Sunday Pages: "The Great Gatsby" at 100

A foreword (forward!) to a centennial edition of F. Scott Fitzgerald's Jazz Age classic

Dear Reader,

Last night, my last in Baltimore, I took a walk along the Inner Harbor. It was the first time since I arrived at the coin show that I’d ventured beyond the hotel and convention center, and I was badly in need of some fresh air.

People were out and about. The weather was muggy, even hot—according to my phone, the temperature was north of 80 degrees. But the sun was going down now, and a cool breeze blew in from the water, where off in the distance you could see the Domino Sugar factory from the opening credits of The Wire.

There was a lot on my mind. Some of it was positive: the launch of the new show on our Five 8 network (The Five 8 1/2, cohosted by the great team of Nadine Smith and Lisa Graves, which premieres on Wednesday April 16) and the release of my new Gatsby edition (of which more shortly). But I was mentally exhausted, and thus unable to enjoy the good stuff, because, I mean, I don’t know if you read the news, but heavens to Murgatroyd has this been a bleak week. Behind all the couchfucker jokes and burning Tesla memes and cracks about Secretary of Defense Johnnie Walker Red is a heightening sense of dread, and grief, and despair—what eventually becomes of pent-up rage.

Then, in front of me, I saw a sign for Fort McHenry. A simple brown street sign pointing to a right turn.

And I started to cry.

And all at once, the negative emotions drained out of me. I felt a surge of what can only be called defiant certitude. The whole trip has been a microcosm of my current mental state, I realized. I was so stuck in a limited space—inside, online—that I’d forgotten where I was: what historic ground I was treading upon.

This is where, on September 14, 1814, a local lawyer, after witnessing the British bombardment of the harbor in the Battle of Baltimore—in which the Americans repulsed the Royal Navy and slew the English Commander—was moved to write a poem called “The Defense of Fort M’Henry.” Part of that poem became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

And all I wanted to do was shout at Trump and Musk and the other fascist pigs: THE BANNER STILL WAVES, MOTHERFUCKERS. But I was by the Aquarium and there were too many kids around, so I held my tongue. Even so, the feeling remained—and remains.

Not only that, but the poem about Fort McHenry was written by one Francis Scott Key, distant cousin and namesake of the very writer whose book I am now reissuing. A sign? A coincidence? I don’t know, but it eased my mind nonetheless.

THE BANNER STILL WAVES, MOTHERFUCKERS!

Last month—which now feels like a semester and a half ago—I produced a book of “Sunday Pages” essays on tyranny and literature, The Age of Unreality. There were three main motivations for doing this.

First, I was, and continue to be, afraid that Elon Musk and his babyfaced DOGEmites will at some point blot out the internet—whether through buying and destroying Substack or just SpaceX-ing it and making it explode like a shoddy Tesla—and I wanted to safeguard my writing. That essay book was a very elaborate way of “backing up my work.”

Second, ego—and, I suppose, vanity. I just wanted the book to exist, so I made it exist, and now, ta-da, it exists.

And finally, it was an experiment. Could I take my small imprint, Four Sticks Press, and make it into a viable operation? Back in the late summer / early fall, when it looked like Biden passing the baton to Kamala Harris was a genius move, and the MVP would cruise to a victory over the rapist mobster with the rap sheet, I figured my work here was done. We were gonna prevail! With the Rough Beast slain once and for all, I would have to find something else to do. And I got the idea to take some of these “Sunday Pages” essays on literature that is already in the public domain, and put out books with my pieces and the original text and maybe some other fun stuff.

