Dear Reader,

Back in college, I took a class in Victorian Literature. My professor, Paul Betz, was, and is, considered the greatest living Wordsworth scholar. We read a lot of Thomas Hardy in that class, and it was in the context of those discussions that I learned about hap.

An archaic word these days, a truncation of the old-timey happenstance, to Victorian novelists and poets, hap was a BFD. It means “chance or fortune,” per the dictionary, but there was more to it than that. Hap was when some random unforeseen event mucked up the smooth contours of the plot, throwing the action into chaos. In the Hardy novels, it usually manifested as I wrote you a letter and slipped it under your door, but it went under the carpet, and you didn’t discover it until it was too late!

However advanced our technology, however good our intentions, however total our preparation, there are always things that happen out of the blue that we have not accounted for, that were impossible to foresee: the First Communion luncheon turns into a super-spreader event; a sickness in the family prompts you to push your flight to California from September 11, 2001, to the next day; the supermarket where you go to pick up milk on a Saturday afternoon is the same one targeted by a radicalized, racist, homicidal killer; a tree falls on you while you’re out jogging, paralyzing you.

Pull back a bit, of course, and everything is hap: that our parents came together when they did, that their parents came together when they did, and so on to infinity. Life is a crapshoot. One of the wisest sentences ever constructed, it seems to me, is Reinhold Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” Part of what Niebuhr prays for is not to waste time and emotional energy railing against things that are impossible to control—in other words, the forces of hap. Because hap cannot be countered, hap must be accepted. Which is easier said than done, because hap is scary. I know I’m terrified of hap. When the Wheel of Fortune spins, as anyone familiar with Pat and Vanna knows, it may land on BANKRUPT!

