In November, Anno Domini 1623—four hundred years ago this fall—the poet and preacher John Donne fell deathly ill. He was 51 years old: my age now, give or take a few months (we were both born in ‘72).

At the time, London, where he lived, was a veritable Petri dish of pathogens, so it is impossible to say with certainty which specific malady befell him. Typhus was the culprit, probably, but for all we know, some proto-coronavirus, covid-(16)19, was the microscopic author of his suffering. For weeks, in those dark days before vaccines and thermometers and Tylenol, the poor guy languished in bed, miserable, consumed by fever.

Donne was no stranger to death. His father, a wealthy Welsh ironmonger, died when he was four. His mother, a Catholic, was long dead; her great-uncle was Sir Thomas More, famously executed for treason for refusing to put up with gross Henry VIII’s bullshit. His younger brother, Henry, died of plague in Newgate Prison in 1593; he was there for the crime of harboring a priest. His beloved wife, whom he married secretly and at great personal risk, died in childbirth five years earlier. Donne thought he was done for. And, being a writer—by then, an author of sermons rather than poems; sermons whose audience often included the king himself—he demanded pen and paper, so he could immortalize his fever dreams.

The result was Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, and severall steps in my Sicknes [sic], a 70,000-word collection of meditations, expostulations, and prayers on the subject of sickness and death. Donne polished it off by December. That means that in the space of a single month, John Donne banged out a novel-length opus, while he was shivering in the sheets with a high fever. Devotions upon Emergent Occasions was the product of the first ever NaNoWriMo, and it will never be equaled, let alone topped.

He begins his lament much like a guy would today who goes around everywhere with an N-95 mask but catches the Rona anyway:

Variable, and therefore miserable condition of man! this minute I was well, and am ill, this minute. I am surprised with a sudden change, and alteration to worse, and can impute it to no cause, nor call it by any name. We study health, and we deliberate upon our meats, and drink, and air, and exercises, and we hew and we polish every stone that goes to that building; and so our health is a long and a regular work: but in a minute a cannon batters all, overthrows all, demolishes all; a sickness unprevented for all our diligence, unsuspected for all our curiosity; nay, undeserved, if we consider only disorder, summons us, seizes us, possesses us, destroys us in an instant.

Being the pious, solemn, Old Testament type, Donne believes his malady is the result of sin:

O miserable condition of man! which was not imprinted by God, who, as he is immortal himself, had put a coal, a beam of immortality into us, which we might have blown into a flame, but blew it out by our first sin; we beggared ourselves by hearkening after false riches, and infatuated ourselves by hearkening after false knowledge. So that now, we do not only die, but die upon the rack, die by the torment of sickness. . . .

Personally, I don’t hold with the God-brought-the-plague-to-punish-the-sinners narrative—although I must confess that when Trump got covid, the thought did cross my mind.

The famous passage from Donne’s Devotions is from Meditation XVII. It opens with a Latin epigraph, Nunc lento sonitu dicunt, morieris, which translates to Now, this bell tolling softly for another, says to me: Thou must die. The rest is one big, thick paragraph that begins:

Perchance he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill, as that he knows not it tolls for him; and perchance I may think myself so much better than I am, as that they who are about me, and see my state, may have caused it to toll for me, and I know not that.

In his misery, in other words, he hears the church bell tolling, which he takes to mean the announcement of a death in the congregation. Is he so infirm that he is already dead and doesn’t realize it? Is his death the one being announced? After some lines about baptism, Donne continues with a gorgeous metaphor of all humanity being part of the same big book:

And when [we bury] a man, that action concerns me: all mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated; God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God’s hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another.

Dig the double meaning of “scattered leaves!” Damn, that’s good writing. And this MFer is banging this out with a temperature of 102; when I was at peak covid, I could barely string a sentence together or organize a coherent thought.