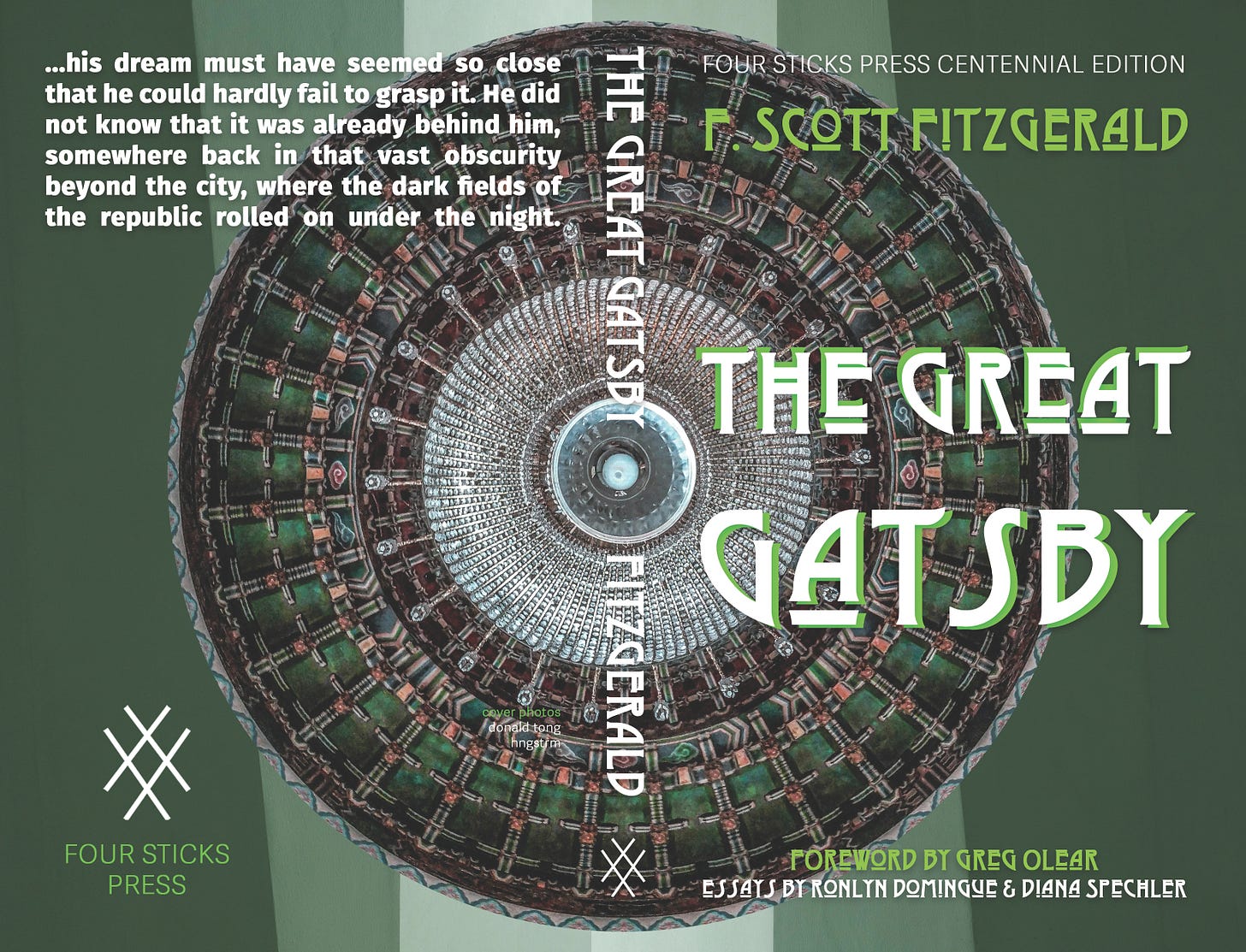

The Great Gatsby is one of my favorite novels, so I figured I’d start with that. And then I saw that the centennial of its publication is April, 2025—next month. And I took that as I sign. I appropriated an essay I’d written back in 2013, and I set about writing a foreword (which was harder than I thought), and I recruited two of my favorite writers, my friends Ronlyn Domingue and Diana Spechler, to contribute essays as well. And I put in some footnotes on the actual text.

So I’m pleased to announce that the first Four Sticks Press Centennial Edition is now in print. Right now it’s on Amazon, but it should also be available at bookstores…ask them to order it via ISBN (979-8985931976). The e-book will be available shortly, too. (Amazon says there is a hardcover, but there is no sanctioned hardcover.)

