Ukraine Dispatch: The Smell of Izium

After touring the Odesa opera theater during an air raid, Zarina Zabrisky travels to the shelled city of Kharkiv and witnesses the mass graves at Izium.

By Zarina Zabrisky

Odesa, Ukraine

Why Report from Mass Graves?

Reporting from the mass grave site with nearly 500 bodies in the newly liberated Kharkiv region was not an obvious decision.

In 2022, after Russia started the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I became a war correspondent reporting from Odesa, Ukraine—a city where I spent dreamy summers as a child. I was fifteen minutes’ walk from the opera theater I was in love with since I was a kid. It’s the centerpiece of my first novel, and I, quite insolently, consider the sculpture group on the frieze my personal muse. Terpsichore, the theater arts muse, drives a panther-pulled chariot soaring off the edge. Flying into the unknown, furious, fearless, is Ukraine.

Reporting about a wartime opera premiere, I got to sneak around an exquisitely beautiful—if a bit ornate—opera theater all by myself, with not a soul in the marble hallways. The air raids interrupted the dress rehearsal, so while performers played cards in the bomb shelter, I roamed around. Giant wardrobe and set rooms smelled like an old theater, makeup and dust. In the front, I saw myself in the sparkling mirrors, framed in golden lacey blossoms and heavy-bottomed cherubs.

That was easy and delightful stuff. Reporting from a relatively safe city with plenty of buzzing cafes, art exhibits and lovely beaches (mined and closed, but still) and an occasional shelling is not exactly reporting from the front line—or from a mass grave.

If you report something, you should try to cover all aspects. If you cover war, you cover war. It can’t be all opera. Yet the war has so many sides that you can’t possibly cover all of it. Writing news is like being a dog running after a car, barking: you will never catch up—and the next car is just around the corner.

I started to venture out from Odesa, taking local buses to other parts of Ukraine—shelled, bombed, burned. I reported from Bucha, Borodyanka, Chrenihiv villages, the Chornobyl nuclear power plant.

Still, the mass graves made me stop and think. All four of my great-grandparents are buried in mass graves. Two, shot by the Nazis in Ukraine, in Babi Yar. Two, starved to death during the Siege of Leningrad. A mass grave somewhere around there. The Soviets didn’t exactly run DNA tests so we just don’t know. I grew up with the shadows of these ancestors. My grandparents lost their entire families under unthinkable circumstances and while they didn’t speak much about it, it was just there. Did I feel like I owed it to my grandparents?

Kharkiv: Vasyl

20 September 2022

I arrived in Kharkiv in the pouring rain, pulling my big bag off the train with a bulletproof jacket and helmet. At a grim railway station, people in brown and green—military—stood under the awnings of closed and boarded stores, smoking, like at a factory entrance. A Norwegian soldier asked me for a cigarette. Like everyone else at the station, he looked like he hadn’t washed for a while. After sunny and festive Odesa, this square felt more like a war zone. The taxi was too expensive, so I took a tram to my next destination—an interview with a rock musician turned volunteer.

“Where do I pay?” I asked.

“It’s free,” said an old man with a big bag. Everyone on the tram was old and gray, and carried big bags. We all looked like refugees.

As I walked in the rain through empty streets and yards in a Soviet-style neighborhood, an air raid started. High-rises with playgrounds here and there, no shops, no people, no cats or dogs, not even pigeons. My gear bag was getting heavier. I sat on it and had a Zoom staff meeting with one of my newspapers. My editor and publisher both said that I couldn’t call Russian invaders “Russian invaders” because it wasn’t sufficiently impartial.

“We needed to give both sides’ perspective,” they said.

“It’s like representing Hitler’s side in 1942,” I said. “The Russians invaded Ukraine, that’s called ‘invasion.’”

A door squeaked behind me, and an old lady pushing a cart stepped out, squinting at me suspiciously. An explosion nearby shook the ground, but the lady didn’t stir.

The rock musician, Vasyl, spoke Ukrainian and told me about evacuating people under the fire and delivering food to remote villages. Everyone volunteers in Ukraine—doctors, artists, punks. By midday, we drank whiskey in the kitchen, the loud explosions in the background like a restaurant soundtrack.

Vasyl showed me a letter in Russian, in a schoolchild handwriting: “Dear Russian soldier, Remember, the whole country is behind you. Russia always wins…” A big orange Z was painted across the letter.

“They bring shitloads of these to the front,” Vasyl said, “boxes and boxes.”

