Dear Reader,

This week, Ted Cruz came out against doors.

In Uvalde, Texas, a few hours after the gruesome slaughter of elementary school children by an 18-year-old with two AR-15s and enough ammunition to occupy downtown Houston, the mendacious GOP Senator explained to a gaggle of reporters that the real scourge on society was not weapons of war, not easy access to guns and ammo, not lax laws that allow customers that young to buy semi-automatic rifles but not a six-pack of Coors Light, not pusillanimous policeman who might as well have been passing around a box of donuts while kids bled out, but rather entrances and exits. It’s not the guns, Ted Cruz argued, with feigned indignance; it’s the doors:

Do you want to talk about how we could have prevented the horror that played out across the street? Look, the killer entered here the same way the killer entered in Santa Fe: through a back door, an unlocked back door. I sat down at roundtables with the families from Santa Fe, and we talked about what we need to do to harden schools, including not having unlocked back doors, including not having unlocked doors to classrooms, having one door that goes in and out of the school, having armed police officers at that one door.

And just like that, Ted Cruz established a new standard for gaslighting. This was the Mona Lisa, the Wilt Chamberlain 100-point game, of pure bullshit. Twitter let him know it. So did the media. So did his fellow restaurant diners. Far from causing him shame—the ability to feel shame is a feature the Rafael Edward Cruz model does not support—Ted Cruz almost certainly left that presser pleased with himself. He’d done his NRA whoremasters proud.

Time will tell if Uvalde will prove an actual turning point in America’s struggle against the gun lobby/ NRA/ Russian asset/ 2A fetishist minority, or Sandy Hook 2.0, another grim milestone on the road to our collective doom. But when I heard about Ted Cruz lashing out against the doors, I imagined Ted Cruz lashing out against The Doors. And why not? Jim, Ray & Co. have about as much to do with the massacre at Uvalde than Pella or Andersen—which is to say, not a damned thing.

But the more I thought about my favorite Doors song, “The End,” the more appropriate it seemed to the occasion. Uncannily, eerily appropriate.

The Doors took their rather clumsy band name from a book by Aldous Huxley, which took its title from an aphorism by the inscrutable William Blake: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” They wanted to present as profound, unknowable. Growing up, I found them pretentious and overrated; I had a theory that the classic rock stations played them so much because, unlike the Beatles, the Stones, Pink Floyd, and Led Zeppelin, The Doors were American. As I get older, however, I find that, for whatever reason, I enjoy them more, and the British acts less.

In Ray Manzarek, The Doors boasted an elite musician and songwriter. But it was Jim Morrison that took the enterprise to a whole other level. When he was lucid enough to perform, he was a fantastic front man, charismatic, broodingly handsome, sexy. (As a guy with a low singing voice, I always appreciated his baritone among the falsetto shrieks of FM radio.) He was certainly an artist, among the more tortured we’ve had. He went from “young, talented, and hot” to “fat Elvis dead on the toilet” in just four and a half years. He died at age 27—like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse—in a Paris bathtub in 1971. He’s buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, and his resting place remains an attraction for tourists, some of them prone to vandalism. (There is a conspiracy theory that “they” had him killed, because his father was the rear admiral who commanded the U.S. naval forces during the Gulf of Tonkin incident. But I don’t think the death of a guy this fucked up is much of a cold case.)

“The End,” the last track on the band’s eponymous first album—recorded in August of 1966, when Morrison was 22—is, to me, their pièce de résistance. The song is shrouded in mystery, mostly because Morrison was tripping balls when he wrote the lyrics. For me, the song cultivates a mood. It begins quietly, simply. The sitar-like electric guitar taps into something primal and ancient, sacred and profane, as it violates the rules of the key signature. Just as you settle into the patient, hypnotic vibe, the tambourine shakes, sounding for all the world like a rattlesnake, alerting you to the hazards to come.

Everything is here: divinity, danger, terror, rage, truth, sadness, pain, gratitude, nostalgia, escape, love. Like the opera section of “Bohemian Rhapsody,” the lyrics are meant to be absorbed as a whole, not parsed. They serve to enhance the mood. But when we do stop and analyze the words, “The End” is about a man bidding à Dieu to the world before he goes out and commits an unspeakably violent act. This is why it works so effectively on the soundtrack to Apocalypse Now.

It begins lucidly enough, with lines said to be written by Morrison to commemorate his girlfriend leaving L.A.:

This is the end,

Beautiful friend.

This is the end,

My only friend, the end

Of our elaborate plans, the end

Of everything that stands, the end.

And then it suddenly gets very, very dark:

No safety or surprise, the end.

I’ll never look into your eyes again.

There is no mistaking the finality of those lines. Either he does not expect her to return, or he does not expect to survive what he’s about to do. After a few more verses and juvenile rhymes ( bus / us, West / best), we come to the infamous spoken-word section in the middle, where the action takes place. As mentioned, the lines feel eerily appropriate to the tragic events of this week, if not outright prophetic:

The killer awoke before dawn.

He put his boots on.

He took a face from the ancient gallery,

And he walked on down the hall.

The “face” supposedly belongs to Oedipus.

He walked on down the hall,

And he came to a door,

And he looked inside.

“Father?” “Yes, son?”

“I want to kill you. Mother? I want to…”

In the original recording, Morrison completes the thought: “…fuck you.” That wouldn’t even fly now, let alone in 1966. So it was cut, subsumed into the garbled, orgiastic frenzy at the climax, which ends with one word repeated six times, in a low voice, as if growled by a lesser demon issuing commands: Kill, kill, kill, kill, kill, kill.

