Dear Reader,

In Paris between the wars, Gertrude Stein, then in her fifties, said to Ernest Hemingway, who was half her age at the time, “You are all a lost generation.” He used Stein’s astute, poetical observation—which she appropriated from her auto mechanic—as the epigram for The Sun Also Rises. Thus an offhand remark at some lost soiree at 27 rue de Fleurus entered the popular culture and became the moniker for Hemingway’s entire beautiful and damned cohort: the generation of unfortunate souls that came of age during the Great War. The number of prominent poets and writers in that group is dizzying: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Eliot, Joyce, Huxley, Woolf, Millay, Steinbeck, Henry Miller. Literature leveled up during their heyday.

I read The Sun Also Rises in high school—on my own accord, as Hemingway had been eighty-sixed from the literary canon by then—and I found the story riveting and the characters intimidatingly cool. Jake Barnes, an expat in postwar Paris, living large on the dollar-to-franc exchange rate, eating well, getting tipsy every night in bars I could scarce imagine, hopelessly in love with Lady Brett Ashley, who remains, for me, the novelistic paragon of sexy cool. Who wouldn’t want to live like that? When my generation—the one whose one-letter name my coeval Elon Musk has appropriated for his hell-site—began to be called the “New Lost Generation,” I (idiotically) thought this was a good thing. “Lost” to me meant “off the beaten path,” with a hint of being fallen, like so many bad angels.

At seventeen, I did not understand that the reason members of that original cohort were so disaffected was because they had lived through both the Great War and the subsequent Spanish Flu epidemic; that they were in Europe mostly because they were heavy drinkers and booze was illegal in the States; that Jake Barnes could not get with Lady Brett because his junk had been blown off in the war; that as bad as things were in 1914, they were going to get exponentially worse a quarter century later; that by “lost,” Gertrude Stein really meant “fucked.”

The writer Stefan Zweig had the good fortune to be born into a family of means in cosmopolitan Vienna, which at the turn of the century was the cultural capital of Europe. He also had the misfortune of being born in Austria in 1881. Of all the lost members of the Lost Generation—“our unique generation, carrying a heavier burden of fate than almost any other in the course of history,” as he puts it—few lost more than Zweig. “We have all, even the least of us, known the turmoil of almost constant volcanic shocks suffered by our native continent of Europe, and the only precedence I can claim for myself among a countless multitude is that as an Austrian, a Jew, a writer, a humanist and a pacifist I have always stood where those volcanic eruptions were at their most violent.”

The World of Yesterday, the memoir he finished in February of 1942, is a nostalgic look back at his childhood in Austria before the collapse of the Hapsburg empire, but it is also a chronicle of loss. Zweig was sixty when he wrote the book, in exile—a second or third exile—in Brazil. He’d seen enough horrors for many lifetimes. As he notes, the Vienna of his youth was lost and gone forever: a great city, the seat of imperial power, reduced to a German provincial town.

Between the wars, Zweig had become one of the most popular writers in Europe, if not the world. Then another Lost Generation Austrian came to power in Berlin, and Zweig, a Jew, had to flee. He was in London first, then Bath; but that was not far away enough. The Sonderfahndungsliste G.B., the so-called “Black Book” of British residents who the Nazis would round up after their planned invasion of England, listed Zweig among those subversives. So he crossed the Atlantic, residing in New Haven, then in Ossining, New York, and then, ultimately, Petrópolis, a city in Brazil with a large population of German speakers.

Zweig writes in his foreword:

We have made our way through the catalogue of all imaginable catastrophes from beginning to end, and we have not reached the last page of it yet. I myself have lived at the time of the two greatest wars known to mankind, even experiencing each on a different side—the first on the German side and the second among Germany’s enemies. Before those wars I saw individual freedom at its zenith, after them I saw liberty at its lowest point in hundreds of years; I have been acclaimed and despised, free and not free, rich and poor. All the pale horses of the apocalypse have stormed through my life: revolution and famine, currency depreciation and terror, epidemics and emigration; I have seen great mass ideologies grow before my eyes and spread, Fascism in Italy, National Socialism in Germany, Bolshevism in Russia, and above all the ultimate pestilence that has poisoned the flower of our European culture, nationalism in general. I have been a defenceless, helpless witness of the unimaginable relapse of mankind into what was believed to be long-forgotten barbarism, with its deliberate programme of inhuman dogma. It is for our generation, after hundreds of years, to see again wars without actual declarations of war, concentration camps, torture, mass theft and the bombing of defenceless cities, bestiality unknown for the last fifty generations, and it is to be hoped that future generations will not see them again.