He showed me a kindergarten next door, bombed just a week before: a large crater in the middle of the playground, shrapnel holes in the walls. No one was around. As we hopped the fence, Vasyl told me that his driver got killed while they were delivering bread together. He smoked and his face didn’t show much emotion.

Kharkiv: Yuri

Yuri, a retired professor and a poet in his 70s, insisted on buying me coffee and a Lviv croissant sandwich. Men in Ukraine, for the most part, would not hear of a woman paying for anything. My attempts to convince him that I was a journalist, and it was a war time, led nowhere. Yuri looked and acted like a perfect British gentleman circa 1913, with impeccable silver moustache and ironed shirt and coat.

He told me that in winter the Russians lived in his cottage house in the outskirts of Kharkiv, where they burned his library—rare and vintage books—in the stove, to keep warm. They burned the full collection of Pushkin, the Russian Shakespeare. His name and poetry are weaponized by the Kremlin to push the idea of the “Russian world:” The great brotherhood of all Russian-speakers around the world, united by the Russian language and tradition. My great-grandparents who froze and starved during the Siege didn’t burn their Pushkin. Yuri’s fingers shook as he told me about the loss.

The explosions outside continued, but no one around paid any attention to them, just like in Odesa no one paid attention to air raids. The girls at the counter made coconut lattes, the customers ate salmon sandwiches and truffle cakes. Outside, people walked their dogs. The bombing continued.

“Why don’t you leave?” I asked Yuri.

“My daughter’s here, she’s helping the military. They come from the frontline to sleep, eat and wash at her place. You know, I can’t forget: I talked to this one young man, an officer, gave him some reading recommendations—he was really interested in psychology, wanted to read Fromm. A month later, he was killed. Why? It doesn’t make any sense.”

I asked Yuri if he, a Ukrainian Jew, experienced any anti-Semitism. Putin claims that the “Ukrainian regime” and Zelensky’s government are neo-Nazi. (Zelensky is a Jew.) In the USSR, Yuri said, that had happened. Not in Ukraine. Not one time.

Unlike Vasyl, Yuri spoke Russian, and I asked if he felt oppressed because of that. He looked at me like I fell from the moon.

“Everyone speaks Russian in Kharkiv. We are still Ukraine. Look.”

Outside the window, Ukrainian flags were beating in the wet wind on every corner. A man in a hoodie with the Ukrainian trident walked next to a woman carrying a bag with a slogan “Russian military ship, go f*ck yourself.”

“True, in the U.S. everyone speaks English, but it doesn’t make the country a part of England,” I said.

A Night Bombing

As I took a trolly to my Airbnb, the distant explosions never stopped. I could see how you got used to them. A man named Oleksii volunteered to help me find my place. I always wear my accreditation card around my neck, with a big PRESS on it, and with my gear bag and a backpack I am clearly a foreigner. Oleksii told me that he ran away from Crimea in 2014—when Russia invaded and annexed that part of Ukraine—and hadn’t seen his family since. With the Ukrainian counteroffensive going well, though, he hoped to see them soon.

“It will be all good. We’ll get Crimea back.”

Faced with the worst calamities—the loss of homes, of loved ones—Ukrainians manage to stay hopeful, even positive. They start rebuilding while still being bombed.

I finally found my building but not the entrance. A sign was missing. Some windows were shattered. I called the manager and she explained that the sign fell down, hit by a shock wave. The door was open, and the heat radiators fell off their hooks; more shattered windows. I climbed to the top floor. A part of it had no roof or walls and the wind and rain whistled through it. The other side of the floor turned out to be a perfect, Scandinavian-design mini-apartment complex: my room could be easily in Holland or Germany. Everything was sparkling clean, the air-conditioner worked, the shower was—yes!—hot. Out of the window I saw broken and boarded windows, wide and empty streets, and, as the night fell on Kharkiv, the lights did not turn on. In an hour, the second biggest city in Ukraine was consumed by complete darkness.

I drank some cognac and fell asleep, only to be awakened by a fantastically loud explosion nearby. The walls were shaking, my bed was shaking. Another one. Another. It kept going and I thought, through my sleep, that I should put on my pajamas. What if they hit here and… I didn’t have my pajamas on? Nor did the building have a bomb shelter. I fell back asleep to boom, boom, boom…

As I walked down the stairs to meet Vasyl, I saw the smoke rising close by through the sharp shards of the broken windows. A local Telegram channel reported that a residential building was hit, people were still under the rubble. I wrote about these explosions in my daily reports; I would be writing about this one.

