Dear Reader,

Wilfred Owen is categorized as a war poet, although his poems, written on the front of the Great War that would claim his life, stand in vehement opposition to armed conflict. Strictly speaking, he was a peace poet.

Not long after his deployment in June of 1916, he was knocked out by a mortar shell blast, and subsequently sent to Craiglockhart, a military hospital in Edinburgh, to recover. There he met his fellow poet, Siegfried Sassoon, whose influence turned Owen away from derivative imitations of classical poetry to the gritty, personal style for which he is known. “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” a title suggested by Sassoon—and which sounds like it should be a Green Day song or a lost Nirvana album—was composed at this time.

Owen’s finest poem, “Dulce et Decorum Est,” is a rough read, rich in unpleasant detail, leaving little to the imagination. It is a poetical response to the Roman lyric poet Horace, with whose work Owen was familiar—everyone back then studied Latin in school, because, I guess, that’s how people alleviated boredom before TV or video games or comic books or Top 40 radio or arguing with randos on social media—and to whose Odes Owen alludes in the closing lines.

In the first two stanzas of the poem, Owen describes the horrors of watching one of his comrades die miserably by poison gas. (I’m not going to post that part here; it’s too grim for Sunday morning, and this week has been grim enough.) Then, a short stanza:

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

The poem ends like this:

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

This is powerful, powerful stuff, as powerful in its way as the weapons of war that were its inspiration. The provocative word choices—smothering, writhing, gargling, froth-corrupted, incurable—cut right through the bullshit. Basically, Horace was like, “War is glorious!” And Owen was all, “No way, Boomer.”

The Latin lines, footnotes everywhere insist, roughly translate to “It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.” Patria is country, mori is to die. But I know enough Latin-based English words to question sweet for dulce in this sense, and how exactly does decorum equate to fitting? Shouldn’t it mean proper?

Unfamiliar with Horace—not being taught Latin declensions was a failure of my education—I went back to the source material. The allusion comes from the fourth stanza of Ode III.2:

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori:

mors et fugacem persequitur virum

nec parcit inbellis iuventae

poplitibus timidove tergo.

Which really clears things up. Google translates this as “It is sweet and fair to die for one’s country: death pursues the fleeing man, and does not spare the unwarlike youth, the cowardly rear.” This is not far off from Christopher Smart’s clunky, inelegant 1756 prose translation: “It is sweet and glorious to die for one’s country; death even pursues the man that flies from him; nor does he spare the trembling knees of effeminate youth, nor the coward back.”

John Conington takes a few liberties in his 1882 stab at it, imposing strict meter and rhyme not found in the original:

What joy, for fatherland to die!

Death’s darts e’en flying feet o’ertake,

Nor spare a recreant chivalry,

A back that cowers, or loins that quake.

But this feels too flowery, too forced—like something Jon Lovitz would have mocked in his “Master Thespian” sketches on SNL.

Looking up each Latin word individually, we come closer, I submit, to what Horace is getting at. One of the challenges of Latin is that the subjects, verbs, objects, and adjectives aren’t in the same place as they are in English. Everything is jumbled and messy—and in Latin poetry, even more so. If we invert the lines a bit, the passage makes a lot more sense. This, I think, is closer to what he’s actually trying to say here:

We can’t outrun death, no matter how hard we try.

Death catches up in the end, to the brave and cowardly alike.

We all die regardless of how we act or what we do; therefore,

It is both honorable and prudent to die for one’s native land.

This is more pragmatic and less rah-rah—although it remains shitty advice.

Horace is undoubtedly one of the most important poets to ever put quill to parchment. Everyone from Ovid and Boethius, from Milton to Keats, and from Auden to Robert Frost fell under his far-reaching influence. While I own that I’m hardly an expert, not being up on the Odes and the Satires and the Ars Poetica, what little Horace I’ve read strikes me as pompous, self-important, and excruciatingly mansplain-y. What’s the Latin word for meh? I hold with Byron, who wrote:

Then farewell, Horace, whom I hated so

Not for thy faults, but mine; it is a curse

To understand, not feel thy lyric flow,

To comprehend, but never love thy verse.

Maybe Byron should have trusted his instincts? Smart, incidentally, gives Ode III.2 the subtitle “On the Degeneracy of the Roman Youth.” This is the first-century-BCE equivalent of “You kids get off my lawn!”

