Dear Reader,

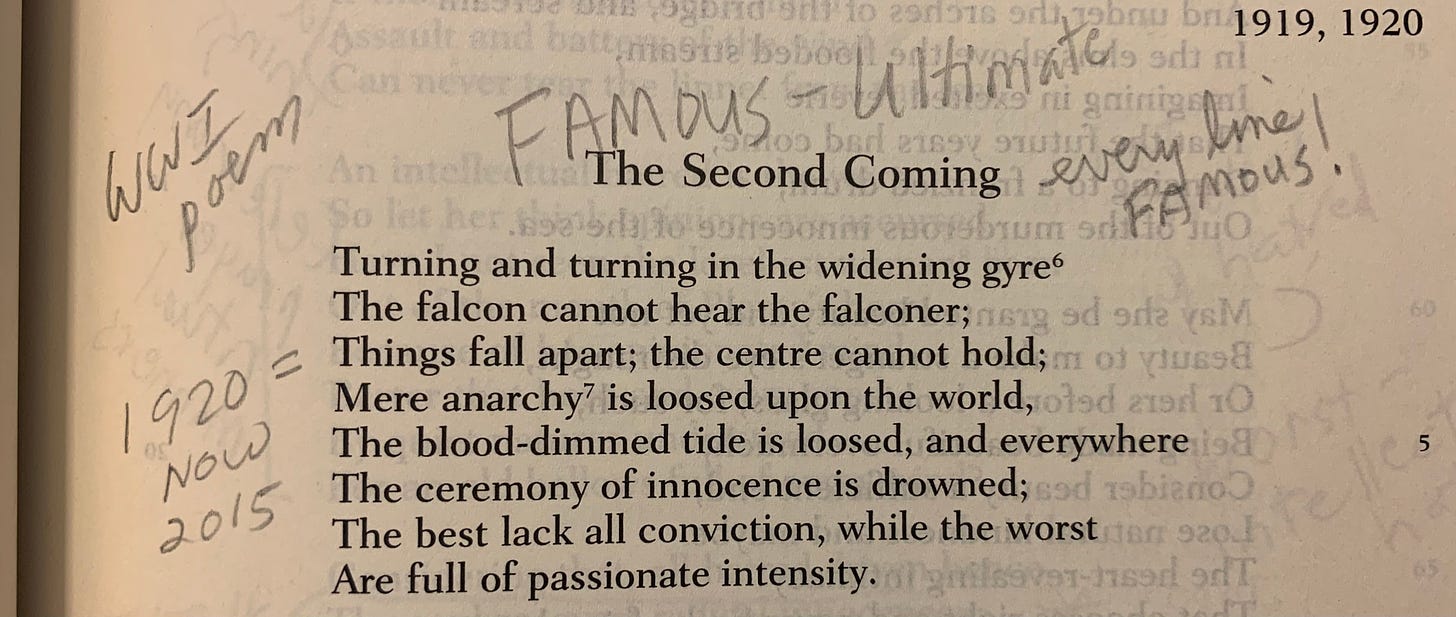

At the book fair last year, I scored a lovely copy of Volume 1 of the Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry. Not only is this a delightful volume, but it contains handwritten annotations by some meticulous poetry student who took dutiful notes in the margins. What reader of verse cannot be charmed by this:

What the anonymous annotator jots down here is correct; every line is FAMOUS.

I’ve written previously about “The Second Coming,” the “famous-ultimate” poem William Butler Years wrote after the Great War, back in September of 2021—the early days of the Biden-Harris administration and the latter days of the pandemic. “Has the world gone mad?” I asked at the opening of the piece. But 19 months later, the examples of madness cited then seem quaint next to what’s been happening since. Too, the poem is so good, and so of the moment, that I wanted another crack at it.

It begins:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

It is the falcon who is “turning and turning,” high in the sky, making a pattern associated with hypnosis. As for the gyre—which Yeats pronounced, I’m told, with a hard “g,” as in guest—that’s a fancy word for circular motion, with the same root as gyrate. But to the poet, gyre had a specific connotation. Yeats explained in his notes on the poem that “the end of an age, which always receives the revelation of the character of the next age, is represented by the coming of one gyre to its place of greatest expansion and of the other to that of its greatest contraction.” If we peel away the mumbo-jumbo, we see that Yeats is talking about the proverbial pendulum swinging in the opposite direction.