300,000 Russian stiffs

21 September 2022

I pull out of Kharkiv with Vasyl, Sasha, a boxer and a formidable man with a broken nose and fists the size of my head, drives the minivan through destroyed villages, navigating smashed and burned cars by the side of the road, gently and carefully. Vasyl spoke Ukrainian, Sasha spoke Russian, I spoke something in between. An orange car with a Russian swastika, Z, written all around it, looked like a croissant sandwich I had the day before. Gloomy men with AKs checked our documents at every block-post.

At the Izium check point, 125 kilometers from Kharkiv, we hit a dead end. No journalists were allowed, no information was given, and there was no cell service. Many journalists were outside, smoking, poking on their dead phones by the side of the road. Loud explosions boomed in the forest behind the block-post, much louder than in town.

We drove around trying to find a signal, and finally got one by an empty bus stop. Vasyl and Sasha were calling military and police people to get permission to get to Izium. I checked Telegram: Putin had just announced a “partial mobilization” in Russia. Three hundred thousand soldiers were to be forcefully recruited. He also threatened to use nuclear weapons.

“Guys, a partial mobilization in Russia—”

A Ukrainian soldier with an AK knocked on the window.

“Hey, we are just looking for connection. They won’t let us into Izium, bro,” said Sasha.

“You made us nervous,” said the soldier in Russian, and peeked inside the minivan, waving the gun. “What do you have inside?”

I smiled at him and showed my accreditation. I always groom myself for any trip after I was reprimanded at a checkpoint in Mykolaiv for looking fine on my accreditation photo but looking like crap there and then. The fact that we just spent three hours in a bomb shelter after climbing the ruins of several buildings didn’t make any impression—“wear lipstick, brush your hair” was indispensable advice that I took to heart.

“Hey, you are hiding a pretty woman there!” said the soldier. “Didn’t get to Izium? I’ll give you a tour! You want to see some Russian stiffs?”

“Thanks. I—"

“Oh come on, you are a journalist. You can write so someone takes them away. They are just stinking up our checkpoint. You’re a war correspondent.”

It was true. I was about to see mass graves, right? That would be an initiation, I thought.

I got out of the minivan. We walked past a burned car and into the field. On the right, I saw abandoned Russian fortifications—just some pits in the ground and garbage in a little forest. In front of us was another burned car.

I took my phone out and put it in between my eyes and the objects I was about to see. We walked around. Two corpses, spread on the grass, in a shavasana pose, were not scary. More of a nuisance. Their boots were lined up and pointing into the sky—as if they were still standing in line. I snapped photos. Vasyl took a selfie with the corpses. I thought of his driver-friend who was killed.

“Tell someone to remove them, we don’t want them here. You know how many are in the fields? The Russians leave their dead behind ‘cause they don’t want to pay reimbursement to the families. We don’t want them either. And you know how many are still roaming in the woods? They left their own behind. So they hide there and shoot from time to time, we shoot back. They have no food, probably eating mushrooms or hunting. Hey, do you want to shoot my gun? At the road sign?”

I took his AK and shot at the road sign, thinking of 300,000 Russians to be mobilized forcefully, and Putin. We were not supposed to shoot but it was just one bullet and it felt really good.

“Good, eh? Shooting is good but not at people. I just want to go home, to my wife. Crawl in bed, hug my wife and sleep. I’ve been at war since 2014.”

I thanked him for his service, and climbed into the van. We didn’t get to see the mass graves or Izium that day. I went back to the Scandinavian room and wrote a report for the day: Putin, mobilization, explosions in Kharkiv.

“I’m lucky—they only tortured me twice”

22 September 2022

The next day, I still couldn’t get into Izium. I used all my connections but it was a no-go. The police were there, something was going on, and that was it. I wrote my daily report and then Sasha came and drove me to South Saltivka, the place that was ruined the worst by the Russians, an apocalyptic vision—churned, burned, ruined high-rises, street after street, walls that slid down, baring rooms as they were—a desk, a lamp, a lace curtain flipping in the wind, a dead plant. I have seen this before in Borodyanka by Kyiv and in Serhiivka by Odesa but never got used to it. Holding a camera between my eyes and the horrible sight helped, as usual.

I record it for history. I report it. I see it but I don’t see it—although I do see it.

I then interviewed Oleksandr, a man the Russians tortured for nine days, in a basement in the occupied territories. He was there on a business trip the day the war started and didn’t happen to have his passport with him. The Russians suspected him—and everyone else in that basement—of gathering information for Ukrainian army, on where to fire.