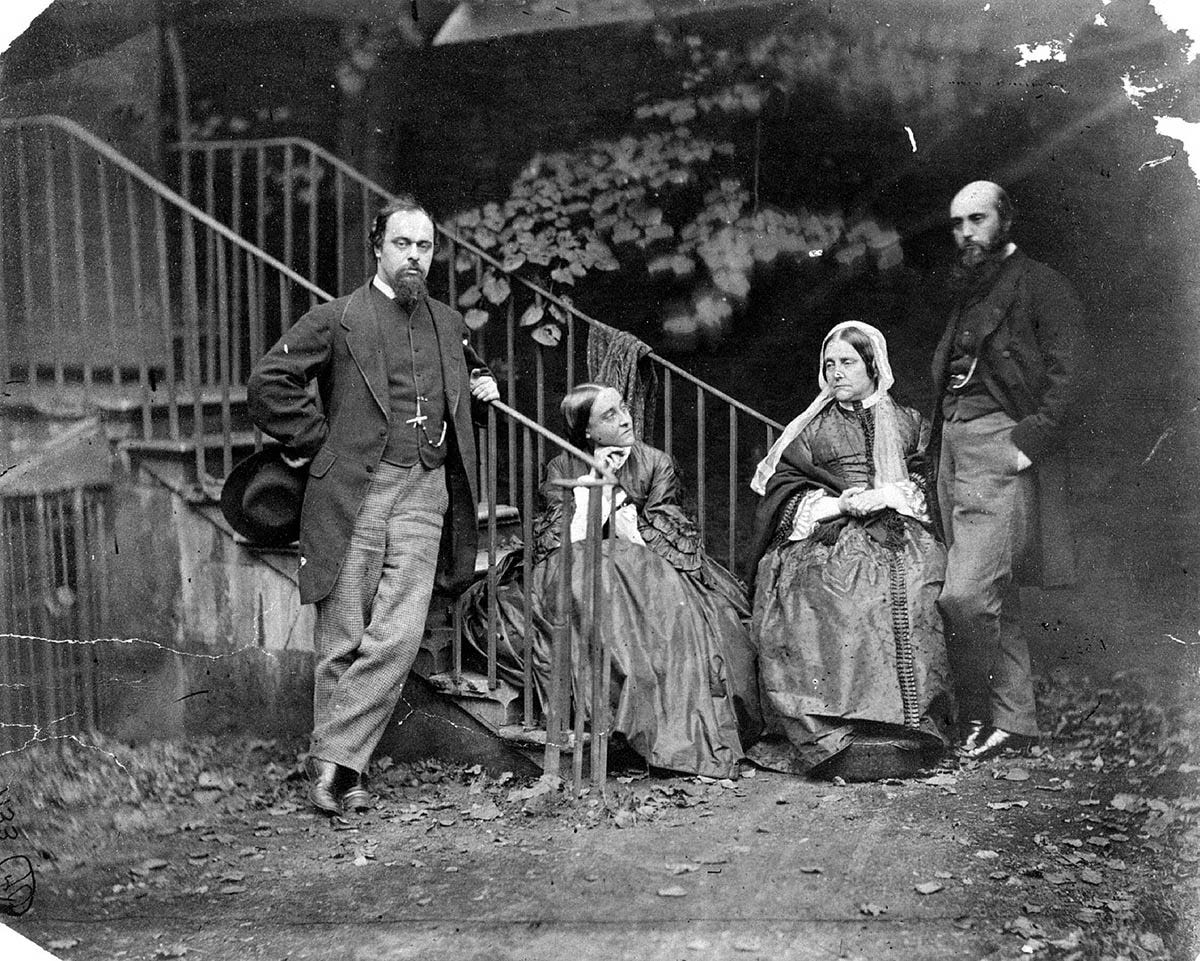

I write about hap because it factors into the last lines of this “Sunday Pages” song by the British poet Christina Rossetti (1830-94). She was born into an artistic family; her brother Dante, a painter, was a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and her other siblings were also writers. Her work was championed by Swinburne, Tennyson, and Gerald Manley Hopkins. The photo at the top of the page, of Christina, her mother, and two of her brothers, was taken by their friend Lewis Carroll—that Lewis Carroll.

The word haply is similar to happily, especially in lyrical verse, when our brains are accustomed to chopping off unnecessary syllables. I think this is by design, and that Rossetti intends us to read both words simultaneously. Similarly, the word wilt, repeated twice in the two lines the end the first stanza, has two meanings: the Old English will, and the botanical wilt. Finally, Rossetti’s description of death as “the twilight / That doth not rise nor set” is, I think, a lovely if melancholy characterization of the sweet hereafter:

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

ICYMI: Lincoln’s Bible and I have a live YouTube show on Friday nights called “The Five 8.” This week, our guest was Arthur Snell, host of the podcast “Doomsday Watch,” author of the upcoming book How Britain Broke the World, and the managing director at Orbis. Here is a replay:

Timely. The hap hit me this week, losing my comfortable executive job Friday morning, after 14 years of loyalty and contributions and being discarded in a surprise re-org. Life is indeed a crapshoot.

Those Victorians still have a lot to teach us about love, duty, and honor—lessons completely lost in this post-modern dystopia. What they were most right about is that society must relearn those lessons in every generation in the face of incredible surges in technology and science. Victorian England created railroads, postal service, police, public sanitation, fundamental new laws of physics and science, modern education (instead of preparing every student for a life in the ministry), they explored the world’s darkest places, and wrote wonderful literature. My PhD is a study of the works of Tennyson, who I love still after all these decades. I may be one of only three or four living people who has read his plays, and yet at his death the public was certain he would be remembered as a playwright equal to Shakespeare. Your brilliant essay awakens in me this Sunday morning a broad range of emotions and reminds me of how much I loved being immersed in the literature of great minds. Matthew Arnold, Wordsworth, Keats, Browning, Swinburne (who leapt on the Victorian stage like a satyr at a tea party), Tennyson, and all the rest. Thomas Carlisle gave the lectures that today have become TED talks. Maxwell gave us the laws of thermodynamics. John Henry Newman has been canonized more for his miraculous writing than for any miracles of faith. It was a fascinating age, akin to our own in the way advances in STEM overturned all the old orders. About Rossetti, yes yes yes. Thank you. Thank you.