It is horrific to experience all of those things, to live through the horrors. But to do so when you thought, when you genuinely believed, that humanity was past all of that, that the European peace, and the great culture and liberty that comes with it, was here to stay, only to realize that you were wrong—that your faith in reason and science and art and goodwill and love was ill-founded? That is devastating.

Zweig couldn’t take it anymore. He finished his memoir, sent it off to his editor, and the next day, February 2, 1942, he and his second wife—who had been his longtime secretary—swallowed enough barbiturates to end their suffering. They died holding hands. He left behind a short note:

Declaration

Of my own will and in clear mind

Every day I learned to love this country more, and I would not have asked to rebuild my life in any other place after the world of my own language sank and was lost to me and my spiritual homeland, Europe, destroyed itself.

But to start everything anew after a man’s 60th year requires special powers, and my own power has been expended after years of wandering homeless. I thus prefer to end my life at the right time, upright, as a man for whom cultural work has always been his purest happiness and personal freedom—the most precious of possessions on this earth.

I send greetings to all of my friends: May they live to see the dawn after this long night. I, who am most impatient, go before them.

Stefan Zweig, Petrópolis, 22.2.1942.

The long night was not nearly over. As Anthea Bell, who translates the book beautifully into English, notes in her 2009 introduction, Zweig didn’t know the half of it. It is, she writes, “a shock to the modern reader to realise that at the time of his death he did not know the full horror of what was still in store….When Zweig was writing, he describes the fate facing a Jew under Hitler in 1939—deprived of all his possessions, he would be expelled from the country with only the clothes he stood up in and ten marks in his pocket. It was certainly bad enough, but there was worse to come.”

And here we are again, eight decades later, at the precipice of something globally awful. Madmen call the shots in Russia and Iran and North Korea. China is a brutal dictatorship with ambitions of empire. The crooked, evil Bibi seems bound and determined to escalate war in the Middle East, if only to avoid his own prosecution, with little regard for the deleterious effects of his actions on Israelis as well as Jews in America and Europe. Traitors in Britain kneecapped that country with BREXIT. Traitors in Hungary and Turkey prevent the EU and NATO from united action against the totalitarian march. Fascism is waxing in Canada, of all places.

And here in the United States, Trump openly invites comparisons to Hitler, reviving the ultimate flower-poisoning pestilence of nationalism. His flunky Kash Patel hints at the existence of a Sonderfahndungsliste MAGA. A corrupt, reactionary Supreme Court is steadily stripping our rights away. A small but vocal minority of NRx weirdos want to end democracy and establish a dictatorship. And a third of the country are too wrapped up in god knows what to bother to vote, while one of the many foul byproducts of Bibi’s ill-conceived and horrific invasion of Gaza is that a lot of idealistic young Americans now view President Biden—the last bulwark against totalitarianism in this country—as the problem.

The New Lost Generation is not out of the woods, not even remotely. As bad as things were under Trump, as many Americans who died due to his negligent mismanagement of the pandemic response, we were lucky to escape with the federal government intact. That will not happen if that monster is reinstalled in the White House.

We must understand the woe suffered by the Lost Generation, or we will be yet another sad example of those unwilling to learn from history repeating it. As Zweig writes in his foreword, “But if we can salvage only a splinter of truth from the structure of its ruin, and pass it on to the next generation by bearing witness to it, we will not have lived entirely in vain.”

There is still time. One thing that has not yet been lost to us is hope.

