Dear Reader,

Two ships sailed into the harbor of the Dutch outpost of New Amsterdam in the summer of 1654: first the Peereboom, from Amsterdam, and a few weeks later the St. Catrina, from Recife. Aboard the latter were 23 Sephardic Jewish refugees fleeing persecution, as the liberal Dutch had just lost their colony in Brazil to intolerant Portugal. Aboard the former were “Jacob Barsimon, probably together with Asser Levy and Solomon Pietersen,” writes Leo Hershkowitz in the American Jewish Archives Journal. “These were the first known Jews to set foot in the Dutch settlement, and with them begins the history of that community in New York.”

Peter Stuyvesant, the governor of New Amsterdam, was not keen on the idea. There were already too many different religious groups in the city, he argued in a ranting letter to his employer, the Dutch West India Company; he did not wish Manhattan “invaded” by members of “the Jewish race.” And in what had to have been the first corporate DEI policy ever implemented in the New World, his bosses told him to STFU:

We observe that it would be unreasonable and unfair, especially because of the considerable loss sustained by the Jews in the taking of Brazil and also because of the large amount of capital, which they invested in shares of this Company. After many consultations we have decided and resolved upon a certain petition made by said Portuguese Jews, that they shall have permission to sail and trade in New Netherland and to live and remain there provided the poor among them shall not become a burden to the Company, or the community, but be supported by their own nation. You will govern yourself accordingly.

The sources disagree on which of the two ships carried her ancestors into what is now New York; what we do know is that the poet Emma Lazarus, born in 1849, is descended from the first Jewish families who landed there 37 decades ago. She was born in New York City, from families that were among the first residents of New York City. She made her reputation in New York City, died in New York City, and through her most famous poem, is inextricably tied to New York City. She is in every way a native New Yorker. But if there really is such a thing as ancestral trauma, as my friend Ronlyn Domingue talked about on the PREVAIL podcast recently—if memory is somehow handed down through our DNA—then Lazarus knew about religious persecution and exile and hatred. She was not a Daughter of the American Revolution, but a daughter of the Portuguese Inquisition.

In 1883, at the height of her fame and her poetical powers, Lazarus published two sonnets. Both are Petrarchan in structure—ABBA/ABBA/CDCD/CDCD. Both are about an arrival in the New World, and the emotions that arrival engenders. And yet they express such a vastly different perspective, it’s astonishing that the same poet produced both of them, let alone in the same year.

The lesser-known sonnet, “1492,” might have been written for the establishment of Indigenous Peoples Day in Berkeley, California, in 1992. More than a century earlier, Lazarus saw Christopher Columbus for the avaricious butcher he was:

1492

Thou two-faced year, Mother of Change and Fate,

Didst weep when Spain cast forth with flaming sword,

The children of the prophets of the Lord,

Prince, priest, and people, spurned by zealot hate.

Hounded from sea to sea, from state to state,

The West refused them, and the East abhorred.

No anchorage the known world could afford,

Close-locked was every port, barred every gate.

Then smiling, thou unveil’dst, O two-faced year,

A virgin world where doors of sunset part,

Saying, “Ho, all who weary, enter here!

There falls each ancient barrier that the art

Of race or creed or rank devised, to rear

Grim bulwarked hatred between heart and heart!”

In other words, the conquistadors came to the New World because no one else would have them, and they murdered and pillaged, and they established a country based on hatred and zealotry and greed. Eat your heart out, Howard Zinn!

Contrast this to her poem with which everyone is familiar, inscribed as it is at the base of the Statue of Liberty. “The New Colossus,” too, is a Petrarchan sonnet. The old Colossus alluded to in the title and the first few lines is the one at Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, destroyed by an earthquake. According to contemporary sources, it looked like this:

…which is to say, like a big, strapping dude about to tinkle into the harbor. It suggested manly power, if not outright menace. The Bartholdi statue in New York communicated something entirely different, which Lazarus expresses beautifully in her sonnet:

The New Colossus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

This is stirring, powerful stuff. How many times have we read the last five lines of that poem? And yet with each reading, I am no less moved. Lazarus donated the poem to the fund to raise money for the statue’s pedestal, and my goodness did she understand the assignment!

As it often does, the U.S. government was sending mixed messages. The Statue of Liberty—Mother of Exiles!—was dedicated in 1883, a year after Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act and an Immigration Act banning entry for aliens who were convicts, “lunatics,” and those “likely to become a public charge”—two bills a 19th century Donald Trump would have enthusiastically supported. Lazarus must have been aware of the irony.

