Dear Reader,

Knowing nothing about Raymond Chandler, the author of American detective fiction ne plus ultra, we might reasonably assume that he grew up in Los Angeles and watched the city change with the advent of the motion picture; that he once worked as a policeman or a detective himself, as the spy novelists Graham Greene, Ian Fleming, and John Le Carré all spent time with the British intelligence services; that he ran liquor during Prohibition; and that the “common” patois spoken by his characters, the colorful language of the street, was picked up from intimate familiarity with various and sundry degenerates.

None of those things are even close to being true.

Born in 1888 in Chicago, Chandler almost immediately moved to Plattsmouth, Nebraska, south of Omaha on the Missouri—and after his father, a feckless drunk, ran off, relocated with his Irish-born mother to the south of London. He spent his formative years in England and became a British citizen. Listening to the hard-boiled American badinage in his work, one would never guess that he was a graduate of Dulwich College, a well-regarded public school (in the British sense) that also produced P.G. Wodehouse and C.S. Forester. He didn’t even show up in L.A. until 1913—just in time for the 25-year-old to go fight with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War.

Upon his return to Los Angeles in 1918, Chandler began a relationship with Pearl “Cissy” Pascal. The pairing was unlikely to last because Cissy was 1) married, 2) stepmother to an army friend of Raymond’s, 3) disapproved of by his mother, and 4) eighteen years older. But the two were together until her death in 1954, an event Chandler mourned so passionately that he attempted suicide soon after.

Not that it was a perfect union. He would have affairs with many of the women in his life: his agent, his secretaries, wives and widows of writer friends. And like his father, he was an alcoholic. The mixing of business and pleasure and a tendency to drink on the job are attributes Chandler bequeathed to his greatest literary creation, the private detective Philip Marlowe, and suit that shamus as well as they do another womanizing lush of midcentury fiction, James Bond—but they did not serve him well in real life. At his fancy job working for an oil concern in the 1920s, he was an HR nightmare (or would have been, had their been HR departments before the New Deal), and his drinking and philandering eventually led to the termination of his employment.

Only when he was let go in 1931 did Chandler embark upon the literary career he’d been quietly nurturing since boyhood. When his first novel, The Big Sleep, was published in 1939, he was 51 years old—just a year younger than I am right now, and twice as old as many if not most debut novelists.

His behavior towards the women in his life informs the casual misogyny that permeates his work: “The Big Seep,” as the noir novelist Megan Abbott smartly phrases it, in her fantastic 2018 essay on the subject. It must be reckoned with.

“What fascinates and compels me most about Chandler in this #MeToo moment are the ways his novels speak to our current climate,” Abbott writes. “Because if you want to understand toxic white masculinity, you could learn a lot by looking at noir.”

She continues:

Loosely defined, noir describes the flood of dark, fatalistic books and films that emerged before, during, and especially after World War II. As scholars like Janey Place have pointed out, this was an era when many white American men felt embattled. Their livelihoods had been taken away—first by the Depression, then by the war, and then by the women who replaced them while they were off fighting. Into this climate noir flowered: Tales of white, straight men—the detective, the cop, the sap—who feel toppled from their rightful seat of power and who feel deeply threatened by women, so threatened that they render them all-powerful and blame them for all the bad things these straight white men do. Kill a guy, rob a bank—the femme fatale made me do it. These novels simmer with resentment over perceived encroachment and a desire to contain female power.

Depression-era detectives, real and imagined, were not “woke,” and expecting—or, worse, demanding—that they retroactively adopt modern standards of acceptable male behavior (that, incidentally, too many men in 2024 have yet to adopt) is both ridiculous and boring. Plus, as Abbott says, we can learn from it.

Reading The Big Sleep, which is narrated by Marlowe—just as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is narrated by Marlow—I see an honorable but lonely man struggling to explicate human nature. He wants to break everything down to the tiniest detail but can’t. He errs on the side of distrust. He dons emotional armor to steel himself against the female charms he’s otherwise susceptible to. He is a straight white man who abides by a rigid moral code developed by straight white men, and anyone who isn’t a straight white man simultaneously fascinates and befuddles, attracts and repulses him. He is more sensitive than he lets on; I would characterize Marlowe’s masculinity as more bewildered than toxic.

Again: there is much to learn, good and bad, about men, and manhood, and masculinity, from these pages.

