Triumph of the Yuppies

A discussion with Tom McGrath, former editor-in-chief of "Philadelphia" magazine and the author of the new book "Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation"

Tom McGrath, my guest on today’s PREVAIL podcast, was the editor-in-chief of Philadelphia magazine, as well as chief content officer of Metro Corp., the parent company of Philadelphia and Boston between 2010 and 2020. Under his leadership, the magazines won more than fifty awards for editorial excellence. In 2022, he was named Writer of the Year at the National City and Regional Magazine Awards. He’s written two previous books: MTV: The Making of a Revolution, and, with John Basedow, Fitness Made Simple. His Substack is called Common Good.

His excellent new book, Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation, traces the development of the Young Urban Professional: how the movement started, what defined it, who was part of it, how they changed the culture, and what their ascension in the 1980s portended for the future.

Here are three takeaways from our discussion:

Yuppies were not all bad, and certainly not all death-deserving scum, but their collective impact upon the business world, and capitalism in general, exacerbated income inequality.

A yuppie is, or rather was, in the go-go 1980s, a young city-dwelling professional, almost always with a degree from a fancy college. Yuppies were the first foodies and the first fitness buffs. They liked new technology and gadgetry. They revitalized (if you think it’s good) or gentrified (if you don’t) neighborhoods in big cities, most notably New York’s Upper West Side, which became a sort of Yuppie capital. And they had an outsized impact on all aspects of society: culturally, politically, economically.

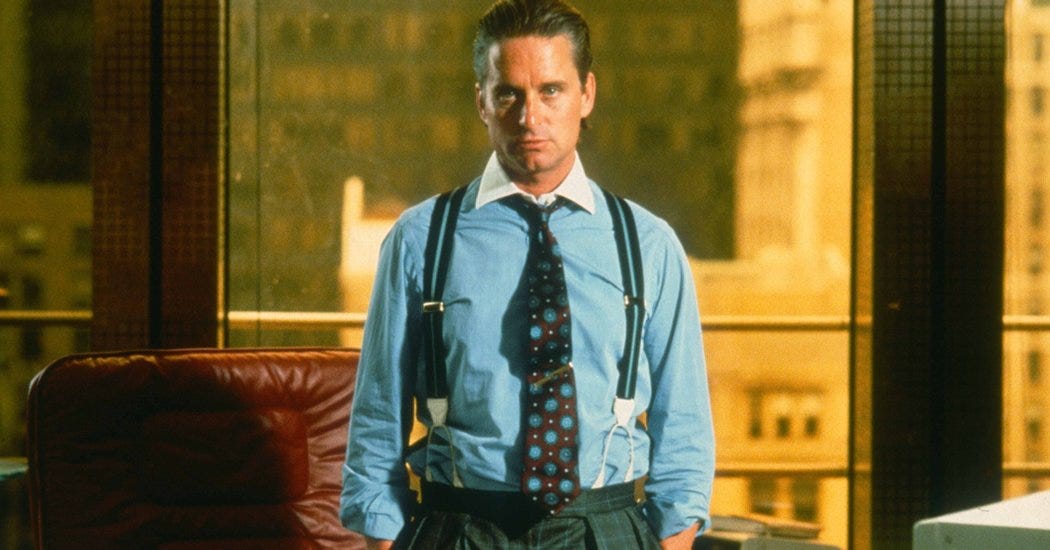

Yuppies are known by their affinity for Izod Lacoste shirts. But the open-mouthed alligator logo is appropriate, because in the business world, they were rapacious and ruthless. Gordon Gekko, Michael Douglas’s iconic character from the Oliver Stone film Wall Street, did not actually exist. But his ethos was all too real.

One of the avatars of this new take on capitalism was Michael Milken, who made a fortune in junk bonds, went to prison, and was the beneficiary of a Trump pardon. I didn’t know much about him beyond that, but he’s a complex and fascinating character.

“You know, I went into the book knowing a little bit about Milken, and I think my vision of him was kind of cartoon rapacious Wall Street trader who wanted nothing more to make money,” McGrath tells me. “And let’s be clear: he wanted to make money, and he made a ton of money doing what he did. But he’s more complicated than that, because he really wanted to change the way the system worked. His view was that finance in particular was kind of an old boys’ club sort of game—you had to know somebody who knew somebody to get money to start a company or to expand your company. And he wanted to change that, and he did it…[H]e figured out a way through junk bonds that companies that otherwise weren’t going to get financing could get it through junk bonds.”