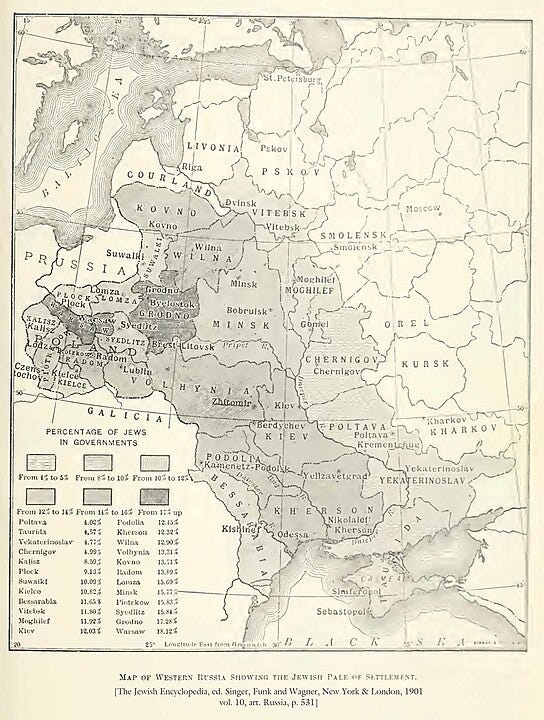

In 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. The Romanov government, already oppressive, began to really crack down. Russian Jews bore the brunt of this. Already prohibited from living outside the designated Western region of Russia called the Pale of Settlement, Jews were now subject to pogroms; they were brutalized, their homes and businesses destroyed. A series of “May laws” enacted by the odious Alexander III further limited their movement around Russia and their ability to run businesses. (Ethnic cleansing by the Russian government, alas, is nothing new). This began the wave of Eastern European Jewish immigration to New York. Between 1881 and 1910, some 1.5 million Jews, most from Russia, came to the United States. Ellis Island, which opened in 1892, welcomed them with open arms, thanks in part to the empathy shown by Colonel John B. Weber, President Harrison’s immigration commissioner, who toured Eastern Europe and was horrified by their treatment there.

Later in her too-short life—she died in 1887, somehow just 38 years old; her first collection of poetry was published when she was still a teenager—Lazarus became fascinated by her Jewish heritage. She wrote extensively, both in poetry and prose, about her faith, and often contemplated the plight of the exile. (Relatedly, she was an early proponent of what was later called Zionism). And she lent her considerable energies to helping the immigrant Jews coming from Russia to New York. She was a founder of the Hebrew Technical Institute and the Society for the Improvement and Colonization of East European Jews, and a volunteer with the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society. Emma Lazarus was not some one-hit wonder. She was a poetical genius, a master of her art form, a prolific writer, a tireless activist, a formidable figure, a great American.

After the Great War, American attitudes toward immigration changed. There was always a tug of war between nativists and immigrants. With the passage of the Barred Zone Act of 1917, nativism won the day. Literacy became a prerequisite for immigration, and most residents of Asia and the Pacific were barred entry. It was at this time that the first tests of “intelligence” were developed, by Robert Yerkes and Walter Bingham; they were egregiously racist, patently unfair, and, unfortunately, extremely influential in Washington. Poles, being the most recent immigrant group to arrive in the U.S., were found by these eugenicist data scientists to be the least intelligent ethnic group; this is the origin of “Polack” jokes. (The Harvard scientist Stephen Jay Gould wrote an amazing book about this, The Mismeasure of Man).

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 effectively slammed the door on immigration, even from Europe, establishing quotas based on race, ethnicity, and nationality. This garbage piece of legislation, influenced by the work of Yerkes and Bingham, had a profound effect on world events. It was because of the quotas in the Johnson-Reed Act that boatloads of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany, most famously the St. Louis, were denied entrance to the United States—a death sentence for many of them, who would perish in the Holocaust. FDR did not intervene, fearing that some of the Jews on the ships were German spies.

Consider this: The American government run by the Dutch West India Company let in Jewish refugees fleeing from extermination; the American government run by Franklin Delano Roosevelt turned them away. What would Emma Lazarus have thought of that?

Bartholdi’s giant sculpture is often shown as the personification of the United States. But it is not the Statue of America; it is the Statue of Liberty, and despite our lofty words and grand pretenses, those two things have seldom gone hand in hand on these shores. Taken together, the two Lazarus sonnets remind us of both the pettiness and horror that marked the colonization of the continent and the promise and hope for a better future for one and all.

The statue is the Mother of Exiles, and all of us Americans—even the displaced Indigenous People—are descended from exiles, if we go back far enough. We were all tired and poor, once upon a time. Freedom—liberty, if you will—comes and goes, historically. We have lost freedoms in this country over the last few years, and if Trump prevails next November, we will lose a lot more. But the yearning for freedom cannot be lost. It is everlasting, unchanging. No tyrant can extinguish that flame. Like the poet’s namesake, it never dies.

ICYMI

We did a “neat” Five 8 on Friday, sans guest:

Finally: I’m sorry to report that David Benjamin—kick-ass OSINT researcher, engaged member of the community, and good dude—recently suffered a stroke and is unable to work. His brother has organized a (very modest) GoFundMe to help him pay for basic expenses at this time. I wish him a speedy recovery.

Photo credit: Arpan Parikh via Pexels.

"like a big, strapping dude about to tinkle into the harbor"🤣

That was my lol moment reading this well written, interesting essay. Bravo. How do you know so much, man?

Speedy recovery to your friend.

Thank you for another remarkable history lesson! I am so thankful Canadian immigration laws of the past allowed ‘criminals’ to come to Canada. Years ago, my brother did some digging into our family’s past and found that our father’s ancestor had a choice to stay in a French prison or come to Canada. Our family is proud of our French heritage and happy to say, we are law abiding Canadian citizens!