Dear Reader,

I made two trips to the Elting Library Book Fair last weekend, bringing home three shopping bags full of hard-bound and paperback booty. (Total cost: $58.) Among all the inviting volumes in my newly-acquired plunder, the one that called out to me was a short book by the French essayist Julien Benda, La Trahison des Clercs—which in Richard Aldington’s English translation is rendered The Treason of the Intellectuals.

Treason being a chief interest of mine ever since Donald Sr. came down the gilded escalator in 2015, and Frenchmen having a reputation for savvy takes on the goings-on in the United States since Alexis de Tocqueville, I was eager to see what Benda had to say. So last Sunday, as the Jets played the most boring game of professional football since the advent of the forward pass, I sat on the couch and read the whole thing, cover to cover.

Immediately, I was taken by how accurately Benda describes the situation on the ground in the U.S. Two years ago, Joe Biden called the 2020 midterm elections “a battle for the soul of the nation.” “Donald Trump and the MAGA Republicans represent an extremism that threatens the very foundations of our republic,” the President said, quite correctly.

Taking this a step further, Benda is able to isolate the essential characteristic of Trump and the New Right thought leaders, such as they are: the elevation of heartlessness and the rejection of compassion—what he calls “the extolling of harshness and the scorn for human love, pity, charity, benevolence.” What is MAGA, distilled to its raw form, if not that?

I found myself nodding in vigorous agreement as I read on:

They are not content to remind the world that harshness is necessary in order to succeed and that charity is an encumbrance; nor have they limited themselves to preaching to their nation or party what Zarathustra preached to his disciples: “Be hard, be pitiless, and in this way dominate.” They proclaim the moral nobility of harshness and the ignominy of charity…

It is a commonplace that among the great majority of the (so-called) thinking young men…harshness is today an object of respect, while human love in all its forms is considered a rather laughable thing. These young men have a cult for doctrines which respect nothing but force, pay no attention to the lamentations of suffering, and proclaim the inevitability of war and slavery, while they despise those who are revolted by such prospects and desire to alter them.… [They] have created in so-called cultivated society a positive Romanticism of harshness.

…These people have come to see that by feeling contempt for others they are not only obtaining the pleasure of a lofty attitude, but that when they are really expert in expressing contempt they harm what they despise, do it a real damage…

It may also be said that they have created a cult for cruelty.

Trump is the exemplar of Harshness and Cruelty (a pair of words that sounds more like a grounding Nietzschean philosophy when rendered in German: Härte und Grausamkeit). Whether he is yanking out his wife’s hair, smacking his namesake son, screwing over vendors who demolished the Bonwit Teller building, insulting John McCain or wounded veterans or the fallen at the CIA’s Wall of Stars, denying his infirm nephew medical coverage, hurling paper towels at hurricane victims, calling for the executions of innocent Black men, fantasizing about cops roughing up immigrants, or making jokes at the expense of the MAGA fireman who died at the first rally in Butler, PA, Donald Sr. is animated by harshness and cruelty. He gets off on it. It nourishes him.

But it’s not just Trump. We also see Härte und Grausamkeit in JD Vance, in Elon Musk, in Peter Thiel and the libertarian tech bros, in Sam Alito and the radical Catholic weirdos on the Supreme Court, in Greg Abbott and Dan Patrick and Ken Paxton in Texas, in the Proud Boys and other white nationalist groups, in Charlie Kirk and Chaya Raichik and other hateful rightwing media figures, and many more besides. These are people who delight in the suffering of others, who make a living indulging in that delight, and who would therefore rather cause suffering than alleviate it. MAGA is hatred, and hatred is MAGA.

As Benda astutely observes in the book, “They know that the maintenance of these hatreds will cost the lives of their children”—one thinks here of the children gunned down in mass school shootings, as Vance rails against doors and windows—“but they do not hesitate to make the sacrifice, if by doing so they retain possession of their property and their power over their servants. Here is a grandeur of egotism which is perhaps insufficiently appreciated.”

But what’s really remarkable about The Treason of the Intellectuals is that it was published in 1927.

Benda started writing it a hundred years ago.

Julien Benda was a man of letters, an ardent Dreyfusard whose worldview was formed during the Dreyfus affair and the debates that raged in France after Emile Zola published his famous “J’accuse!” letter in 1898. He was of the class of intellectuals he accused of betrayal. As Adam Kirsch wrote in 2020 in the Jewish Review of Books:

The term “intellectual” entered the debate when L’Aurore, the newspaper where Zola’s letter appeared, published a statement of support written by its editor, Georges Clemenceau, who would later lead France to victory as prime minister during World War I. It was signed by many prominent cultural figures, described by Clemenceau as “all these intellectuals, from every point on the horizon, who join together under one idea.”