There’s going to be a lot of stuff written about Gatsby in the next four weeks. If you feel inspired to read the novel and are hunting around for a copy, I humbly ask you to purchase mine. Thank you!

And now, here is the foreword to the Four Sticks Press Centennial Edition:

Foreword: Gatsby at 100

There was a time when I believed—when I insisted—that The Great Gatsby was the Great American Novel. I have since decided that Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age masterpiece, published 100 years ago this April, is not broad enough in scope to deserve that accolade. How can a novel about rich white people on Long Island—a sort of Real Housewives of East Egg, or a lost season of The White Lotus—be comprehensively “American” enough to wear the crown?

Even so: if The Great Gatsby isn’t the Great American Novel, it is certainly a Great American Novel. It’s also, indisputably, a Great American Novel. Fitzgerald manages to stuff so many peculiarly American fascinations into the book’s economical 47,093 words—old money, sudden wealth, fame, name-dropping, sports, gambling, snobbery, slumming, organized crime, reinvention, deceit, gossip, violence, sex (straight and gay), infidelity, fancy automobiles, guns, swimming pools, Wall Street, racism—that even now, a full century after its publication, Gatsby feels as relevant as when Coolidge was in the White House, booze was illegal, and the Nazis were still a fringe party.

Consider: Our current president is a Jay Gatsby gone bad; he apprenticed at the foot of his own mobbed-up Meyer Wolfshiem, Roy Cohn; the Cabinet is littered with abusive, white supremacist Tom Buchanans; Daisy would fit right in at Mar-a-Lago; East Egg is not unlike Palm Beach. Spoiled rich people still behave the same spoiled way and remain objects of our voyeuristic curiosity—only now, we get to “keep up” with them on reality TV. None of Fitzgerald’s character names are aurally anachronistic; doesn’t Jordan Baker sound like she could be a 19-year-old TikTok influencer? And even today, despite the benefit of Google and a full century’s worth of newer writing, you would be hard-pressed to find a better descriptor of the MAGA quintessence than what Fitzgerald wrote about the Buchanans: “They were careless people…they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Then again, should we really be surprised? It’s the Twenties, after all!

What I particularly love about this book is that unlike, say, Moby Dick—another perennial Great American Novel candidate—Gatsby is accessible. Meaning, it’s not hard to read. The writing is elegant and smooth but not fancy. Your average eighth-grader could make it through all nine chapters and have at least a rudimentary understanding of the plot.

But the simplicity of the prose belies the novel’s complexity. I’ve read The Great Gatsby cover to cover a dozen times, and with each reading, my appreciation and understanding deepen. Gatsby contains multitudes. There’s always more there than meets the eye. And, as the essays in this centennial edition demonstrate, every reader brings his, her, or their own unique perspective to the source material.

Like all of Fitzgerald’s fiction, The Great Gatsby is semi-autobiographical. But ten decades after publication, it matters little that most of the characters are based on actual people he knew in real life. All of them are long dead, and with the exception of the model for Jordan, Edith Cummings—a golfer who won the U.S. Women’s Amateur and was the first female athlete to grace the cover of Time magazine—none of them was famous independent of him. We know them now only because of their association with Fitzgerald and Gatsby.

But even in 1925, the detective game of figuring out who was based on whom was irrelevant; Gatsby is not a memoir, or even a true roman à clef; in fiction, all that matters is the finished product. For me, the less I know about the IRL inspirations, the better. I don’t like anything adulterating the images of the characters that I’ve formed in my head. That the alluring Chicago socialite Ginevra King and her polo-playing nepo baby husband Bill Mitchell, the models for the Buchanans, look quite a bit like how I picture Daisy and Tom—their passport photos are on her Wikipedia page, if you’re interested—is more a testament to Fitzgerald’s keen powers of observation than his fidelity to “real” life.