Then Donne returns again to the bell tolling, musing on the significance of the bell when he was at the seminary:

As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all; but how much more me, who am brought so near the door by this sickness. There was a contention as far as a suit (in which both piety and dignity, religion and estimation, were mingled), which of the religious orders should ring to prayers first in the morning; and it was determined, that they should ring first that rose earliest. If we understand aright the dignity of this bell that tolls for our evening prayer, we would be glad to make it ours by rising early, in that application, that it might be ours as well as his, whose indeed it is. The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth; and though it intermit again, yet from that minute that that occasion wrought upon him, he is united to God.

“Intermit” means “discontinue.” The bell is not a siren screeching. It is an occasional sound, a summoning, reminding him of his place among his community of fellow travelers on this hostile planet.

Donne’s poetry fell out of favor just a few decades after his death. He was ignored for centuries after that. His work was rediscovered in the late 19th century and only entered the popular culture after the Great War, when the poets William Butler Yeats and T.S. Eliot championed his verse, and—critically—when Ernest Hemingway purloined one of Donne’s lines for the title of his longest novel. This is the excerpt everyone knows. It is sometimes presented as a poem, but while it is poetical, it was written as prose:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

This passage is all the more remarkable because, as Donne suffered in torment, sweating through the bedsheets, too sick to do anything but listen for the tolling of the church bell, he must have felt like he was an island: lonely, forgotten, doomed. His faith in God, and his faith in humanity, allowed him to transcend those adverse feelings and achieve peace of mind, by recognizing that he was part of something greater. Maybe writing it down helped. Maybe he spoke it into existence. At any rate, he survived, and lived another seven years.

Many subsequent poets and lyricists have pushed back on the idea of no man being an island. Matthew Arnold’s 1852 poem “To Marguerite,” for example, opens with a straight-up rebuttal:

Yes! in the sea of life enisled,

With echoing straits between us thrown,

Dotting the shoreless watery wild,

We mortal millions live alone.

The islands feel the enclasping flow,

And then their endless bounds they know.

More recently, The Police hit “Message in a Bottle,” written by Sting, echoes Arnold:

Walked out this morning, I don’t believe what I saw:

Hundred billion bottles washed up on the shore.

Seems I’m not alone at being alone.

Hundred billion castaways, looking for a home.

Not “no man is an island;” rather, all men are islands.

And Paul Simon could not be more explicit: “I am a rock, I am an island.”

The pushback is clever, but it feels teen-angsty and immature.1 For me, Donne’s key line is this: “any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind.” (I love that word choice: involved.) We feel this acutely, when we watch footage of Russian missiles obliterating apartment buildings in Ukraine, or Memphis police officers brutally beating an innocent man to death at a traffic stop. It is why we want to stop watching the news, and also why we don’t stop watching. Our empathy makes us want to avert our eyes, just as it compels us to keep them open. This overloads the system (which the Steve Bannons of the world well know and weaponize for their malefic purposes). If we are not involved in mankind, why would we care?

Lately, it seems, the bells have been tolling non-stop; the tintinnabulation is deafening; our own lamentations are drowned out by the reverberating clang. But this is the cost of being “involved in mankind” in the Internet age, when no one with WiFi is an island.

Between social media and the pandemic, it has never been easier to understand that we are all the same, that what affects one of us affects all of us. Bannon and Tucker Carlson and the other bad guys—Donne would see them as agents of Satan, probably—seek to amplify our petty differences. Why? Because they know that the things that unite us are so powerful and so inevitable.

ICYMI

Our guest on the Season 2 Finale of The Five 8 was the inimitable Pete Strzok:

We are off next week—although there may be a surprise on Friday for our members—and will kick off Season 3 on February 10.