As a coherent argument, I found Benda’s book fascinating but ultimately unconvincing. His thesis is that there is a class of intellectuals—writers, poets, priests, painters, philosophers and the like—who, traditionally, steered clear of terrestrial matters. Only when that collective group became involved primarily in politics, he argues, did things really go south. He was a secularist, but his book seems to call for more spirituality and/or religion in public life. As Kirsch notes in his essay, “It would be easy to read Treason without realizing that it is a book by a Jewish writer attacking notorious Jew-haters and that the Jewish question had been bound up with the very issues Benda was writing about since the Dreyfus affair….Not only did Benda not write as a Jew, he seemed to write as a Christian,” and I agree with Kirsch. There is a Catholic undertone to the work that reminded me a little of Bill Barr’s speech at Notre Dame.

But isolate individual passages from Treason, and oh my goodness. Like, this passage—again, from 1927!—is remarkably, uncomfortably prescient:

I shall point out another great increase of power in national sentiment which has occurred in the last half-century. I mean that several very powerful political passions, which were originally independent of nationalist feeling, have now become incorporated with it. These passions are: a) the movement against the Jews; b) the movement of the possessing classes against the proletariat; c) the movement of the champions of authority against the democrats. Today each one of these passions is identified with national feeling and declares that its adversary implies the negation of nationalism. I may add that when a person is affected by one of these passions he is generally affected by all three; consequently nationalist passion is usually swelled by the addition of all three. Moreover this increase is reciprocal, and it may be that said that today capitalism, antisemitism, and the party of authority have all received new strength from their union with nationalism. . . .

Our age is indeed the age of the intellectual organization of political hatreds. It will be one of its chief claims to notice in the moral history of humanity.

To summarize: today political passions show a degree of universality, of coherence, of homogeneousness, of precision, of continuity, of preponderance, in relation to other passions, unknown until our times. They have become conscious of themselves to an extent never seen before. Some of them, hitherto scarcely avowed, have awakened to consciousness and have joined the old passions. Others have become more purely passionate than ever, possess men’s hearts in moral regions they never before reached, and have acquired a mystic character which had disappeared for centuries. All are furnished with an apparatus of ideology whereby, in the name of science, they proclaim the supreme value of their action and its historical necessity. On the surface and in the depths, in spatial values and in inner strength, political passions have today reached a point of perfection never before known in history. The present age is essentially the age of politics.

Mais oui! Not long ago, there were sanctuaries where one could enjoy life without one’s mind coming back to politics—specifically, the awful, hateful politics of MAGA. Trump mapped out these oases and conquered them. How can I watch football without thinking of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee, or Aaron Rodgers being a conspiracy-mongering kook who was rumored to be on the short list of running mates for RFK, Jr, or the Bosa brothers being MAGA, or Patriots owner Robert Kraft giving one of his Super Bowl rings to Vladimir Putin, or how Travis Kelce’s girlfriend’s endorsement of Kamala Harris might affect the cohesion of the Chiefs’ locker room? Trump supporters wear their crass, disrespectful, and overtly political t-shirts and hats everywhere: at airports, at coin shows, at sporting events, at pizzerias. We can’t ignore this thing. They won’t allow it. Like the spray of a particularly noxious skunk, its stink can be smelt from the mountains to the prairies to the oceans white with foam. America is redolent with the fetid MAGA reek.

In Treason—famously, although I had never heard of this book or its author until a week ago—Benda predicted WW2:

Indeed if we ask ourselves what will happen to a humanity where every group is striving more eagerly than ever to feel conscious of its own particular interests, and makes its moralists tell it that it is sublime to the extent that it knows no law but this interest—a child can give the answer. This humanity is heading for the greatest and most perfect war ever seen in the world, whether it is a war of nations, or a war of classes.

Even his phrasing—the greatest, the most perfect ever seen—is eerily Trumpy.

Benda is not a pacifist per se; he understands the occasional necessity of war, like it or not. There is a part in the book where he rails against “mystic pacifism,” which he calls “the pacifism which is solely animated by a blind hatred of war and refuses to inquire whether a war is just or not, whether those fighting or the attackers or the defenders, whether they wanted war or only submit to it.” That sounds, to me, like language used by the Putin fluffers in Congress and elsewhere, urging peace in Ukraine without acknowledging that a ceasefire there awards the occupiers and not the occupied.