With that said, Fitzgerald did have a lot in common with his greatest (ahem) literary creation. Like Jay Gatsby, he came from a broken, broke family in the Middle West. Like Jay Gatsby, he was blindingly ambitious. Like Jay Gatsby, he fell hard for a rich debutante who loved him but wouldn’t marry him. Like Jay Gatsby, he used that rejection as professional motivation. Like Jay Gatsby, he set out to make his fame and fortune: to prove himself worthy of said rich debutante. And like Jay Gatsby, he succeeded beyond his wildest dreams—but also, tragically, failed.

And yet temperamentally, the historical Fitzgerald was closer to Nick Carraway, the book’s sensitive, not-as-reliable-as-he-thinks-he-is narrator. Both of them were army veterans from West of the Mississippi. Both had fathers who worked in the furniture business. Both were smart, observant, and witty; both were Ivy Leaguers; both were marvelous writers. Both regarded the decadent Long Island party lifestyle with contempt, even as they merrily participated in it. Both would never in a million years call someone “old sport.” It’s almost like Jay and Nick are different iterations of the same person, like some Jazz Age version of Severance: Gatsby the outie, Carraway the innie, never able to fully reintegrate.

The working title for what became his debut novel, This Side of Paradise—a semi-autobiographical chronicle of his college days at Princeton: a sort of proto-Catcher in the Rye, written in 1918, in a manic creative burst three months before he joined the army—was The Romantic Egoist, and that about sums up the young Scott Fitzgerald. He was romantic and self-absorbed, if not beautiful and damned, and his ambitions both nuptial and literary had been so thoroughly thwarted that he vowed, as he sent the revised manuscript off to Scribner’s, that if he failed one more time—if this attempt, too, was a flop—he would throw himself off the nearest bridge. But This Side of Paradise was not a flop. On the contrary: it was a runaway bestseller and a cultural phenomenon, and it made F. Scott Fitzgerald, in 1920, at the tender age of 23, both a household name and a vast fortune.

In those heady days, Fitzgerald “saw the improbable, the implausible, often the ‘impossible,’ come true,” as he would later recall. “It seemed a romantic business to be a successful literary man….Of course within the practice of your trade you were forever unsatisfied—but I, for one, would not have chosen any other.”

The Fitzgerald of a hundred years ago was hopelessly romantic, naïve, and green as the light on Daisy’s dock—and this was obvious at a glance. “Scott was a man then who looked like a boy with a face between handsome and pretty,” his friend Ernest Hemingway wrote in his Paris memoir, A Moveable Feast, about meeting him in 1925. “He had very fair wavy hair, a high forehead, excited and friendly eyes and a delicate long-lipped Irish mouth that, on a girl, would have been the mouth of a beauty. His chin was well built and he had good ears and a handsome, almost beautiful, unmarked nose. This should not have added up to a pretty face, but that came from the coloring, the very fair hair and the mouth. The mouth worried you until you knew him and then it worried you more.”

Hemingway was right to worry. Fitzgerald could never quite get his shit together. The talent was greater than the output. He was a phenom who didn’t live up to his boundless potential—the literary equivalent of a starting pitcher with great stuff but lousy control, who gave you here and there a few innings of uncanny brilliance, interspersed with long stretches where he labored just to get the ball over the plate. He would have been a cautionary tale, a novelist “What If,” had it not been for The Great Gatsby—the one shining season when our otherwise-erratic pitcher turned in a Dwight-Gooden-in-1985-level campaign. We might say that F. Scott Fitzgerald is the Dwight Gooden of letters (or, if you’re a Mets fan, that Dwight Gooden is the F. Scott Fitzgerald of baseball).

At least, that’s how I see it. And I’m not the only one who feels this way. “A writer like me,” Fitzgerald told a New York Post reporter in 1936, reflecting on what might have been, “must have an utter confidence, an utter faith in his star. It’s an almost mystical feeling, a feeling of nothing-can-happen-to-me, nothing-can-harm-me, nothing-can-touch-me. Thomas Wolfe has it. Ernest Hemingway has it. I once had it. But through a series of blows, many of them my own fault, something happened to that sense of immunity and I lost my grip.”

