Sunday Pages: "When This Is Over"

A new album by Heylo

Dear Reader,

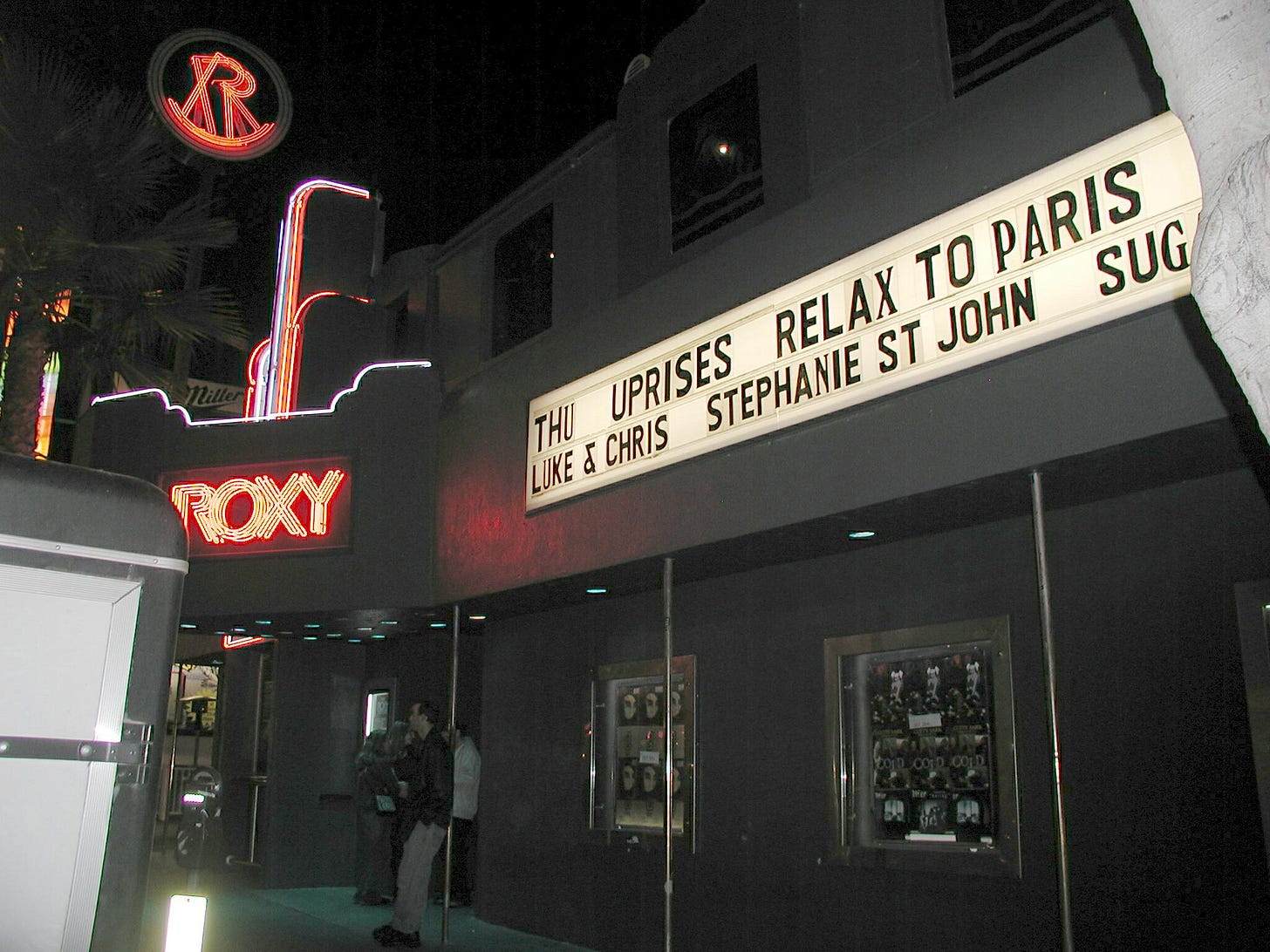

When my wife and I first started dating, 22 years ago this month (!), she was fronting her own band. She’s Stephanie St. John—that was the name on the marquee—and the bassist and drummer were both named David, so they were known as Stephanie and the Davids. They played small clubs in Manhattan: the Blue Room, Brownie’s, the C-Note, Sidewalk Café, CB’s Gallery.