But he also understands how the elimination of war requires a moral leveling up. “Mussolini proclaims the morality of his politics of force and the immorality of everything which opposes it,” Benda notes. How to overcome such a puissant dividing force?

Peace, it must be repeated after so many others have said this, is only possible if men cease to place their happiness in the possession of things “which cannot be shared,” and if they raised themselves to a point where they adopt an abstract principle superior to their egotism. In other words, it can only be obtained by a betterment of human morality.

But this is what really blew me away. Yes, he foresaw the Second World War. But he also conceived of a different possibility for the future—a third way. In a world bound together so tightly by social media, by the global economy, by a wondrous technology unthinkable to someone a century ago, even a brilliant intellectual like Julien Benda, we seem to be zooming along (or Zooming along?) a superhighway to that third science-fiction-y outcome.

This is how Benda ends his book. And the last line, I should add, is ironical, and therefore hits hard:

I said above that the logical end of the “integral realism” professed by humanity today is the organized slaughter of nations or classes. It is possible to conceive of a third [outcome], which would be their [the nations and classes] reconciliation. The thing to possess would be the whole earth, and they would finally come to realize that the only way to exploit it properly is by union, while the desire to set themselves up as distinct from others would be transferred from the nation to the species, arrogantly drawn up against everything which is not itself. And, as a matter of fact, such a movement does exist. Above classes and nations there does exist a desire of this species to become the master of things, and, when a human being flies from one end to the of the world to the other in a few hours, the whole human race quivers with pride and adores itself as distinct from all the rest of creation. At bottom, this imperialism of the species is preached by all the great directors of the modern conscience. It is Man, and not the nation or the class, whom Nietzsche, Sorel, Bergson extol in his genius for making himself master of the world. It is humanity, and not any one section of it, whom Auguste Comte exhorts to plunge into consciousness of itself and to make itself the object of its adoration. Sometimes one may feel that such an impulse will grow ever stronger, and that in this way inter-human wars will come to an end. In this way humanity would attain “universal fraternity.” But, far from being the abolition of the national spirit with its appetites and its arrogance, this would simply be its supreme form, the nation being called Man and the enemy God. Thereafter, humanity would be unified in one immense army, one immense factory, would be aware only of heroisms, disciplines, inventions, would denounce all free and disinterested activity, would long cease to situate the good outside the real world, would have no God but itself and its desires, and would achieve great things; by which I mean that it would attain to a really grandiose control over the matter surrounding it, to a really joyous consciousness of its power and its grandeur. And History will smile to think that this is the species for which Socrates and Jesus Christ died.

This future is Orwell mixed with Huxley; it is the triumph of Härte und Grausamkeit.

What Benda means here, I think, is an end of the need for conventional warfare—not because of our moral evolution, but because humankind will have lost the spiritual, the holy, war. Or, as our outgoing President might put it, the battle for the soul of humanity.

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Ernest Owens. Really interesting discussion on the VP debate, the Jack Smith filing, MAGA and masculinity, and much more:

Don’t forget: the Five 8 live event is happening in NYC on November 10th!

This is an incredible piece Greg and I thank you for always teaching me something new. It's a conundrum for sure...I mean I just do not understand the Maga cult at all. I gave up trying, packed up the family, escaped Texas (the absolute gutter politically) and relocated to New Mexico. Life has become real again! All the very best to you and your family.

Whenever I think of MAGA:

‘Individuals are not bad, crowds are simply mad – because, in a crowd, nobody feels responsible. You can commit murders in a crowd easily, because you know the crowd is doing it and you are just a wave in it, you are not the deciding factor, so you are not responsible. Individual, alone, you feel a responsibility. You will feel guilty if you commit something. It is my observation that sin exists through crowds, no individual is ever a sinner. And individuals, even if they commit something wrong, can be taken out of it very easily; but crowds are impossible, because crowds have no souls no centers. To whom to appeal? And in all that goes on in the world – the devil, the evil forces – the crowd is in fact responsible. Nations are the devil; religious communities are the evil forces. Belief makes you a part of a bigger crowd than you, and there is a feeling of elation when you are a part of something bigger, a nation – India, or America, or England. Then you are not a tiny human being. A great energy comes to you and you feel elated. A euphoria is felt. That’s why, whenever a country is at war, people feel very euphoric, ecstatic. Suddenly their life has a meaning – they exist for the country, for the religion, for the civilization; now they have a certain goal to be achieved, and a certain treasure to be protected. Now they are no longer ordinary people, they have a great mission.’