This expanded the opportunities for a lot of entrepreneurs who otherwise would have been shut down. It also made Milken insanely rich.

“To me, where I tend to lean negatively on Milken is that he makes all of capitalism about the return to the shareholder, because that’s his piece of it,” McGrath continues. “He wants his money back. He wants shareholders to be rewarded. And look…you can’t have capitalism without shareholders getting rewarded. But part of what I talk about in the book is that in the 80s, there is such a shift from ‘employees can benefit from a strong company, communities can benefit from a strong company, obviously customers benefit,’ which was a previous version of capitalism. In the 80s, we swing completely to, ‘unless the shareholders are making every dime that they can, we’re not interested.’ And I think Milken is part of that movement and part of what makes that happen.”

The credo of “shareholder über alles,” in my view, is the primary reason this stage of capitalism sucks: why income inequality is so gaping, why communities fail when local industries shut down or relocate, why companies move from state to state in search of little tax incentives with nary a thought to all the negative baggage that comes with it, and so on. Milken followed the credo as an investor; Jack Welch did so as a CEO, and for that, merits his own extra brimstony circle of hell.

McGrath explains:

Yeah, so Welch becomes the CEO of General Electric in 1980, 81. And at that time GE is one of the iconic American companies. And it was literally started by Thomas Edison in the 1880s. And not only is it a successful company in the sense that it makes money, but it develops these products that people use for a hundred years. I mean, we start with the light bulb, right? But when we get into the first washing machines, then it gets into defense contracting, but things that are useful. It’s very big in the war effort in World War II. And so it’s a company that is both making money, but also innovating in a way that actually helps the society move forward. Welch takes it over and his sense is that it’s quote underperforming because the stock price is not as high as he thinks it should be. And so over the course of several years, he remakes the company, first of all, by either selling off divisions of it that are profitable—they’re just not profitable enough.

And in a lot of other cases, he just lays off people and eliminates jobs, which not only leaves literally tens of thousands of people out of work, but then communities are being decimated because GE was sort of the big employer in a community. So the swath of destruction that follows Jack Welch is pretty estimable….He becomes this spokesperson for “shareholder value is the thing that matters most.”

And even while he is gutting all these jobs and changing GE, the stock price is going up. So he wasn’t wrong in the sense of, “If I do this, the stock price will go up and shareholders will benefit.” It’s just there was no acknowledgement of the destruction he was causing on the other end of that equation.

To paraphrase the Mandalorian: this is not the way.

We give the media a lot of shit for how they cover Donald Trump, and rightly so. But there’s no simple formula for how to cover him.

I did not watch, and will not watch, Trump’s hatemongering acceptance speech last night. It had an 80s flavor to it. He was introduced by a retired pro wrestler popular in that decade. He wore a prop bandage on his ear that looks like a maxi pad. He ranted like a grievance machine. But how do you cover something like that?

“I think difficult and complicated because if the only thing that the media does is just tell you, in every single story that they do, how terrible Donald Trump is, how much he lies, how corrupt he is—if that’s the only thing that anybody says about him,” McGrath says, “eventually you just tune that out, right? Like, okay, you’ve told me that before. Is there anything new with Donald Trump?”

He continues:

And so I think journalists are compelled to cover what’s new. Now, what’s new and what’s old, it might be the same thing. [Trump is] just displaying his autocracy in a new sound bite this time. But because journalism covers what’s new, that’s what gets covered. So, I mean, I know journalists get criticized over this, but I don't know a lot of other ways you could do this. I mean, I think they do a good job of reminding people, you know, [that] there is no evidence for this or this is literally factually incorrect. I mean, so I think you can do that to sort of fact check them as we’re going along.

But I don’t think you can ignore him, because he’s too big a force. And I don’t think you can just put the blinders on and just say, “liar, liar, liar, liar, liar” all the time, because people will tune out. So yeah, it’s hard.

The kids who are social media natives will figure this out.

Boomers (whether or not they were once yuppies), Gen Xers like me, and even Millennials, who didn’t have social media when they were little kids, are unlikely to solve the problem of our media failing and how it might be repaired. But the social media natives of Gen Z and Gen Alpha, who grew up on Instagram and Snapchat and TikTok and YouTube, are better equipped to do so.