In person, Chandler was funny, clever, well-acquainted with people of all manner of backgrounds, and highly observant. He was also clinically depressed, painfully judgmental, deeply insecure, and cynical as hell. One can be highly observant without being cynical, but one cannot be cynical without being highly observant. As Ambrose Bierce quipped, the cynic is “a blackguard whose faulty vision sees things as they are, not as they ought to be.”

Chandler might call this realism. In his 1950 essay, “The Simple Art of Murder,” a discourse on detective fiction that is the introduction to an anthology of his short stories, he writes:

The realist in murder writes of a world in which gangsters can rule nations and almost rule cities, in which hotels and apartment houses and celebrated restaurants are owned by men who made their money out of brothels, in which a screen star can be the finger man for a mob, and the nice man down the hall is a boss of the numbers racket; a world where a judge with a cellar full of bootleg liquor can send a man to jail for having a pint in his pocket, where the mayor of your town may have condoned murder as an instrument of money-making, where no man can walk down a dark street in safety because law and order are things we talk about but refrain from practicing; a world where you may witness a hold-up in broad daylight and see who did it, but you will fade quickly back into the crowd rather than tell any one, because the hold-up men may have friends with long guns, or the police may not like your testimony, and in any case the shyster for the defense will be allowed to abuse and vilify you in open court, before a jury of selected morons, without any but the most perfunctory interference from a political judge.

A little too on the nose, right? That paragraph was written three quarters of a century ago, but in it, we glimpse Vladimir Putin, and Donald Trump, and Matt Gaetz, and Clarence Thomas, and Rudy Giuliani, and any one of a thousand witnesses to the crimes of Jeffrey Epstein and Sean Combs. Does that say something about all men? About human nature in general? Or it is a strictly American phenomenon? Captain Gregory, the head of the Missing Persons Department in The Big Sleep, makes no bones about it, telling Marlowe:

Being a copper I like to see the law win. I’d like to see the flashy well-dressed muggs like [mobster] Eddie Mars spoiling their manicures in the rock quarry at Folsom, alongside of the poor little slumbred hard guys that got knocked over on their first caper and never had a break since. That’s what I’d like. You and me both lived too long to think I’m likely to see it happen. Not in this town, not in any town half this size, in any part of this wide, green and beautiful U.S.A. We just don’t run our country that way.

We didn’t run the country that way in 1939, we don’t run it that way in 2024, and 2025 looks like it will be a banner year for flashy well-dressed muggs. “It is not a fragrant world,” Chandler says in his essay, “but it is the world you live in.”

Few writers wrote about our unfragrant world as giftedly as Raymond Thornton Chandler. There is some Hemingway in his voice, and some Hammett in his sensibilities, but no one is quite like him. On almost every page of The Big Sleep, there is some poetical passage or paragraph, a clever witticism or creative metaphor: the sort of top-drawer prose not usually given to detective fiction, that leaps out from the page.

This is a throwaway line that Chandler makes beautiful:

Under the thinning fog the surf curled and creamed, almost without sound, like a thought trying to form itself on the edge of consciousness.

The second time Marlowe encounters the troubled Carmen Sternwood, at what winds up being a murder scene, he tells us:

She was wearing a pair of long jade earrings. They were nice earrings and had probably cost a couple of hundred dollars. She wasn’t wearing anything else.

His description of Vivian Sternwood’s quarters, with its contrasts in light and darkness, and his use of the weather to foreshadow the thunder and lighting to come, is superb:

This room was too big, the ceiling was too high, the doors were too tall, and the white carpet that went from wall to wall looked like a fresh fall of snow at lake Arrowhead. There were full length mirrors and crystal doodads all over the place. The ivory furniture had chromium on it, and the enormous ivory drapes lay tumbled on the white carpet a yard from the windows. The white made the ivory look dirty and the ivory made the white look bled out. The windows stared towards the darkening foothills. It was going to rain soon. There was pressure in the air already.

Finally, there is this beauty, which is engraved on his tombstone:

Dead men are heavier than broken hearts.

Here is the opening paragraph of The Big Sleep:

It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark blue clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.

Note how much information is conveyed in those five sentences: We know the time of day, the season, the weather, and the forecast. We have a sense of the terrain. We know what he’s wearing—everything dark, everything black (although blue and black, my mother always said, do not match), but patterned socks that suggest he doesn’t take himself too seriously. We know from his decision to include “sober” among the four adjectives to describe himself that there are plenty of occasions when he is anything but that. We know he’s ashamed of his drinking. We know his profession. We know he has a keen eye for detail. We know he works alone. And we know he’s a fish out of water—dressed to meet someone with old money the way he thinks someone with old money would want him to dress. Four million dollars in 1939 is equivalent to $90 million today.