A Russian officer gave orders to a soldier to put wires to Oleksandr’s hands, and they then used electric shock to force the confession.

“I’m lucky,” said Oleksandr. “I only stayed there for nine days, and got electroshocked twice. Many stayed for months and got it much worse. I am a lucky person.”

After he got out of the basement, he lived under the occupation for six months—no running water, electricity, heat, or communication. The Russians mined the well that he and his neighbors used to get water.

“I’ll never do BBQ again. I can cook anything on fire now.”

“How do you feel about the Russians?” I asked.

“There are two types. First, there are Russian people—and they don’t necessarily live in Russia, they are all over the world, in Ukraine, as well, and some suffered more than I did. And then, there are Russian world citizens—those are fascists, poisoned by their ideology. Those I wish all the worst.”

I asked him if he was going to see a psychologist.

“If I start going nuts, I will. I’m fine now. I need to take care of my mom for now.”

Back at my room, I looked out of the window. The sky was flaming red. A golden cupola of a church was shining. On the other side of the glass sat a green grasshopper, a big one, more like a locust, with one hind foot only. It was holding on the glass and I took two photos: in one, I zoomed in and the insect was oversized, taking over the sky and the building behind it—an invader. In the other photo, I changed focus and it was the city in all its baroque Soviet grandeur, with the invader diminished, almost invisible, just a bug. I felt sorry for the locust left behind on the cold glass.

Izium: “The Russians just followed the order”

23 September 2022

The next morning, I finally got a chance to go to Izium with a press bus. At 6 am, I called every taxi number I could find—no answer. I looked for a bus—no bus. I put my bulletproof vest with a big PRESS sign on, and trotted along the wide street, following my GPS, in the rain. The bus was leaving soon, and I had 24 minutes to make it. I run fast but the bulletproof vest was heavy. Somewhere midway, a charter bus transporting workers to some factory stopped: the driver took pity on me and gave me a ride.

“Where are you going?” asked the lady next to me.

“To Izium. I am a reporter.”

She reached into her bag and offered me a handful of hard candies.

At 7 am, the bus, escorted by police cars with sirens, rushed to Izium. It was pouring again, really hard. I kept my vest on to stay warm.

We arrived to a school, bombed, burned and being repaired. Grandma Zoya, an ancient lady in a purple headscarf, told me in Ukrainian that she, her kids, grandkids and great-grandkids, had all studied at this school. Her eyes were transparent-blue, tears trembling, but never falling. Her son and a twelve-year-old granddaughter were wounded by the Russian shells, at their own home.

“War is a hard business, honey,” she said.

A fourteen-year-old, Roman, had tears in his eyes, too. “It was my school. We don’t have a school here in Izium anymore. I saw two neighbors with their heads severed.”

“How did the Russians treat you?”

“Oh they were all right. Just ordinary people. They didn’t do anything bad to me, just followed the orders.”

I walked around the neighborhood, keeping on the path because the area all around was mined. The explosions I heard now were just sappers de-mining the streets, buildings, and fields. The Russians left mines everywhere after fleeing. They did it in Hostomel, Irpin, and Bucha as well. I saw a pit, a part of the Russian fortification, filled with dirty green, empty wine bottles and took a picture from afar. Two friendly doggies followed me, one jumped on me, wagging her tail. The other one was shaking each time there was an explosion. We all were soaking wet at this point, me and the dogs, and I liked their warm smell.