But also…I like to think we, the people, have now felt a ‘euphoria’, a euphoria of joy, not the ‘dark maga’ group-think we are up against.

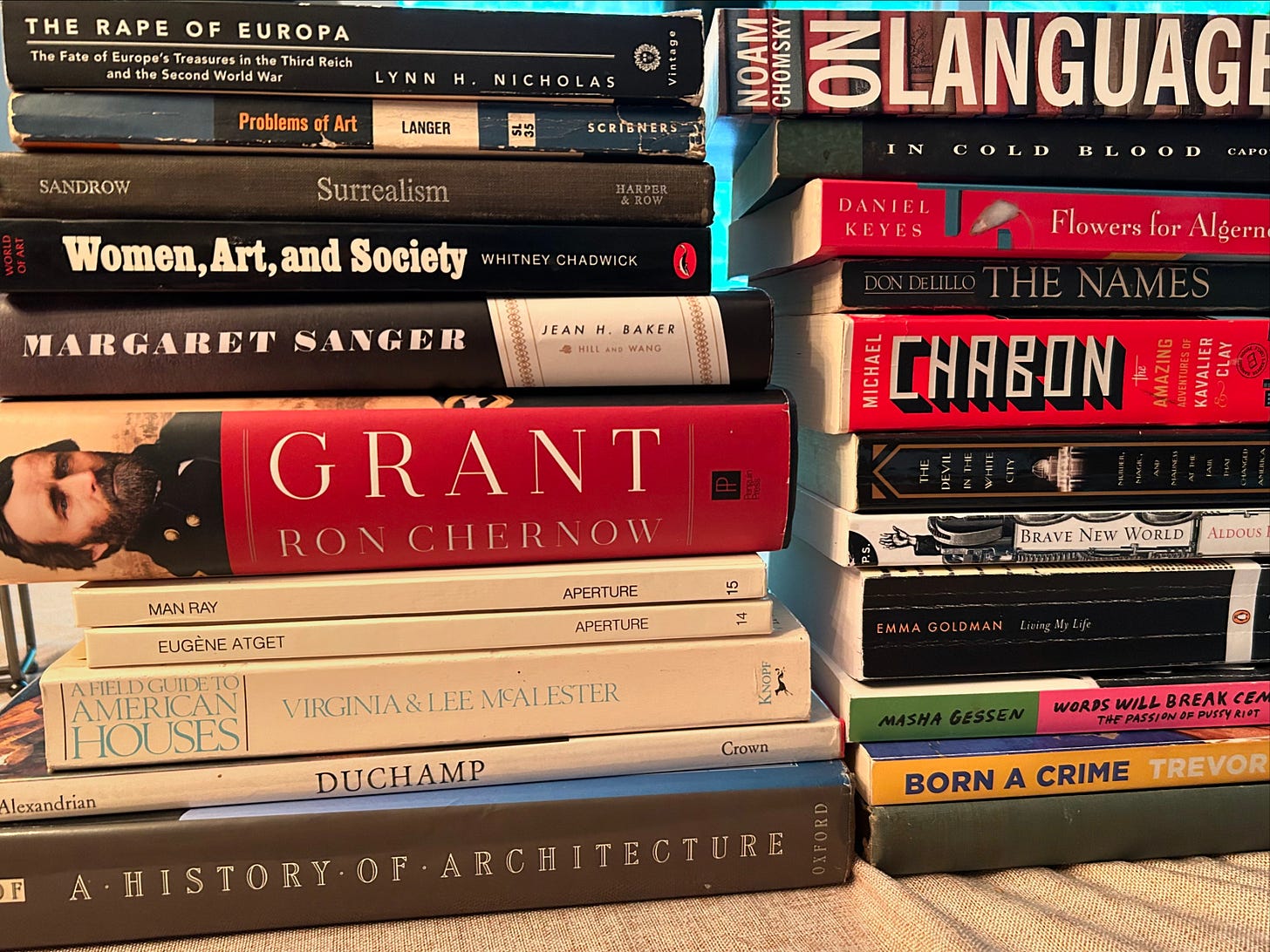

Thank you for sharing. Each time I read a column here, my reading list grows exponentially 😁