Hemingway said it best: “His talent was as natural as the pattern that was made by the dust on a butterfly’s wings,” he wrote, in 1960. “At one time he understood it no more than the butterfly did and he did not know when it was brushed or marred. Later he became conscious of his damaged wings and of their construction and he learned to think and could not fly any more because the love of flight was gone and he could only remember when it had been effortless.”

Really, it’s a minor miracle that Scott Fitzgerald was able to finish Gatsby at all—let alone churn out a novel this good and this enduring. After the success of This Side of Paradise, he had more than enough money to support Ginevra King. But she was already Mrs. Bill Mitchell, her father detested him, and it couldn’t possibly work out. And so, as a consolation prize, he married Zelda Sayre, a Southern belle from Montgomery he’d met while stationed in Alabama during the war. It proved a disastrous pairing: two creative geniuses, laughably immature, each jealous of the other, both emotionally unstable, both blackout drunks with suicidal tendencies. Scott and Zelda were a hot mess—a Jazz Age Kurt and Courtney. They enabled one another’s bad behavior, and as a result, neither produced as much as they might have otherwise.

Tempting as it is to portray Fitzgerald as yet another mediocre white man who steals a woman’s work and claims it as his own, I don’t hold with the theory that Zelda wrote most of The Great Gatsby. The themes of the book are clearly his; the characters, as discussed, were obviously based on people he’d known before he met her; and the prose style is the same as what we read in “The Crack-Up,” his fascinating and ahead-of-its-time mini-memoir, which was written when she was institutionalized. He did not Watson-and-Crick his wife. Now, did Zelda help him? No doubt. His editor, the great Maxwell Perkins, also played an outsized role in cutting and polishing the finished emerald, making sure the green light shone this brilliantly. But that’s how it works with novels. Trusted early readers make suggestions. Good editors edit. The author gets the credit, but the author is also the one who must face, alone, the book reviews and the royalty statements—an unpleasant experience even when good, and when bad, potentially ego-destroying.

In the case of The Great Gatsby, the reviews were mostly positive—Hemingway cites one by Gilbert Seldes, a well-known book critic, “that could not have been better. It could only have been better if Gilbert Seldes had been better.” Commercially, however, Gatsby was a disappointment. In the 15 years between its publication in 1925 and Fitzgerald’s death in 1940, royalties from the book totaled some $5,000. Adjusted for inflation, that’s…still not a lot of money. Only after his death in 1940, when the Council on Books in Wartime decided to include Gatsby in the Armed Services Editions catalog of titles distributed to U.S. soldiers during the Second World War, did Gatsby become great.

In the last few years of his life, Fitzgerald earned little from any of his novels. For the entire year of 1936, when he was trying to stay sober and writing “The Crack-Up” for Esquire and giving humiliating interviews to the New York Post, his book royalties, for Gatsby plus everything else, came to a grand total of eighty bucks. That’s $1841.57 in today’s dollars—roughly an average month’s rent. By then, the early windfall had run out, the creative well was dry, Zelda was living in a sanitarium in North Carolina, and he was holed up in a cheap Asheville hotel, to be close to her. As a public figure, Fitzgerald was widely regarded as passé, a has-been, an artifact from a bygone age—worse, from a decadent decade that had nothing to offer a nation suffering through the Great Depression.

He was, in a word, sunk. “Now the standard cure for one who is sunk is to consider those in actual destitution or physical suffering—this is an all-weather beatitude for gloom in general and fairly salutary daytime advice for everyone,” Fitzgerald wrote. “But at three o’clock in the morning, a forgotten package has the same tragic importance as a death sentence, and the cure doesn’t work—and in a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning, day after day.”

At the end, Fitzgerald was living in Hollywood with a British gossip columnist. He managed to stay sober for a solid 12 months while he worked on The Last Tycoon, but did not live long enough to see it through. Years of heavy drinking and ill health caught up to him. He died of a massive heart attack in 1940, four days before Christmas. He was just 44 years old.