The slaughter complete, the demon expelled, the rage sated through violence, the narrator contemplates what he’s done. The music resumes its calm, hypnotic quiet. The last lines of the song leave little doubt that the person he’s addressing, his “beautiful friend,” is now dead—and that he will soon join her in eternal slumber, Romeo and Juliet in the tomb:

It hurts to set you free,

But you’ll never follow me.

The end of laughter and soft lies.

The end of nights we tried to die.

This is the end.

Was Jim Morrison a poet? I don’t know where the heavy drugs end and Jim Morrison begins. But if poetry is the ability to tap into the collective consciousness and give it voice, then yes, Jim Morrison was a poet. Having a father who directly escalated the Vietnam War made him uniquely qualified to sing about such horrors: to absorb and to process, through song, the pain of his generation—and, it seems, the pain of generations to come, generations that have endured the violent horrors of Sandy Hook and Parkland, Santa Fe and now Uvalde. Are not the greatest poets prophets, too?

If internet rumors are to believed, Morrison was listening to old Doors LPs in Paris the night he died. The last thing he heard before breaking on through to the other side was “The End.”

“The end of nights we tried to die” means that now, tonight, the attempt to die will be successful. So it was that Jim Morrison left us, too soon.

This is the end.

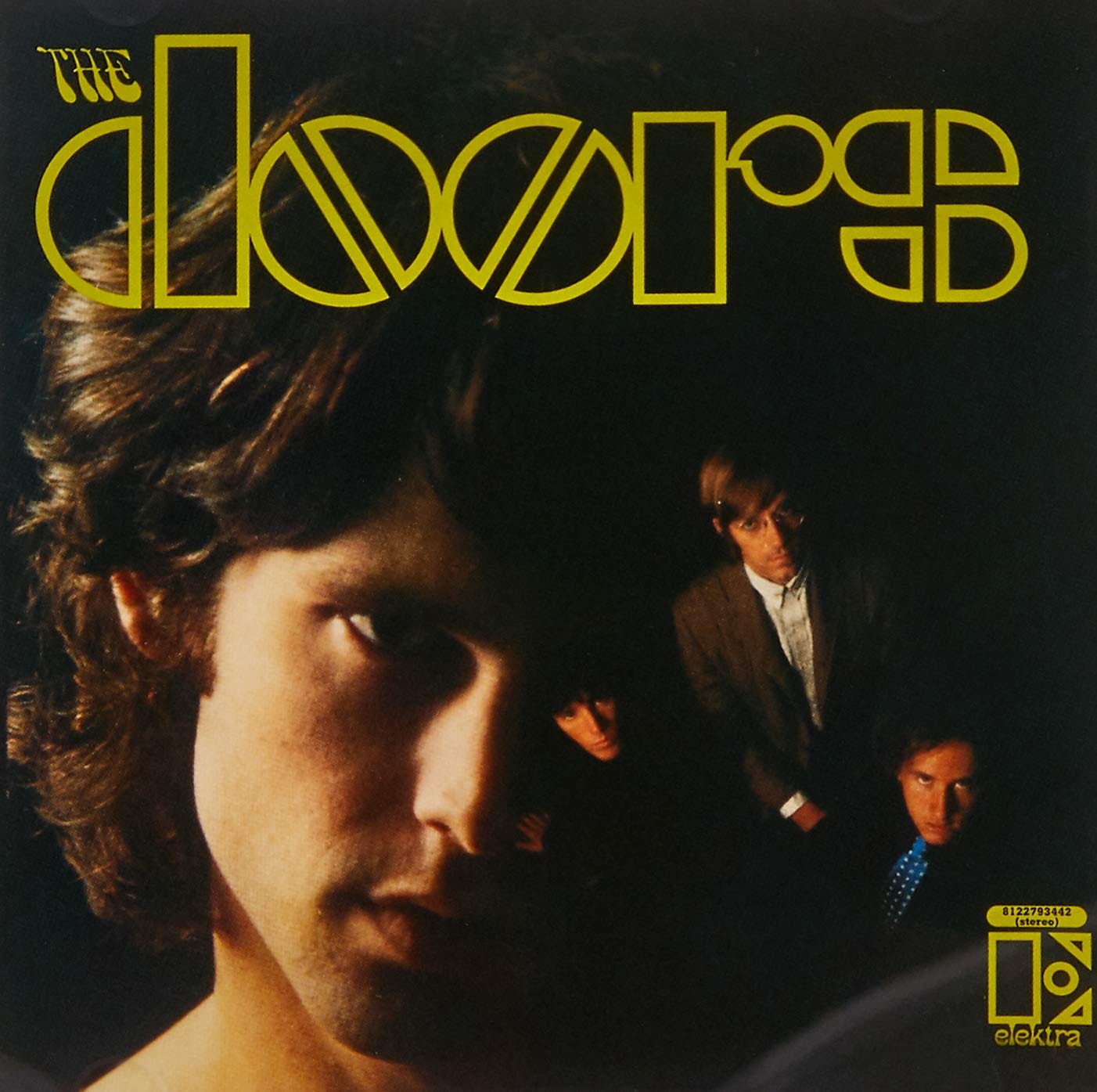

Photo credit: cover of the first Doors LP.

100%. And this whole clusterfuck is an end. I think the FDA and CDC can declare AR rifles a hazard to humans and ban them that way. Fuck Congress. And if not this way take over Remington and Ammo Corp for defense use

I never exactly put the words/meaning of the song together so clearly as you have now. Chilling.