In real life, Quintus Horatius Flaccus wasn’t exactly the model of battlefield valor. As he recalls in Ode II.7: “Together with [my buddy Pompeius Varus] did I experience the [Battle of] Philippi and a precipitate flight, having shamefully enough left my shield; when valor was broken, and the most daring smote the squalid earth with their faces.” So when he writes about the cowardly man turning tail and fleeing—or “the trembling knees of effeminate youth,” if you prefer—he speaks from personal experience.

At Philippi, fought in October of 42 BCE, the despotic duo of Octavian and Mark Antony make short work of Brutus and Cassius; it is the beginning of the end of the Roman Republic. Horace was fighting with the latter—that is, against the soon-to-be imperial forces. Afterwards, Octavian offers him amnesty, which Horace accepts. Octavian becomes Caesar Augustus, and the wide-eyed lyricist fighting for the Republic becomes, basically, the poet laureate for the nascent Empire—Great Caesar’s great ass-kisser.

Odes II was written some 20 years after Philippi, around the time Octavian adopted his twin titles, but before Caesar Augustus became sole ruler of Rome. “Dulce et Decorum Est” came out 1,950 years later. So Horace was writing at the beginning of Rome’s imperial power; Owen, at the end of Britain’s. (Britain—itself once a Roman colony.) One empire waxes, the other one wanes. How does this historical context inform ode and poem?

In the United States in the third decade of the 21st century, we have a taste of both sides of this political transformation. U.S. global hegemony has been in decline at least since 9/11, and arguably for decades before that. Meanwhile, the slow but inexorable rise of American fascism has brought chaos and division to the country—a period of tumult not that unlike what Horace lived through two millennia ago. Perhaps this is why men spend so much time thinking about the Roman Empire?

After his hospital stay, Sassoon refused to return to the field of battle. Somehow avoiding a court martial, he wound up in England, training those British troops who would go off to fight and die in the last year of the war. He survived to live a long, full, interesting life as a well-respected man of letters.1

Wilfred Owen was not so lucky. Unlike Sassoon, he insisted he return to the front; he felt it was his duty to report on what he saw there—a war correspondent working in verse. He died in action, crossing a canal in northern France, on November 4, 1918—almost exactly—to the minute!—one week before the armistice ended the war. His mother, to whom he posted all his poems, was informed of his death on Armistice Day. That’s an irony that would have titillated Horace.

Technically, Owen died for his country. But he really died for something greater: his sense of duty to report on the horrors he saw—and, also, for his poetry.

Was that sweet? Was it fitting?

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Tony Michaels, host of “The Tony Michaels Podcast:”

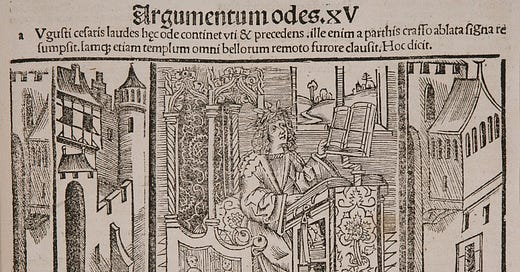

Photo credit: Horaz beim Studium. Holzschnitte, aus: Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Opera, Straßburg: Johann Grüninger, 1498. Gutenberg-Museum Mainz, Stb Ink 888.

Michael Wormser writes to correct my error on the details of Sassoon’s war service: “One minor issue: Sassoon did return to the Western Front after Craiglockart. He thought it was his duty to return to his unit and succor his men. Unlike Owen, Sassoon was already an established poet and war hero by 1916 and was loved by the men who served under him. He was wounded again after his return to the front, a head wound from, I think it has been confirmed, friendly fire. So, he again was hospitalized; this time near London.”

Wow. Always hated Horace (and, like Byron, thought it my fault). Has there ever been a good "state" poet? Maybe Frost, who at least kept it ambiguous.

Here's Shakespeare's gloss (put in the ironic mouth of Julius Caesar):

“Cowards die many times before their deaths;

The valiant never taste of death but once.

Of all the wonders that I yet have heard,

It seems to me most strange that men should fear;

Seeing that death, a necessary end,

Will come when it will come.” (Indeed)

Which I've always thought pretty good advice, especially when darting across four lanes of speeding traffic.

As a stoic, I vibe with Horace. In an important way, Wilfred Owen did, too; insofar as he gave his life for something greater than his personal self. Let's be grateful that, unlike Sassoon, Owen went back to the front to produce 'Dulce et Decorum Est'. Art *matters*