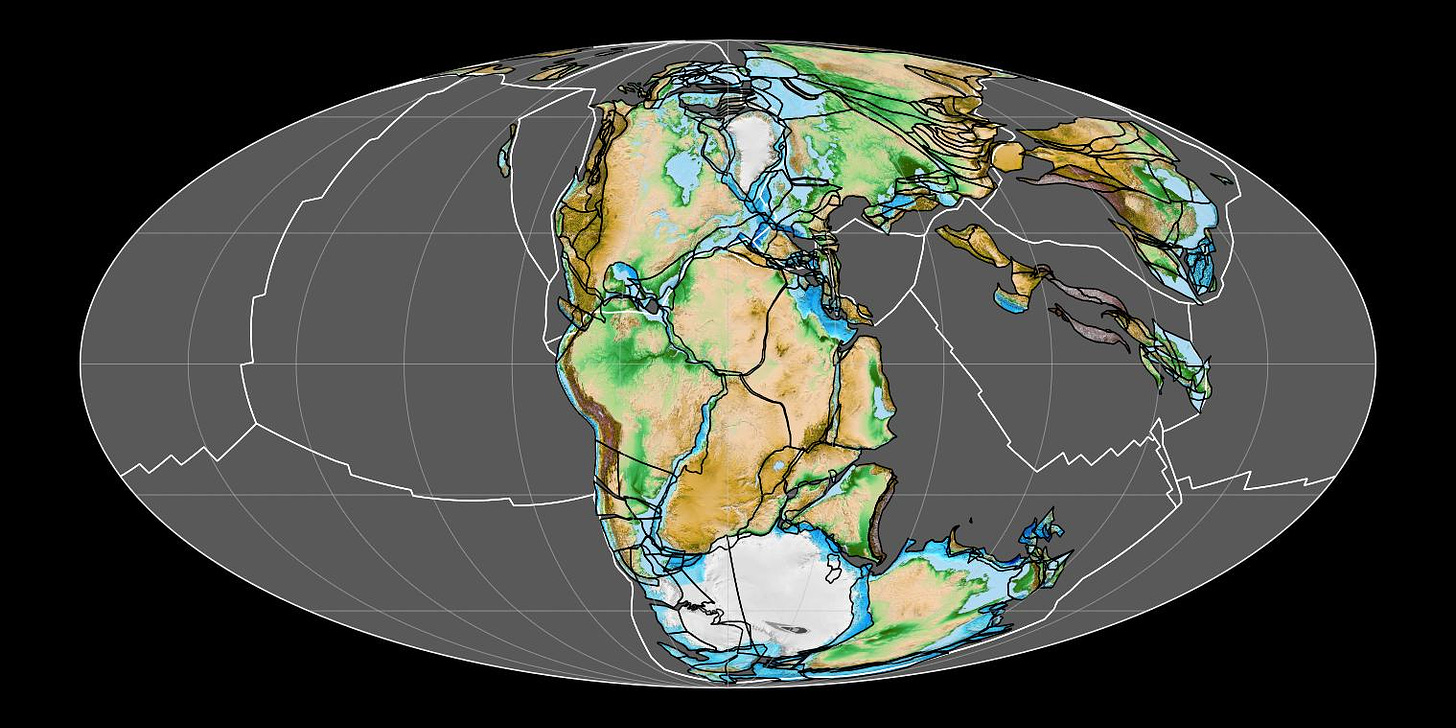

Photo credit: Fama Clamosa. Pangaea.

Working at CVS in high school, my friend Mike H. and I were talking about this. I said, “No man is an island,” and Mike said, “No, but some are endcaps.” We thought this was the funniest thing ever.

What a wonderful way to start today— a cup of Java Blue, a history lesson, incredible references with perspectives to connect with our world… Bravo!

Four hundred years ago! Who would have thought back then, there would be many similarities to life now? Only a dedicated, knowledgeable, ambitious and very good writer could wind this web. It’s so good. I do not have a writer’s mind, but I like to think about how the idea about writing this, came to you. Was it the connection to John Donne’s age? Covid? For Whom the Bell Tolls? (Which I have not read, but might now!). Or, coming upon the word tintinnabulation…Hmmm. What can I write about to incorporate this amazing word? The word I continue to hold near and dear is HOPE. LB and you as well as many many others are helping to expose the “agents of Satan”. I do believe Justice is coming. Thank you for continuing to be “involved in mankind”.