Mass graves

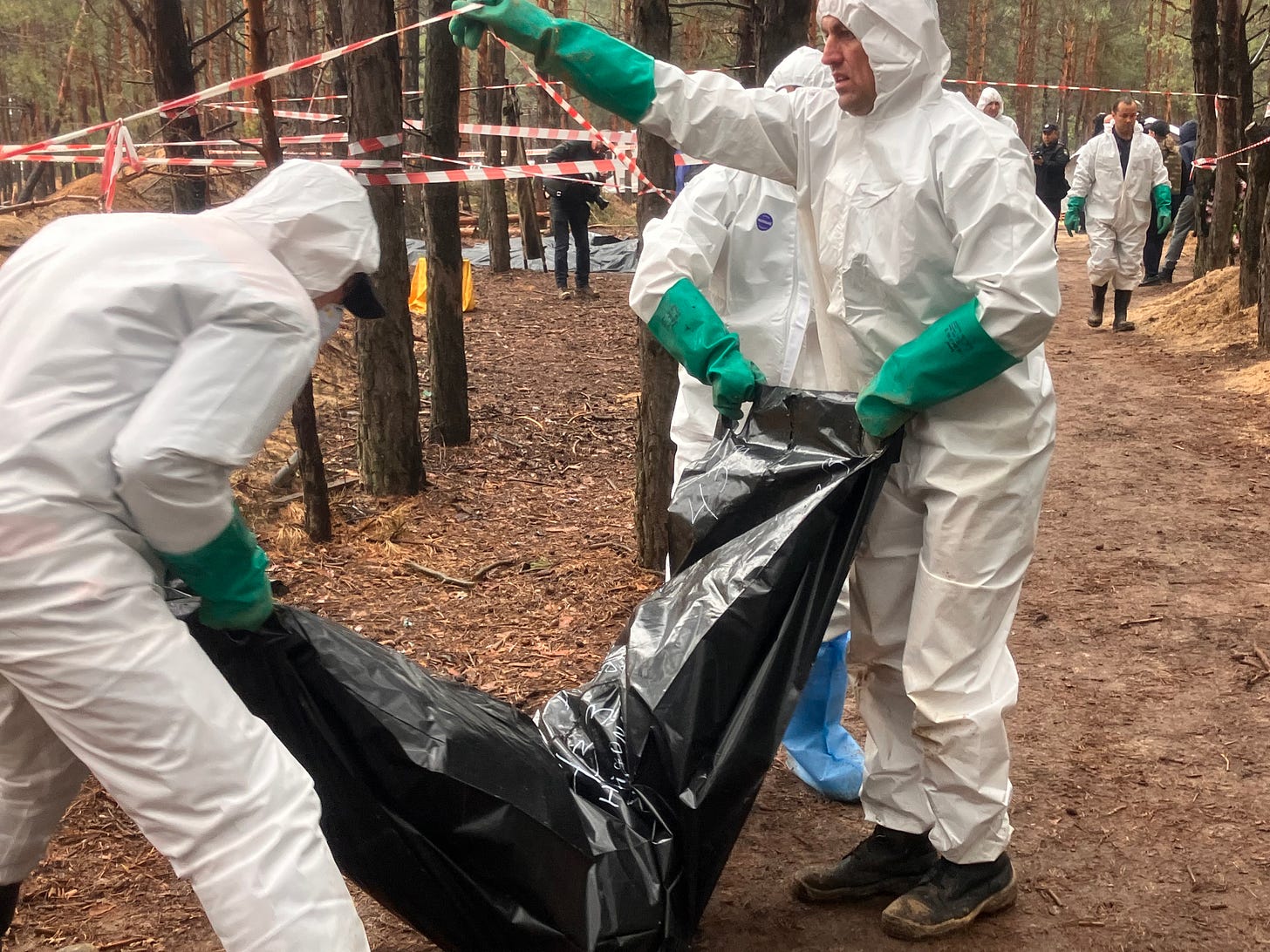

The bus pulled in front of the mass grave site, a fine pine tree forest, and we walked down an unpaved road, drowning in mud. A meat truck with a refrigerator parked in front of the forest had a sign “200” in the window. “200” is a code for corpses.

We entered the forest. I saw people digging, carrying big black bags, smoking, walking. It was very busy and I started to feel the smell that took over me, slowing everything down, shutting down my brain, like there was no time. There I was, walking, taking photos and videos, talking to other journalists, yet everything was a slow, weird movie, happening now and then, with all the strings of meaning detached…

People in white and green transparent plastic coveralls dig yellow soil in the rain. I put the camera between me and the pits in the sand. Snap.

It is so quiet that I can hear a grave digger cough. Four of them remove a wooden cross with a number 412 penciled on it, and start shoveling the earth. They work in unison, in harmony, a well-oiled machine. The yellow sand is flying in the air. Soon one of the diggers jumps inside the grave. I can’t see what he is doing there. Snap.

All four pull a dead body in a black plastic bag out, using a long, leathery belt. Snap.

A woman in a pink transparent rain jacket lifts a stiff hand. Snap. I put my phone between me and the dead body. I still see it. It didn’t look real, more like a plastic corpse at a Halloween store or in a Hollywood horror film. Empty eye sockets, pasty color, the same as the sand, like sawdust. I am nearsighted and even with my glasses on I don’t see well—I am glad that I don’t. Snap.

What would I do with the footage? Will my TV show run it? Invaders are not invaders.

The woman in pink keeps examining the body, methodically, like a robot. Somebody writes down what she is saying, or maybe she is using a Dictaphone.