ICYMI

With LB sick with the flu, I summoned my inner MTV veejay and went through the karaokes, fake ads, and other comic bits we’ve produced for The Five 8:

First Take

My friend David First, the supremely talented guitarist and composer—as well as my wife Stephanie St. John’s music teacher and artistic mentor—was inspired by the Israel-Hamas War to write and record a new song. He usually eschews songwriting of this kind for more complex avant-garde compositions involving drones, so when he writes and records a new single, it’s always a big deal. “Next of Kin” features Yvette Massoudi, a recipient of the 2022 NYC Women’s Fund for Media, Music, and Theater grant, on vocals. And David will probably object to my phrasing it this way, but it’s a banger.

Please listen and share:

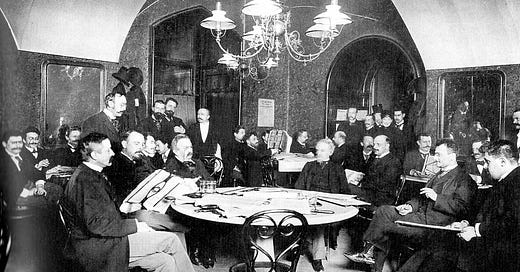

Photo credit: Wikipedia. Café Griensteidl in Vienna, sometime before 1897. Zweig referred to it as the “headquarters of young literature.”

Powerful piece Greg. We are indeed at an inflection point. Are we destined to see history repeat itself? I sincerely hope not. Thanks for the thought provoking read with coffee this morning.

Hitler was obviously a "true believer," and I don't think Trump really is. Trump will go whichever way the wind blows him as long as it glorifies him. If things changed in some VERY WEIRD way and suddenly Democrats and liberals found their true voice through Trump, he would be touting pro-choice positions, "one person, one vote" policies, and start working on breaking up corporate monopolies that are hurting Americans. Trump is not the REAL problem; he is only the mouthpiece that wants to be in the news 24/7/365. He is far too self-involved to be anything else.

It's people like Bannon, and to a lesser extent Kash Patel, who are the real danger. The six-minute clip on Media Matters linked in the column above shows what a wild-eyed freak like Bannon WANTS to do in a Trump 2.0 term. In the clip, Patel was referencing a script in front of him, Bannon's words came from his cold, black heart -- no script needed. Bannon has made pronouncements before like this, most famously that he would destroy the "administrative state." He's WAY beyond that now. He's looking forward to prosecutions of politicians, members of the media, and anyone else who gets in his way. I'm sure in the end, Bannon's ultimate goal is executions for "treason" of some of these people. He's extremely dangerous and his liver may not take him out in time. He might actually be able to be a part of a Trump 2.0 term. Secretary of State, maybe? It sounds like Patel will be the Director of the CIA, so he's all set! Stephen Miller, Secretary of Education? Sounds about right.

But when the mouthpiece comes out and starts in with stuff like, “They’re poisoning the blood of our country,” it's time to REALLY pay attention. This kind of statement has not only been said at several rallies but is far beyond references to "vermin." Someone probably told him that "vermin" wasn't quite far enough, "you really should start talking about how the immigrants are poisoning the blood of our country, and sir? Make sure to punch up the idea that they're poisoning the BLOOD of our country."

He's going to keep making these kinds of statements, and although I read "Mein Kamph" years ago (what a fuckin' whiner that Hitler was, just like Trump), I don't remember what else he might pull from it for his use, but I'm sure others in his orbit will find something appropriate as time goes on. And I wonder how long our MSM will continue to report these statements as if they're aberrations, and keep tiptoeing around the Hitler rhetoric? WE ALL KNOW THIS GUY! These are not aberrations; this is well-orchestrated rhetoric meant to be one more thing that we're supposed to normalize. How much longer until we hear, "folks, I've always been right, they DID bring crime and they ARE rapists. I told you that from the first day I ran to be your favorite president. What we need now is a FINAL SOLUTION to the immigrant problem." How much longer? After Iowa? Or will he save it for the summer, so Don Jr will love it? And how many "final solutions" will he end up needing, do you think? Because "we got a lot of problems."

This is no longer a marathon, it's an eleven-month sprint. WE MUST stop this man from ever taking office again. He's the mouthpiece, but he will hold the power if he gets in there, and as the avatar for the farthest of the far-right, they will bring in their own form of Nazism as sure as the sun rises in the east. VOTE because your life depends on it, and if we don't keep him out, it will likely be the last election. Hyperbole? Listen, watch, and think again.