In the second paragraph, Chandler reveals the theme of the novel and hints at the plot—although we don’t know it yet. He’s thrown a fastball right over the plate, and we just let it go by:

The main hallway of the Sternwood place was two stories high. Over the entrance doors, which would have led in a troop of Indian elephants, there was a broad stained glass panel showing a knight in dark armor rescuing a lady who was tied to a tree and didn’t have any clothes on but some very long and convenient hair. The knight had pushed the visor of his helmet back to be sociable, and he was fiddling with the knots on the ropes that tied the lady to the tree and not getting anywhere. I stood there and thought that if I lived in the house, I would sooner or later have to climb up there and help him. He didn’t really seem to be trying.

What Marlowe will do, over the course of the novel’s 231 pages, is, basically, insert himself into the stained glass panel to help rescue the lady. The noir detective, after all, is just a modern twist on the white knight archetype from the age of chivalry, going off on perilous adventures at the behest of his lady. He’s not in it for sex. He’s not in it for money, not really. He’s in it to restore balance, to right the wrongs. He’s in it for honor.

“Marlowe is nearly celibate, avoids carrying a gun, and only shoots a man once,” Abbott points out. “His isolation from others is profound. Forever unattached and seemingly friendless, he feels increasingly out of place in a changing Los Angeles.” He is the knight in the stained glass panel.

Chandler was well aware of the kind of character he sought to create in Philip Marlowe. It’s all very intentional. The guy’s allusive last name, after all, is the same as that of an Elizabethan playwright, much celebrated at Dulwich College, who was no stranger to the seedy side of life. In “The Simple Art of Murder,” he details who exactly the noir detective must be:

In everything that can be called art there is a quality of redemption. . . [D]own these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero; he is everything.

He is a relatively poor man, or he would not be a detective at all. He is a common man or he would not go among common people. He has a sense of character, or he would not know his job. He will take no man’s money dishonestly and no man’s insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him. He talks as the man of his age talks—that is, with with rude wit, a lively sense of the grotesque, a disgust for sham, and a contempt for pettiness.

The story is this man’s adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure.

Megan Abbott says she is drawn to Chandler “because the world he brings to life so vividly is a world I understand, especially now. It’s a world of peril, a troubled and troubling place where it feels harder and harder to make things right.”

That was true in 2018, and even more so now. In a world of crooked politicians, corrupt judges, captured corporate media, cowardly attorneys general, and capitulation all around; an artless world, out of balance and off kilter, that seems increasingly divorced from reality; a world that elevates the simple and the stupid, the profane and the profiteering, the inhuman and the inhumane—in this world, we need someone unafraid to speak truth to power, to hold the bad guys accountable, to make things right, to jump headlong into the stained glass window and free us from our bondage. To save the day.

Do Philip Marlowes only exist in works of fiction? And if so, does the fact that our alternative-truth reality has become a work of fiction mean that a hero will one day emerge, and put things right, and save us all, for $25 a day plus expenses?

The evidence suggests otherwise. Jim Comey was not that person. Neither was Robert Mueller, or Christopher Wray, or Merrick Garland, or even Jack Smith—although he came the closest. And yet we ache for this salvation. We yearn for justice. We are so desperate for these Marlovian qualities that we have collectively projected them upon a cold-blooded murderer.

Speaking of which: the title of The Big Sleep is realized in the last pages of the book. It’s a slangy way of saying Death:

What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? …You were dead, you were sleeping the big sleep, you were not bothered by things like that….You just slept the big sleep, not caring about the nastiness of how you died or where you fell. Me, I was part of the nastiness now.

But the phrase “the big sleep” also suggests a sort of suspended animation, an un-wokeness, a perpetual bad-dream state, a walking nightmare from which all of us are trying to awaken. How did Chandler put it? Like a thought trying to form itself on the edge of consciousness.

One day the thought will form. One day we will all of us wake up from the big sleep.

