Dear Reader,

“You are all a lost generation,” said Gertrude Stein to Ernest Hemingway, probably with an exasperated shake of her head, in Paris in the years after the Great War.

The word lost conveys any number of meanings in that famous quip, few of them happy. Talk about being born at the wrong time! These were the men and women who came of age during the war, who fought in the war and died or were wounded, and who came home to a United States where alcohol was illegal.

But in my formative years, lost roughly translated to cool. The fiction writers of the Lost Generation, in my young mind, were the best the country had to offer. And my impression, as an adolescent with literary ambitions, was that the three greatest American writers of that doomed cohort were F. Scott Fitzgerald (b. 1896), William Faulkner (b. 1897), and Ernest Hemingway (b. 1899). That power trio was who to emulate—or, at least, that was my sense, as a (straight white male American) teenager.

We read The Great Gatsby in class, of course; that was and remains the Great American Novel. We read The Sound and the Fury, which was over my head. But by the time I got to high school in 1987, Ernest Hemingway had fallen out of fashion, expunged from the curriculum. (“Cancelled!” Josh Hawley might say.) I remember being surprised at this. Wasn’t Hemingway one of the Big Three?

This was the period where there was a concerted effort to expand the canon by assigning books that were not all by dead white guys—a noble and necessary adjustment, and one I benefited from—and it made sense to bail on Hemingway. He was a DWAM, not a DWEM, but at least on the surface, his work pulsated with straight white masculinity. Should 15-year-olds really be taught novels about bullfights and safaris and drunken benders in Interwar Paris? His best-known short story is about a guy trying to convince his pregnant girlfriend to have an abortion. I could see teachers potentially getting some heat for assigning that.

Is Hemingway taught much nowadays? Certainly my kids aren’t reading him in school. And that’s a shame. Because, contrary to popular opinion, Ernest Hemingway is not the Joe Rogan of letters. He’s not Red Pill Lit. He was an extraordinarily sensitive human, and that is reflected in his work. Death in the Afternoon, for example, is a book about bullfighting, but it hardly excuses the brutality of that sport. Throughout, you get the sense that Hemingway is struggling with having passion for something that contains such violence and cruelty, that he’s trying to give voice to all of it, the ugly and the sublime. I’d argue that he writes about masculinity in the same way: on some level, traditional masculinity makes him uncomfortable, and that’s why he explores it.

Hemingway came up as a journalist, and that sensibility never left him. He was an open-minded and curious guy who went out on wild adventures, and then wrote about his experiences. He was a larger-than-life presence, always in the thick of things. And he was funny; it was Hemingway who supplied the rejoinder to Fitzgerald’s comment about the rich being different than us: “Yes, they have more money.”

Despite being an alcoholic who suffered enough from depression that he wound up committing suicide, he was disciplined. Whether he was in a Paris flat or his house on Key West, he wrote dutifully every morning, in a simple, no-bullshit style that is as distinctive and recognizable as any writer’s voice has ever been. No one else wrote quite like Ernest Hemingway.

Hemingway’s work has been accused of being sexist. And there is merit to these arguments, for sure. Obviously, a man born in the last year of the 19th century is going to have different prejudices and biases about gender roles than someone in high school now. But is he really worse than his contemporaries? Fitzgerald gave us that horrible caricature, Daisy Buchanan, who I once described as “one of the biggest pieces of shit in all literature.” I tried reading some Faulkner novels recently, and had to stop because the misogyny was so pervasive and off-putting. Hemingway’s work, by contrast, teems with strong, interesting, three-dimensional women, and the men, the macho ones especially, are always deeply, deeply flawed. This is on full display in my favorite of his books, The Sun Also Rises.

I first read The Sun Also Rises in high school—we were allowed to pick a novel for an independent study project, and I wanted to see what the fuss was all about. (Also, my parents had a copy, and it was short.) At age 16, I could follow the action well enough, but I missed most of the nuance. I understood that Brett Ashley, the love interest of narrator Jakes Barnes, is immensely desirable—not because of how she looks (“she looked very lovely” is how Hemingway describes her when she first appears), but because of how she acts. She’s smart, cool, fun, capable (she was a nurse in the war), impulsive, reckless, and, like Barnes, damaged from her participation in the war.

At age 16, I did not fully understand the nature of Barnes’s injury, and how it was a permanent obstacle to the two lovers living happily ever after. Here is how it is revealed in the book—Jake in his flat after a night out of heavy drinking:

Undressing, I looked at myself in the mirror of the big armoire beside the bed. That was a particularly French way to furnish a room. Practical, too, I suppose. Of all the ways to be wounded. I supposed it was funny. . . .