Those shows were fun—some of my happiest moments in that time of my life. I’d sit up near the front, bouncing up and down to the beat like a piston. The two Davids were both incredible musicians, and Stephanie was terrific—the voice, the look, the comic banter between tunes, and, especially, the music. There was the occasional cover thrown in for fun (“Jolene,” “Dreaming,” and the absolutely sick rendition of “I Feel Love”), but the songs were all her own. And they were fantastic!

It’s really hard to have your own band in New York. There is no “homecourt advantage.” There are so many other things going on, so much to do, that’s it’s almost impossible to build up a following. The men who managed the nights of music at those venues tended to be giant assholes with even more giant God complexes. The other bands usually just wanted you to die, so they could play a longer set. Some nights the venues were packed to the gills; other nights, the bass player’s wife (hi, Meredith) and I were the only people there who had come specifically to see the show.

And there were snafus. Broken guitar strings. Feedback on the monitors. One night at Sidewalk Café—the air conditioning always so gloriously cold in the summer—David the drummer was late, so the show started without him. He brought in his kit through a door right behind the stage, set it up, and started playing halfway through the second song. Rock ‘n roll!

In 2000-01, Stephanie and the two Davids spent a few weekends in Delaware, where David the drummer’s cousin had a studio. (Those were the days when everything had to be recorded in a studio.) They produced an album called Cinderella’s Dead, which title came from the first line of one of her signature songs, “Beaver Dam:”

Cinderella’s dead, and the prince is gay,

And we all confessed to no waxing today.

In those days, it was pulling teeth to get anyone to listen to your stuff. People still called the Internet the World Wide Web. There was no Spotify, there was no YouTube, and if iTunes existed, it was in the larval stages. We had to press copies of the CD, and then send it out to music magazines hoping for reviews—the music biz equivalent of lighting money on fire. Despite the long odds, she managed to secure a few notices, including in the Village Voice. (Bless your heart, Chuck Eddy!) There was a raucous CD release party at Acme Underground that packed the house—and since admission included limited open bar, got everyone nice and toasty for the show.

The performances were always stellar, but when everything was clicking—when there were enough people in the audience, when the PA was loud enough, when Stephanie was really feeling it, when the two Davids were wailing—they were positively magical. They had “It.” But there are so many elements to this, so many things that have to be just so, that “It” is almost impossible to sustain. Entropy works against rock bands, against singer-songwriters, against all live musical acts. It is a destructive force of nature that all artists must combat—whether it’s Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney, Billie Eilish and Lana Del Rey, or Stephanie St. John and the Davids. Part of the appeal of watching a band perform is that we are witnessing an act of courage, of fighting against these forces—not unlike watching a surfer catch a really great wave.

Not long after they flew to L.A. and played the Roxy and the Whisky a Go Go, David the drummer quit, to join another band—a big blow to my wife’s self-esteem. Stephanie found another drummer, also named David. One of my oldest and dearest friends, Michael Preston—a brilliant guitarist who had played in a band with me in high school, and whose own band, Shagg, was also feeling the effects of rock ‘n roll entropy—joined as well. She also enlisted one of her old and dear friends, Kim, to sing backup, along with a new New York friend, Michelle.

The new band was called Mimi Ferocious (which is a nickname my mother gave my little brother Jeremy when he was a baby and in a particularly colicky mood). They recorded a kick-ass album called 250 Times Sweeter Than Sugar that remains transcendently good. On “Chariot,” Stephanie achieved rock lyric perfection when, no matter how well she enunciated, the line “a shell on a broken beach” always sounded like “Michelle is a fucking bitch.” Sugar contains what is probably my favorite of her tunes, “Rocket Song.” I was privileged to witness that song come together over the course of a few weeks, like Ringo watching awestruck as Paul gave birth to “Let It Be.”