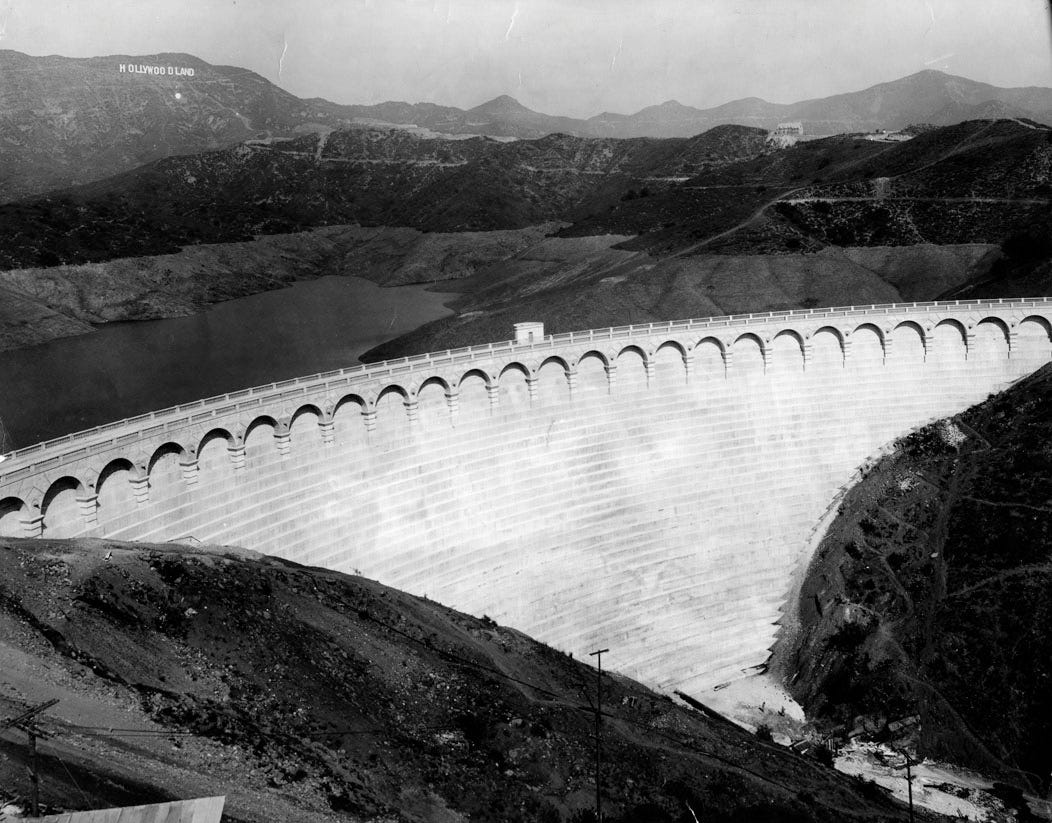

Photo credit: Water & Power Museum. Front view of Mulholland dam in the Hollywood Hills, the most beautiful of a score of storage basins in Los Angeles’ water system, 1929. The HOLLYWOODLAND sign can clearly be seen in the background.

Nice to see you broadening your cultural horizons, Greg. It's hard to go wrong with Chandler, for all the reasons you demonstrated here.

I had the privilege during my earlier days in the screen trade to be introduced to Billy Wilder, by then involuntarily retired but still involved in things. I got a post-graduate education in the movies over two years of lunches with him in his office over in Beverly Hills, listening to his stories (I think got the job because I was the only person he knew who hadn't heard them all 10,000 times). He told me about working with Chandler when they wrote "Double Indemnity." His most withering comment was "The man had no problem creating pictures with words but he couldn't use pictures as words." That's a common failing with writers who aspire to the movies; they think a screenplay is "literature," when - as Wilder put it - "A screenplay is a blueprint and a screenwriter is a draftsman." "Movies" is a contraction of "moving picture," the method by which the story is told. He told me the fact I was a photographer was going to be very useful in my screenwriting and he was right - I still tell aspiring screenwriters that the road to success is to go over to Harry's Cameras and get a good used Nikon.

But one of the reasons Chandler has been adapted so well in the movies is because his work is easy to adapt. The pictures just flow, as you demonstrated so well. If you look at the opening scene of "The Big Sleep" on the screen, it relates to everything in that opening paragraph.

Happy Sunday, Greg! This was such wonderful reading for a Sunday morning. Took me back 50 years to all of the greats: Chandler, Hammett, and (in the same breath!) Hemingway. And made me think about all of the books and films since that bear their imprint (Scorsese's Mean Streets, Polanski's Chinatown, Banville's Quirke books. . .).

For fun, you might watch this excerpt of an interview from the 30th anniversary Blu-ray edition of Miller's Crossing, with Megan Abbott talking to Joel and Ethan Coen about noir and their film. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LN-iXfllAg8

And I don't think there is a hero out there for us. I think we will have to be that hero ourselves.