I found McGrath’s answer to my question of how to fix the media both novel and hopeful. He says:

It’s a really interesting question. I also, I have two Gen Z children…22 and 25, whatever the hell [generation] that makes them anyway. And they, like most people in that generation, are deeply immersed in social media. Like, they’re constantly on their phones. I think, and maybe this ties back into our conversation of a minute ago about is there any solution to any of this? I mean, it could be that this generation is, you know—they’re digital natives, as they’re called, or they’re even social media natives at this point. Maybe they have the solution to some of this stuff about how journalism would look like, in a way that people actually trust what is being reported.

So I guess, this is…me with a glass-half-full hat on, or an optimist hat on: a next generation, because they are so masters of this medium that honestly has thrown someone like me for a loop—I mean, I grew up, you know, on three TV networks and two daily newspapers and that was media—because they don’t know anything other than TikTok and Twitter and YouTube, maybe they understand ways of covering news or communicating things in a better way than I ever can, trying to impose my old sort of paradigm on top of the current age. So that’s one answer to your question.

I spend a lot of time talking particularly to my younger daughter about the way social media in particular has accelerated the trend cycle. And she’s written some college papers about this—that, like, nothing is really a trend anymore for more than like ten minutes, because it spreads so quickly and then there’s a counter-trend to it. And so there aren’t really any trends anymore….

It’s just these little subsets of the culture, these little micro-cultures that exist and...it just constantly sort of feeds through that, in a way that seems exhausting to me, because I’m used to a slower culture. But I don’t know that they, this generation, feels exhausted by it. That’s just sort of the way culture works for them. So maybe that will give them some advantage in sort of understanding the world.

Maybe Gen Z and Gen Alpha will be the anti-yuppies. Let’s hope so.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

Greg Olear talks to Tom about his new book, the Yuppie movement and what it portended to the country, Ronald Reagan and Jack Welch, and nostalgia. In the second half, they talk about how the media is broken, how it might be fixed, and how Gen Z could be just the folks to do so. Plus: media songs!

Follow Tom:

https://x.com/tmcgrathphilly

Buy his book:

https://www.amazon.com/Triumph-Yuppies-America-Eighties-Creation/dp/1538725991

Check out his Substack:

Subscribe to The Five 8:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC0BRnRwe7yDZXIaF-QZfvhA

Check out ROUGH BEAST, Greg’s new book:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0D47CMX17

ROUGH BEAST is now available as an audiobook:

https://www.audible.com/pd/Rough-Beast-Audiobook/B0D8K41S3T

I really believe that the way the media should handle Trump is by ignoring him. When people ask why you don't cover Trump, you tell them that until Trump stops lying, he's not news, he's entertainment. Leave him to the entertainment media.

Of course, their profits will shrink, at least for awhile.

That's the real problem - news media, like many other businesses, used to be interested in serving the public, serving the common good. Now they only exist as one more form of profit extraction.

I got interested in Milkin while watching him lon ago on an NPR interview. Complex character, prostate cancer survivor, donor, etc. I think daily about how the market affects life -- about greed: profits must increase by insane amounts every quarter, consumers' losses multiplying. The growing profits, though, don't accrue to every shareholder equally. Hence index funds, so the little-guy investor has a fighting chance. Beyond that, insider info, institutional-investor advantages, ipos, exec-suite greed sucking up options, etc. Corruption aside, the inescapable fact that, fueled by emotion, the stock market amounts to sanctioned gambling, Milkin is, by far, not the only cause of problems. Capitalism isn't the shiny system beloved by flag-fashion Trumpists. It's become a vehicle for increasing the wealthy's wealth on the backs of struggling consumers, and since there is no end in sight to analyst and market demand for ever-increasing profits, the struggle and inequality can only increase -- which, I guess, is what the book is saying, except Milkin is only one historic cause in a long, growing list. The system is badly broken, currently demonstrated by the number of peope about to vote seriously against their own best economic interests while believing they've found their savior. Now, even the Democrat wealthy are feeling afraid of Biden's wealth tax, etc. They're now racing to join the media in taking advantage of rabid age discrimination by the ignorant on both sides to get rid of Biden.

As for the media, my very varied newsfeed contains about 85% Trump "news" sprinkled lighty with maybe 15% Biden stories. ALL of the Biden pieces are negative, while virtually none of the mainstream Trump articles report in any depth on the dangers, and complaints about media bias appear more justified than ever. I used to belong to a union containing many journalists. If I still had it, I'd hide my membership card in shame -- except I can imagine the pressures from the wealthy owners to favor GOP.