He is right about the Great War heralding the end of an age. “The Long Nineteenth Century,” a phrase coined by the great historian Eric Hobsbawm, is the period beginning with the French Revolution and ending with the onset of the First World War. So: the death of the king through the death of the archduke. Hobsbawm chose 1991 as the final year of the era that followed, which he calls the “Age of Extremes:” from the Great War through the collapse of the Soviet Union. I wrote about the outsized significance of that year in my first novel, Totally Killer. But now I’m not so sure I agree with him about the second parenthesis. What came after the Great War—what was novel—was fascism, dictatorship, totalitarianism. Not the Age of Extremes but the Age of Strongmen. And we are still, regrettably, living in that era, it seems to me.

The “extremes” are not those between capitalism and communism—the latter has existed in name only—but between democracy and tyranny. In Yeats’ framework, one expands while the other contracts. What exists in the middle, the “centre,” is not powerful enough to stem the centrifugal forces. Figuratively speaking, the moderates are drawn and quartered.

Back to the poem:

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

Yeats is probably thinking about losses on the battlefield here, but in 2023 America, the drowning of innocents in blood refers to the spate of mass shootings, especially in our schools, as well as the women denied access to healthcare who will now suffer and die more frequently during pregnancy and in childbirth.

Anarchy in this sense is not the political movement, which in Yeats’ time was the engine of progressivism, but literal anarchy, no ruler to speak of, no laws, or laws that make no sense at all: the deranged shit the mad scientists are cooking up right now in that fascist laboratory known as Florida.

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

This needs no explanation. Marjorie Taylor Greene is passionately intense, as is Sam Alito, Leonard Leo, Steve Bannon, Mike Flynn, and so on down the line. The rest of us, traumatized, disappointed time and again by those who should be our protectors, our champions, have become tentative, if not completely hollow inside.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight:

The Second Coming: the preposterous belief that we will be saved by some invisible, external, supernatural force because of a prophesy scrawled in a book two thousand years ago. Or that we will be saved by Jim Comey, or Robert Mueller, or Christopher Wray, or Merrick Garland, or Jack Smith, or anyone other than ourselves. I cannot speak to what happens after we die. But here on earth, we are our own salvation.

The Latin phrase Spiritus Mundi, meaning “spirit of the universe,” is the collective unconscious—what Yeats called “a general storehouse of images.” And this harrowing image, drawn perhaps from the Revelation of John of Patmos, is what his mind conjures up (rather like Ray in Ghostbusters imagining Gozer the Destroyer returning as the Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man):

somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

Birds again, like the falcon at the opening of the poem. Birds know, don’t they, which way the wind blows. They are the true prophets.

The poem concludes:

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

There are, alas, rough beasts slouching all around us, in positions of vast power. Donald John Trump is a rough beast. So is Ron DeSantis, and Clarence Thomas, and Brett Kavanaugh, and Steve Bannon, and Alex Jones. But their ubiquity is not unique to this moment. There were rough beasts in Yeats’s day, too. History is littered with the carcasses of rough beasts.

Happily, the gyre does not widen forever. Yeats sees the system as cyclical, not entropic. It’s been over a century since Sarajevo and since “The Second Coming” was written. One way or another, the Age of Strongmen is drawing to a close. Unlike kings, dictators die leaving no presumptive heirs.

Implicit in the Yeats poem is this message: The center will re-form. Our conviction will be rekindled. The falcon will return. The real question is, what will come next?

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Alex Aronson, former chief counsel to Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse. This is an important discussion on the Supreme Court:

ETC.

The folks at Palladium Magazine made this short film about the brilliant Sandy Lewis that I found fascinating:

Photo credit: Yours Truly.

Good morning, love how you reach back for examples with an eye towards the future. When I find myself in times of trouble (like every other day or so), my lodestar is the pendulum. Makes the most sense to me that it always has to swing back to neutral, but I can't help but worry this swing was much wider, and find it even harder to avoid thinking violence is necessary to counter the madness. Too many rough beasts out there that need the shit kicked out of them to worry about getting my hands dirty or breaking a nail. Bring it

Like you, Joni Mitchell also did this poem proud.