IN OLD MOVIES, when a child coughs, it means she will soon take ill and probably be dead by the next reel. Nowadays, this feels almost ridiculous, straining our 21st century credulity, but for most of human existence, that happened with terrible frequency: cute little kids came down with a fever or a sore throat, and within a week, they breathed their last.

Diphtheria was one such ugly malady that ravaged children. In places like the tenement houses of New York—so many large families crammed into tight little spaces—the Corynebacterium diphtheriae bacterium flew hither and yon, conveyed upon moist droplets propelled into the stale air when infected humans coughed and sneezed on each other. (Fun fact: The reason Lower East Side apartments get so famously hot during the winter, to this day, is to allow for tenants to keep the windows open, to help ward off disease).

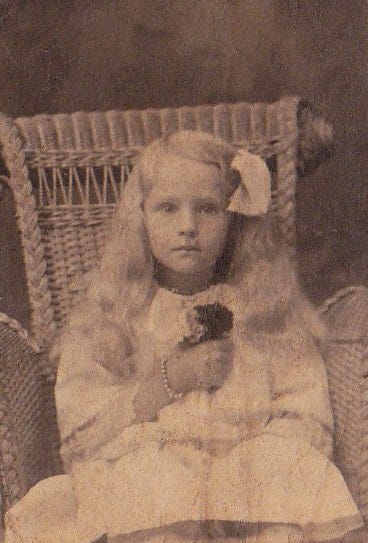

New York City suffered through major diphtheria outbreaks every few years, from the 1860s well into the 20th century. Thousands of residents died every year of diphtheria. Per the 1890 census, it was the sixth-leading cause of death in the city. My great-great-uncle—the older brother of my father’s grandmother—was one of those tens of thousands of data points, succumbing to the disease in 1893. But it wasn’t just poor immigrants. Princess Alice, the daughter of Britain’s Queen Victoria, died of diphtheria in 1878; in 1904, diphtheria claimed the life of former President Grover Cleveland’s 12-year-old daughter, Ruth Cleveland—the “Baby Ruth” of candy bar fame (pictured above).

Diphtheria was a nasty, nasty business. As the CDC describes: “The bacteria make a toxin (poison) that kills healthy tissues in the respiratory system. Within two to three days, the dead tissue forms a thick, gray coating that can build up in the throat or nose. Medical experts call this thick, gray coating a ‘pseudomembrane,’” or a diphther. “It can cover tissues in the nose, tonsils, voice box, and throat, making it very hard to breathe and swallow.” In extreme cases, that gray coating got thicker and thicker until the air passage was blocked off entirely, and the infected child suffocated to death. Can you imagine watching your kid die this horribly?

As the disease ravaged New York and elsewhere, doctors, scientists, and public health officials—folks like Emil Roux, Paul Ehrlich, Béla Schick, William Park, and Anna Williams—were busy developing a vaccine and implementing its rollout. Park, the laboratory director at the New York City Board of Health from 1893 to 1936, launched a large-scale study of immunization of the disease in the Five Boroughs. His push to get children vaccinated saw the rates of infection plummet after the late 1920s. By the time FDR took office, diphtheria was more or less eradicated from Gotham.

Nowadays, no one in the United States gets diphtheria. Other than an outbreak in Russia in 1994—we can probably blame that, too, on organized crime—there have been only a handful of cases anywhere on earth in the last 40 years. The reason why is that infants are given the vaccine. The “dip” in “dip-tet” stands for “diphtheria.” Kids can’t go to school unless they show proof of immunization.

There was vaccine hesitancy back then, too. In the early 20th century, this stuff was new, and therefore scary. Sometimes batches of the vaccine became contaminated, and kids died as a result. Even so, science won the day, and a nasty disease that had afflicted tens of thousands of people every year was eradicated. It probably helped that there was no social media, or TV, or even radio at the turn of the century, so President McKinley couldn’t take to the airwaves to announce, against all logic and available evidence, that diphtheria was no worse than the flu, that wearing a mask to prevent its spread was un-American and stupid, and that the new vaccine contained a microchip so unsuspecting citizens could be monitored by John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan. Nor did he hold rallies in crowded indoors spaces where the disease might more easily be spread, in which he blamed China, Democrats, and “fake news” for the problem. (None of this prevented McKinley from being assassinated, however).