Much has changed in the 85 years since his death. The Nazis were stamped out in Germany, only to re-emerge, eight decades later, in the United States (thus defying Fitzgerald’s adage that there are no second acts in American lives). The Great Gatsby became a perennial best-seller and joined the canon of great American fiction. But the novel itself, as an art form, has become less central to the popular culture—regarded, in many circles, as nothing more than a blueprint for the inevitable film adaptation. This Fitzgerald predicted:

I saw that the novel, which at my maturity was the strongest and supplest medium for conveying thought and emotion from one human being to another, was becoming subordinated to a mechanical and communal art that, whether in the hands of Hollywood merchants or Russian idealists, was capable of reflecting only the tritest thought, the most obvious emotion. It was an art in which words were subordinate to images, where personality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration. As long past as 1930, I had a hunch that the talkies would make even the best selling novelist as archaic as silent pictures.

His antipathy towards motion pictures, I think, is a bitter byproduct of his own failure to adapt to that medium. He was a lousy screenwriter. Even Gatsby, short as it is, with its bevy of memorable characters and solid plot, resists film treatment because of its structure. The denouement is too long and too internal, which works wonderfully in a novel but makes for an anticlimactic movie—even one where the title character is played by peak Robert Redford.

But Fitzgerald had a point about the continuing obsolescence of novels. As a novelist myself, I find this cause for concern. Marking the centennial of its publication on my calendar, I wondered: How many Americans under the age of, say, 30, have read The Great Gatsby? How many were taught it in their high school English classes? The book was assigned to neither of my Gen Z kids, and they went to different high schools. (Forgive me: This is when I assume the part of the old man thundering at the neighborhood kids to get off his lawn.) Novels, in general, seem to no longer be the backbone of the high school English curricula. And under the current administration, the Department of Education is set for demolition; in the not-too-distant future, our sophomores and juniors might be reading nothing but Trump-branded Bibles, hagiographies of Elon Musk, and The Art of the Deal. The novel—that surefire antidote to doomscrolling!—is going the way of opera, epic poetry, darkrooms, and vinyl.

And that’s why I have undertaken this quixotic project—what I hope will be the first in a series of classic literary works reissued by Four Sticks Press. Basically, I wanted an excuse to deep-dive into a book I love and write about what I found. And I was curious to know what my contemporaries thought of Gatsby, so I recruited two of my favorite writers, my friends Ronlyn Domingue and Diana Spechler, to contribute commentary. Their pieces are even more brilliant than I hoped they would be, and are alone worth the modest cover price.

Most of all, what I want is for people who’ve never read Gatsby to read it for the first time, and for people who read it a long time ago to revisit it. (And they’d better do it soon, before it gets banned.)

The goal of this centennial edition of Fitzgerald’s classic can be summed up in five words:

Make America Great Gatsby Again!

—G.M.O.

New Paltz, N.Y.

March 15, 2025

ICYMI

Kat Abughazaleh joins us, and Nadine Smith and Lisa Graves discuss their new show!

With the anticipated thousands [million+?] of heroic protestors on April 5th (actually any and all days, including Women's March) here's an updated partial list of those fighting back every day [as of 3-29-25). I'm also adding courageous law firms who haven't caved. Besides upstanding lawyers, and law-abiding honorable (present and former) judges (including James Boasberg, chief judge, D.C. District Ct.), here's a growing list of Profiles in Courage men, women, and advocacy groups who refuse to be cowed or kneel to the force of Trump/Musk/MAGA/Fox "News" intimidation:

I'll begin (again) with Missouri's own indomitable Jess[ica] (à la John Lewis's "get in good trouble") Piper/"The View from Rural Missouri," then, in no particular order, Heather Cox Richardson/"Letters from an American," Joyce Vance/"Civil Discourse," Bernie Sanders, AOC, Gov. Tim walz, Sarah Inama, Rev. Mariann Edgar Budde, Jasmine Crockett, Ruth Ben-Ghait, Rachel Maddow, Lawrence O'Donnell, Chris Hayes, Ali Velshi, Stephanie Miller, Gov. Janet Mills, Gov. Beshear, Gov. JB.Pritzker, Mayor Michelle Wu, J im Acosta, Jen Rubin And the Contrarians, Dan Rather, Robert Reich, Jay Kou, Steve Brodner, Rachel Cohen, Brian TylerCohen, Jessica Craven, Scott Dworkin, Brett Meiselas, Joy Reid, D. Earl Stevens, Melvin Gurai