My head started to work. The old grievance. Well, it was a rotten way to be wounded and flying on a joke front like the Italian. In the Italian hospital we were going to form a society. It had a funny name in Italian. . . . [T]he liaison colonel came to visit me. That was funny. That was about the first funny thing. I was all bandaged up. But they had told him about it. Then he made that wonderful speech: “You, a foreigner, an Englishman” (any foreigner was an Englishman) “have given more than your life.” What a speech! I would like to have it illuminated to hang in my office. He never laughed. He was putting himself in my place, I guess. “Che mala fortuna! Che mala fortuna!”

Ironic, isn’t it, that the writer known for being uber-masculine wrote an entire novel about a guy who had his junk blown off!

Not long after this unfortunate incident, we learn, Jake met Brett, who was his nurse. They fell in love, a doomed love. “I suppose she only wanted what she couldn’t have,” Barnes reflects as he tries to sleep. Later that same night, a drunk Brett comes to see Jake, waking up everyone in his building, and they drive around and make out a little, but it goes nowhere; both of them recognize the futility. After she leaves, he goes back to bed and is miserable: “It is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime, but at night it is another thing.”

The Jake-Brett relationship is extreme, of course, but it strikes me as realistic. How many ill-paired, ill-starred couples try and try again, knowing full well it will never work out, because of habit, or hope, or false optimism? He cares for her as best as he can, but he cannot give her everything she requires, even though they both wish that this were not the case. Furthermore, they have the luxury of pretending that if Jake were intact, they would be together, and happy—which, given their various flaws, is almost certainly not how things would have played out.

That’s what makes the end of the book so achingly powerful:

“Let’s get two bottles," I said. The bottles came. I poured a little in my glass, then a glass for Brett, then filled my glass. We touched glasses.

“Bung-o!” Brett said. I drank my glass and poured out another. Brett put her hand on my arm.

“Don’t get drunk, Jake,” she said. “You don't have to.”

“How do you know?”

“Don’t,” she said. “You'll be all right.”

“I’m not getting drunk,” I said. “I’m just drinking a little wine. I like to drink wine.”

“Don’t get drunk,” she said. “Jake, don’t get drunk.”

“Want to go for a ride?” I said. “Want to ride through the town?”

“Right,” Brett said. “I haven't seen Madrid. I should see Madrid.”

“I’ll finish this,” I said.

Down-stairs we came out through the first-floor dining-room to the street. A waiter went for a taxi. It was hot and bright. Up the street was a little square with trees and grass where there were taxis parked. A taxi came up the street, the waiter hanging out at the side. I tipped him and told the driver where to drive, and got in beside Brett. The driver started up the street. I settled back. Brett moved close to me. We sat close against each other. I put my arm around her and she rested against me comfortably. It was very hot and bright, and the houses looked sharply white. We turned out onto the Gran Via.

“Oh, Jake,” Brett said, “we could have had such a damned good time together.”

Ahead was a mounted policeman in khaki directing traffic. He raised his baton. The car slowed suddenly pressing Brett against me.

“Yes,” I said. “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

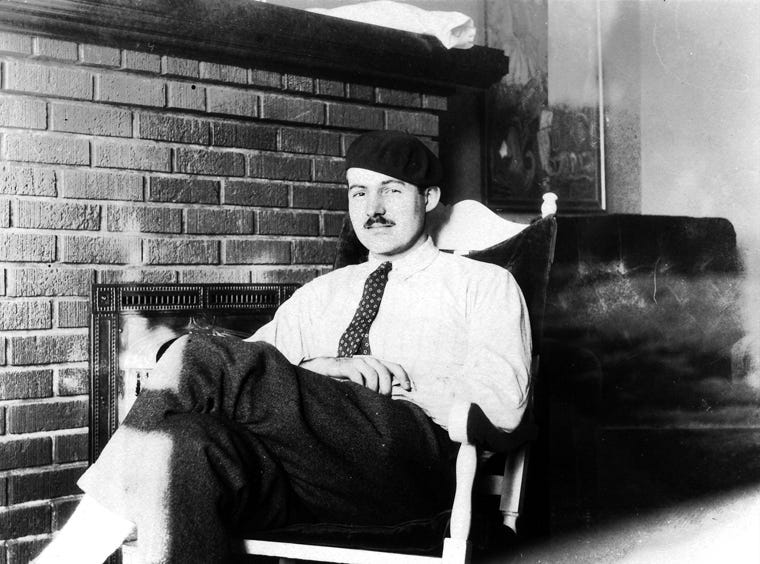

Photo credit: Ernest Hemingway, Paris, circa 1924. Photograph in the Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston. From Eleanor Jaekel.

Hemingway is underrated, regardless of what is said about him. Writing, for him, was like a boxing match, every sentence a punch, and he was the greatest at it. Thanks for reminding me. I think I love your columns on literature more than the ones on politics, although the eternal verities are clear in both.

When I shared this on my FB page today (you are well known to my friends, btw), I did so with a warning NOT to read it if anyone has the slightest feelings of depression today. That's how Hemingway always washed over me. As John Yearwood wrote below, there's a "punch" in his style and if one is very sensitive or emotional, that punch can feel like a knockout!