Hitler’s naked looting of Europe’s artwork. He had no illusions about what the rise of the Third Reich meant for Zakopane, for artists, and for Poland, just as he knew exactly what Stalin was.

The Nazi invasion of Poland began on September 1, 1939. Witkacy and his lover, Czesława Oknińska, fled to a small town in the eastern part of the country, in what is now part of western Ukraine. His goal, it seems, was to get as far away from the Germans as possible. When the Soviets invaded Poland sixteen days later, that seismograph in his head went haywire. The tremors became tectonic shocks. The future could be seen on a map: Nazi Germany to the left, Soviet Russia to the right—and there was poor, defenseless Poland, smack dab in the middle. He knew it was hopeless.

As a habitual user of all manner of drugs—alcohol and nicotine; morphine and other narcotics; even peyote—Witkacy knew what would constitute a fatal dose. On September 18, 1939, the day after the Soviet invasion of Poland, he consumed enough Luminal to kill a horse, and was dead before he could slit his wrists: a casualty of the evil, artless, stupid banalizers.

Recall what Witkacy said about the three basic engines of all human activity: In his play, it was the money that won. With the Nazis in 1939, it was power. But here in today’s United States, faced with our own wannabe Hitler, it is women that will prevail.

ICYMI

Our guest on the last Five 8 before Election Day was Dave Daley:

Show this PSA to your family members, neighbors, coworkers, and former friends who are planning to vote for Trump:

I was a guest on Media Watch, where we talked about Rough Beast:

And, on the lighter side, I was on the Legitimate Likes podcast with my friend Will Sebag-Montefiore and his awesome compatriots, ranking US presidents. Here is a clip:

Oh, and one more thing…I’ve created a Kamala 271 playlist. There are 47 songs:

Hang in there, my friends. Two more days until America takes out the trash!

Photo credit: False woman - Portrait of Mrs. Maryla Grosmanowa with Stanisław Ignacy WitkiewiczPolski: "Fałsz kobiety (Maryla Grossmanowa i autoportret)", pastel na papierze, 115,5 x 184 cm, Muzeum Narodowe, Warszawa.

Greg, you’re fascinating. This one from out-of-nowhere to me, is awe inspiring. Who knew? Well, apparently YOU. Thanks to your inquiring mind, we do too. Now onto Kamala music & your list of presidents….

Thanks for the enlightening story of Stanislaw Witkacy. I have to say that "Sunday Pages" has been the most enjoyable part of your weekly musings. It's the manner by which a bit of separation from the previous week's mostly irritating news is achieved. And it elevates the literary and artistic mode of seeing the world that daily life often avoids.

As for Huxley, how I have remembered him has less to do with Brave New World, but rather the means of his exit from living:

He took his final "trip" by ingesting LSD with the assistance of Mrs Huxley, and this might be apocryphal -- I heard it via a talk given by Dr. Richard Alpert, aka Baba Ram Dass -- his final word was singular.... "Extraordinary".... most likely uttered in that inimitable "British" way.

The final irony.... and why it has alway stuck in my memory... is the date:

November 22, 1963

https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/intoxication/miscellany/aldous-huxleys-lsd-death-trip