And then entropy reared its ugly head.

David the bassist moved to Westchester. Michael moved to New Jersey, where David the new drummer already lived. Stephanie got pregnant, and once our son was born, we high-tailed it upstate. Rehearsal, already an expensive inconvenience in the city, became near impossible.

The band’s last hurrah was at Mamapalooza, an outdoor concert for musician moms held in 2006 at Kensico Dam. Stephanie, visibly pregnant, gave a soaring performance as I danced below the stage, our one-year-old in a metal contraption on my back, bouncing up and down to the beat. It was bittersweet. When that show was over, we all sort of knew the show was over.

For my wife, most of the next 15 years were a period of creative frustration. She wrote a lot of songs, but never seemed satisfied with them. She would still play guitar in the house, but not nearly as much as she used to, not with two little kids around. Sometimes she would find local musicians to collaborate with, but for one reason or another, it never worked out. She played solo shows here and there, but she didn’t seem to get out of them what she wanted or needed. Her deep talent was still readily apparent, at least to this longtime observer, but her confidence was shattered. And other than encourage her, there wasn’t much I could do about it.

There was one song she started writing almost 20 years ago, when we still lived in the halfway house to leaving the city that is Astoria. It had this incredible propulsive bass line and a haunting undertone that was like a sort of musical incantation. Through the years, the lyrics evolved, morphed, changed, but the chorus stayed the same:

Baby I would have given you hipster heights, I—

I would have given you lipstick fights, I—

I would’ve if I could.

But down in Brooklyn, down in the basement,

There’s a rhyme and a reason for it,

Adjustment season for it.

Would her creative powers ever return? She had her doubts. But I knew she wasn’t finished, because that song remained. It had to come out, in some final form. It was too good not to. But what was the final form? And when would it reveal itself? She’d spent over 17 years tinkering with it, working around its edges.

As our kids hit high school, three things became clear: 1) Her creative pilot light was out, 2) someone else had to help fire it back up, and 3) that someone couldn’t be me. And then, just as quarantine began, she hooked up with Liam Wood, a wonderfully talented guitarist who had been our son’s piano teacher. At long last, all those years of pent-up musical frustration came pouring out of her. The two of them—Heylo—began collaborating, working on an album which became When This Is Over.

Now, almost 16 years since that last Mimi Ferocious gig at Mamapalooza, Stephanie is ready to release the fruits of their labor to the world:

One of those fruits is that song she’d spent almost two decades perfecting. I still call it “Down in Brooklyn,” but the real title is “As Long As I’m With You,” and it is sublime:

Entropy is a terrible force. Being a singer-songwriter is a particularly grueling art form—only acting and stand-up comedy require more vulnerability, and thus more abuse to the ego. For Stephanie to fight against these forces, to not give up after so many years at sea, and to produce something this fucking good, is a monumental achievement. I can’t tell you how proud I am of my wife today.

The good news is, there are no compact discs to be pressed by the boxload and mailed to magazines. There are no asshole club managers to brown-nose. There are no tour dates to promote. The album is available for purchase on Bandcamp, but what Stephanie wants more than anything is just for people to listen. (And if someone doing the listening has the juice to get some of these songs onto the soundtrack for a movie, a TV show, or a commercial, so much the better!)

What a blessing, in this day and age, that the act of listening doesn’t require a trip to Tower Records, or the purchase of a physical object, or a delay of gratification.

All you have to do is press play:

And if you’d rather not use Spotify—eat shit, Joe Rogan—the album is available to stream at Apple Music, CD Baby / Hear Now, Bandcamp, and Pandora, and there are videos available on the Heylo YouTube page.

Thanks for listening, and happy Valentine’s Day!

Photos: Stephanie and the Davids at the Roxy in L.A., 2001.

This is my favorite of all your pieces I've read. Not only is it a beautiful tribute to your wife and your love for her, it holds many life lessons for me. Thank you so much. Please tell your wife "Thank you" for me for being true to her heart and her gift in the face of the entropy you describe so well. I really needed this today.

What a beautiful love letter and tribute. Happy Valentine’s Day you 2