Anne Applebaum, Lucian Truscott IV, Chris Murphy, Jeff Merkley, Elizabeth Warren, Tammy Duckworth,Sheldon Whitehouse, Adam Schiff, Jon Ossoff, Elyssa Slotkin, Tristan Snell, Delia Ramirez,Tim Snyder, Robert B. Hubbell, Ben Meiseilas, Rich wilson, Ron Filpkowski, Jeremy Seahill, Thom Hartmann, Jonathan Bernstein, Simon Rosenberg, Marianne Williamson, Mark Fiore, Jamie Raskin, Rebecca Solnit, Steve Schmidt, Josh Marshall, Paul Krugman, Andy Borowitz, Jeff Danziger, Ann Telnaes,͏ ͏Will Bunch, Jim Hightower, Dan Pfeifer, Dean Obeidallah, Liz Cheney, Adam Kimzinger, Cassidy Hutchinson--

American Bar Association, 23 blue state Attorney Generals, Indivisible. FiftyFifty one, MoveOn, DemCast, Blue Missouri, Third Act, Democracy Forward, Public Citizen, Democracy Index, Protect Democracy, DemocracyLabs, Fred Wellman/On Democracy, Hands Off, Marc Elias/Democracy Docket, Public Citizen, League of Women Voters, Lambda Legal, CREW, CODEPINK, ACLU, The 19th/Errin Haines, Working Families Party, American Oversight, Every State Blue, Run for Something, Jessica Valenti/Abortion Everyday, The American Manifesto

The Dr. Martin Luther King Center.

And, as Joyce Vance says, "We're in this together"--or via Jess Piper, from rural Missouri: "Solidarity." FIGHT BACK! WE ARE NOT ALONE! (Latest addition h/t , Robert B. Hubbell: Law firms, see below). All suggestions are welcome.

* Perkins Coie and Covington & Burling have resisted Trump, fighting back with the help of other courageous firms like Williams & Connolly. Per The ABA Journal,

Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr, representing fired inspectors general. (Law.com)

Hogan Lovells, seeking to block executive orders to end federal funding for gender-affirming medical care. (Law.com)

Jenner & Block, also seeking to block the orders on cuts to medical research funding. (Law.com, Reuters)

Ropes & Gray, also seeking to block cuts to medical research funding. (Law.com)

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, representing the Amica Center for Immigrants Rights and others seeking to block funding cuts for immigrant legal services. (Law.com)

Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer.

Wilmer Hale

Keker, Van Nest & Peters

Southern Poverty Law Center

Perhaps I should add our nation's motto--and on our Great Seal--the phrase "E pluribus unum" (out of many, One ). Ii's 13 letters makes its use symbolic of the original 13 Colonies which rebelled against the rule of the Kingdom of George III . . .And now we protest together against King Donald. As my rural MO. indomitable Jess Piper always says: "Solidarity"

Been a free subscriber for a while, just upgraded today after reading your great gatsby analysis. I’m 72 and just packing up the condo my husband and I just sold in Florida. I’m alone, because soon after we bought it, he got sick with some Gatsby like illnesses, so he is in a facility and I am picking up the detritus of a life of too much consumption. Certainly not rich, just 2 hardworking people who led a typical American life raising 3 good kids, and saving our money to….haven't figured that out yet. Hope to travel, because I haven’t done much in a too busy, too consumptive life as a working mother.

Of all the substacks I follow, I love your combination of political commentary, history, and literary knowledge. I have learned a lot from you, someone at least 20 years my junior. As fellow recovering Catholic and Jersey-raised, thank you for your hard work.