We’d just moved on the first of September. Left our 400-square-foot fifth-floor walk-up on East 7th Street in the East Village—an apartment that cost a staggering $1,800 a month—for a bigger, cheaper, cleaner, safer one-bedroom in Astoria, the part of Queens comprising the westernmost extremity of Long Island, directly across the East River from Yorkville. We didn’t even have cable yet. The guy was coming on Wednesday to install it—Wednesday the 12th.

The day began, as Tuesdays did, with a commute into Midtown Manhattan. I left a few minutes after eight. Stephanie, then my fiancée and now my wife, came with me. She was meeting her friend Kim in the East Village for a morning run. It was an impossibly gorgeous late summer day, mid-70s, low humidity, not a cloud in the perfect blue sky.

The elevated N train was approaching Broadway Station when we turned the corner, so we broke into a jog. We hit the metal stairs at full speed, clanging our way up two flights, and slid our Metrocards through the readers. We burst through the turnstile and onto the train just as the announcement came on: Stand clear of the closing doors. We settled into our seats, laughing, almost giddy.

I left Stephanie at the 49th Street station stop. I strode through Rockefeller Center, weaving my way through the slow-moving, camera-wielding tourists, to 50 Rockefeller Plaza, the global headquarters of The Associated Press, the world’s largest newsgathering agency and my employer.

I didn’t write for AP. I worked in human resources. I was a recruiter. “Staffing Manager” was my official title. I updated the job postings and hired temps and attended job fairs and cracked jokes at the new employee orientation.

When I got off the elevator on the seventh floor, the receptionist hit me with the news: “A plane crashed into the World Trade Center.” Initial reports had the plane as a Cessna, she told me, the kind John Denver was flying when he crashed and died.

“What kind of idiot,” I said, “doesn’t see the World Trade Center coming at him?”

All over the city, people were making the same bad joke.

I went inside, sat at my desk. I drank my coffee, ate my marble pound cake, read the news. Pictures of the damage were available online. A small black hole near the top of the tower, black smoke billowing out, its trail a black scar against the perfect blue sky.

The phone rang: Stephanie. She was frantic. She’d been trying to get through for awhile. “I couldn’t get downtown,” she said. “They stopped the subway at 8th Street.”

The driver, she said, made this announcement, in the same monotone he would use to announce the next station stop: “The N train is not going past 8th Street because a plane crashed into the World Trade Center.” Jaws dropped, she told me, and silence fell upon the riders as they confusedly filed out.

“I want you to leave,” she said. “I want to see you. I want you to meet me at Kim’s.”

I didn’t understand her panic. It was just an accident—an unusual accident, to be sure, but an accident. These things happen. I sipped my coffee. I took another bite of marble pound cake. “I can’t just leave,” I said. “I’m at work.” I told her I loved her and hung up.

And then the second plane hit.

There is nothing special about my story. I didn’t work at the World Trade Center. Neither did Stephanie. We didn’t know anyone who did. Everyone in our little world survived unscathed. And almost everyone in our little world lived in the city, and thus had a similar story, a similar experience—or a much more perilous one. Even our move to Astoria, away from the noxious smoke pouring from Ground Zero, was fortuitously timed. We were unremarkable, two New Yorkers who were fortunate enough not only to survive, but to not know anyone lost in the attacks.

Twenty years later, I realize, things have changed. We now live in the Hudson Valley. Most of the people in our current orbit did not live in New York City on 9/11. From her vantage point outside the 8th Street subway stop, Stephanie had witnessed, with her own eyes, the collapse of one of the towers; there’s nothing unremarkable about that. Furthermore, two decades is a long time. Last month, I was having dinner with some colleagues, and the subject of the 20th anniversary came up. One of my colleagues was in second grade when the towers fell. Another was a baby. When I casually mentioned that I was in Manhattan on 9/11, they seemed to be taken aback.

When September 11 looms on the calendar, I never quite know what to do. Some years I make a point to write something, share something, take time with my memories. Other years I try and ignore it. But on the 20th anniversary, I felt like I had to pay some sort of tribute, do something special. So I asked the comedian, political commentator, and podcaster Noel Casler, a New York guy, to come on my podcast to share memories of 9/11. Just the day itself: what happened to us, what we were doing, what details stuck with us, all of it.

The idea is to preserve the memory. As Zbigniew Herbert commands in his poem “The Envoy of Mr. Cogito,”

go upright among those who are on their knees

among those with their backs turned and those toppled in the dustyou were saved not in order to live

you have little time you must give testimony

Let this be my testimony.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

S2 E3: Tuesday’s Gone: Remembering 9/11, 20 Years Later (with Noel Casler)

Description: Twenty years ago, on an impossibly gorgeous September morning, two hijacked planes crashed into the Twin Towers, the first at 8:46 AM, the second 17 minutes later. Both Greg Olear and his guest, comedian, political commentator and podcaster Noel Casler, lived in NYC in 2001. On this special edition of the PREVAIL podcast, they share their stories and recount their memories of that fateful Tuesday, and the days that followed.

Follow Noel on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/caslernoel

Visit Noel’s website:

https://www.noelcasler.com/

Download Noel’s podcast:

https://www.noelcasler.com/podcast

The Anthony Lane piece I quote in the intro:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2001/09/24/this-is-not-a-movie

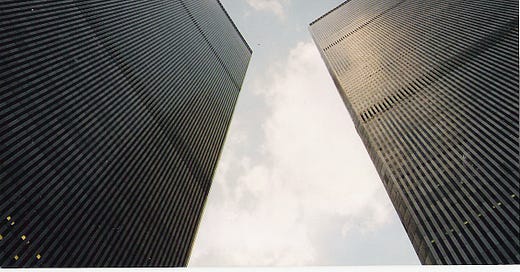

Photo credit: Karl Döringer. Looking up at the World Trade Center, 1995.

Last weekend, I was narrator for "110 Stories" a show written by Sarah Tuft, comprised completely of remembrances of first responders and survivors of 9/11. She was a volunteer at ground zero and as she delivered food and water to the walking wounded, she asked for and received many of their stories. It is being performed in over 70 venues this weekend. For our program, we cast members were asked not for our bios, but for our own stories of that day.

Mine was pretty simple. On that day, the world stood still. Beginning with a jarring phone call out of the blue at 8:00, I literally STOOD in front of the TV all day and watched the hell that was happening in real time. Outside, in my remote area of the Texas hill country, there literally was not a sound. No planes in the air. No cars on the roads. Not even birds in the trees.

Did anyone watch "Memory Box"?

Greg. This took my breath away.

Oh shit. Jerk my heart. I guess everybody has a 9/11 story and maybe someday the best will be collected in an anthology. This one should be included.

The BBC collected some in a book I have now lost. They included a transcript of a 911 call from a young woman trapped in an elevator. “The floor is getting hot!” she exclaimed.

Oh damn. Oh damn damn damn.

Thanks. Greg. This stuff runs deep.