I hear distinctly, in Ukrainian, “A male. One black sock.”

Another sock is missing. I don’t have it in me to snap a photo.

The group of four men in white keeps digging bodies out. Once the woman in pink is done with her job, the men in white put the bodies in black plastic bags and carry them out to a small lawn between the pine trees and put them next to each other. Little puddles gather on the black plastic. It’s so quiet I can hear the raindrops drumming on the bag.

A priest in black and yellow garb is humming a sermon and waves an incensory over the bodies.

“How could you keep your faith, seeing this?” I ask.

“Jesus Christ didn’t lose his faith on the cross.”

The men in white carry another body past us. I find his answer irrelevant, but the sweet smoke from his incensory is stronger than the stench of the dead. I just want to stand next to him longer to not feel the horror of a smell.

“Is it possible to forgive those who did it?” I ask, pointing at a child’s body.

The bag is much smaller, the raindrops send circles over the puddle in a crevice. The priest says something about the impossibility of peace without forgiveness, but notes that peace should come on certain terms. It really doesn’t make sense, but the heavy church smell feels so good. Nothing is more unbearable than the smell of dead human flesh—even seeing the decomposed corpses is fine. It’s not fine. None of it is fine. This just can’t be happening, but I am here, I see it. I smell it.

I push a wet orange slice into my nose. I brought them with me as advised by a friend. Bullshit, the oranges don’t help. I make a mask out of a scarf. It helps a little. The men in white and green and women in pink smoke a lot, and I can see why.

That smell and the monotonous work—dig, body out, exam, bag, out, next—makes me float and lose time. Authorities came, European diplomats came, a press conference is held over the bodies. I hear, through the cloud of smell. How can the smell mix with sight and sound, it is like a fog: 447 bodies, five children, signs of violent death, evidence of torture. I catch a translation error: after a brief pause, the interpreter omits the castration part. I listen, record, walk more in the mud, record more of the seemingly endless job. With every whiff of wind, the new wave of sweet, rich odor penetrates my skin, it goes into my nose, throat, brain. I can’t think straight. I just want the smell to stop.

The smell

24 September 2022

Back by the bus, I ask a policeman for a cigarette. I hadn’t smoked for about ten years, and before than for another ten. I smell my fingers and, for a moment, the smell stops. Then, it starts again.

In the bus, the driver offers chocolate cookies to me and a photographer next to me—not to eat, to smell. It doesn’t help.

Nothing helps to get rid of the smell. Sweet, sticky, viscous, nauseating beyond any words. The whole bus stinks.

By the time I make it to Kharkiv, I am ready to peel off my clothes, my hair, my skin, to get rid of the smell. I throw everything that was with me in a washer. Even my helmet and bulletproof vest covers. I scrub the steel plates and helmet with dishwasher soap. It doesn’t stop.

The smell follows me everywhere, all the way to a village only seven kilometers from the Russian border, the next day, as Sasha and I walk around the torture chamber, listen to a Ukrainian man who was tortured there, in the railway station turned another torture room, the floor covered with broken glass and letters from the Russian children to Russian soldiers—letter Z on the letters, on the walls, everywhere. Dear soldier, I don’t know you but I believe in you. Russia is behind you.

I smell it through the burned smell of the crater left by a missile, a crater so big that the whole car sits into it, upside down.

I smell it on the train to Odesa. I want to get rid of the smell of the war and I want the war to stop just the way this train is about to stop now at Odesa railway station but I still smell it in Odesa as I stand outside of my building and my neighborhood gets hit by a kamikaze drone.

I wash everything again, two times, and air all that I have outside my attic window, looking at the rusty roofs and lazy Odesa cats sleeping in the Indian summer sun. I start feeling myself again and I am back, close to my Muse, my wild panthers, ready to jump—and I can try and save them by writing about them, by showing their exquisite, fragile, excruciating beauty to the world.

And then, I smell it next day as my editor tells me that what I have seen in Kharkiv and Izium is not urgent or important, and cancels this week’s show. I smell it as quit. Invasion is invasion, and what I have seen is urgent and important and needs to be seen and heard by the world. I will run this footage to history, and I know that the audience won’t feel the smell, and I am glad, I am glad.

Zarina’s work appears in the Byline Times and the Euromaidan Press. Follow her on Twitter.

Photos by Zarina Zabrisky.

No words. Just gratitude that someone so finely tuned to history, nuance and the power and dread of the given moment took on the work of describing this. Horror is a weak word but we use what we have. I offer my thanks and blessing.

No words. Shared.