In 2021, there’s no excuse for such hesitancy. We have the benefit of history to look back on. We can point to the success of campaigns to end diphtheria, and smallpox, and hookworm, and mumps, and measles. It takes a special kind of entitlement—and a special kind of ignorant—for a parent to look at that list of terrible infectious diseases kids no longer have to worry about and say, “You know what? Fuck it, I’ll take my chances.”

There will always be people who don’t trust the scientists, who believe the disinformation, who put themselves and others at great risk because they lack the intellectual or moral capability to grok how this stuff works. My brother, an ER nurse, tells of a staunch Jehovah’s Witness who would not allow her grandson to have a blood transfusion, because it was against her religious beliefs; denied necessary medical care, the boy died. I speak of people like that.

In 2020, those stunoti were in charge of our government. The pandemic response was run by the three-headed monster of Donald John Trump, Mike Pence, and Jared Kushner, and you would be hard-pressed to find a troika more hapless and corrupt. For medical advice, they turned to evangelical Christians like Robert Redfield and Deborah Birx—doctors who, as Nina Burleigh explains in her excellent new book Virus: Vaccinations, the CDC, and the Hijacking of America’s Response to the Pandemic, were inspired to get into virology during the AIDS crisis, because they saw themselves as moral crusaders. Small wonder that half a million Americans needlessly died.

Reminder: Trump knew what covid-19 was. He knew back in February that it was much more deadly than the flu. He didn’t give a shit. He and his Slenderman motherfucker of a son-in-law sabotaged the coronavirus response, greenlighting a Blue State Genocide, because they thought, small-minded idiots that they are, that it would help him win re-election. As this went down, the alleged Christian Pence, Trump’s Gimp, who as governor of Indiana had exacerbated an HIV outbreak because of his ideological contempt for Planned Parenthood, smiled beatifically in the background and did nothing, I guess because there are not enough examples in the Gospels of Jesus healing the sick.

This was nuts as it was happening. In hindsight, it looks like absolute madness. “We were pelted with WTFs,” as Burleigh tells me on today’s PREVAIL podcast.

And yet despite this historical bungling, and against all odds, our scientists managed to develop a vaccine. If covid-19 happened 25 years ago, Burleigh explains, there would be no such thing. It is only because of incredible advances in genetics in the last quarter century that we managed to create this wonderful thing. And as soon as President Biden took over, and actual competent people were once again in charge of the federal government, boom, the vaccines were rolled out, and everyone who wants one got one (or got two, as it were).

As Nina says, this is a modern-day miracle. With so much bad in the world, it is important to acknowledge—and to marvel at—the amazing things that happen. The creation and rollout of the covid-19 vaccine is an historic achievement, a triumph of human ingenuity. Paul Simon was right: these are the days of miracle and wonder.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

E19: Pelted with WTFs (Virus & Vaccine, with Nina Burleigh)

Description: Greg Olear talks to journalist Nina Burleigh, author of the new book “Virus: Vaccinations, the CDC, and the Hijacking of America's Response to the Pandemic,” about the virus, the failed pandemic response of the Trump Administration, and the modern miracle that is the covid-19 vaccine. Plus: the biggest event of the summer comes to the world-famous Lorain County Fairgrounds.

Buy Nina’s book:

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/691352/virus-by-nina-burleigh/

Follow Nina on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/ninaburleigh

Photo credit: (Baby) Ruth Cleveland, one of thousands of cute kids who died of diphtheria before there was a vaccine. And, schoolchildren in NYC line up to get the diphtheria vaccine, 1920s.

And here I am, old as dirt, managing to get educated over the past year or so on infectious diseases, pandemics, and the like, and did not know until this column, the etymology of the "Baby Ruth" bar. I've always thought the name had something to do with the baseball player. STILL learning something new every day! Thanks, Greg!

Stunoti? I love it and have no idea whence it comes and what it means!