Dear Reader,

Plenty of music snobs, including many rock critics, regard “Stairway to Heaven” as a childish attachment—a cute little ditty we enjoyed in our adolescent ignorance because we didn’t know any better. Lester Bangs is one of those people. Erik Davis, who wrote the (wonderful) 33 1/3 book on Led Zeppelin’s untitled fourth album,1 is one of those people. Heck, Robert Plant is one of those people. In interviews with him on the subject, the Zeppelin front man comes off a bit like William Shatner addressing the gathering of Vulcan-eared Trekkies in that classic SNL sketch: “You turned an enjoyable job I did as a lark for a few years into a colossal waste of time!”

I call bullshit. I think the “Stairway” hate is performative. I think music snobs are terrified that if they cop to liking a song everyone else likes, including the tasteless clods who also dig cheesy schlock like Bon Jovi and Poison, they will somehow lose their cred.

To me, “Stairway to Heaven” is an unequivocal masterpiece, and I love it without irony or qualification. I love the hauntingly beautiful, minor-ninth-infused opening acoustic guitar part; that it was supposedly lifted from Spirit’s “Taurus” doesn’t bother me any more than the plot of Romeo and Juliet being appropriated from a cheesy Arthur Brooke play (although it does give new meaning to “My Spirit is crying for leaving.”) I love the way the song builds and doesn’t hew to the usual verse-chorus-verse-chorus formula. I love the way Bonzo’s drums come in when they do. I love the bustle in the hedgerow. And I love that it conjures up memories of high school dances and Battles of the Bands and adolescent wanting and the glory of teenage night.

Yesterday, inspired by a tweet, I watched a clip of the 2012 Kennedy Center Honors, when Ann and Nancy Wilson of Heart, backed by Jason Bonham—son of the late Zeppelin drummer John Bonham—on drums, gave an all-timer of a performance of “Stairway to Heaven.” President Obama and the First Lady were on hand. So was John Paul Jones, Zep’s bassist, as well as a beaming Jimmy Page and a weepy Robert Plant. I’d forgotten how powerful that performance was—and, to state the obvious here, something that powerful doesn’t happen if the musical selection is shit.

The song represents—along with Breaking Bad, Michael Jordan, Charlie Chaplin, and beignets from Café du Monde—one of those rare instances where impossible, larger-than-life hype is completely and totally deserved. Like the beignets, “Stairway” is a guilty, decadent pleasure. Like Chaplin, it’s universally popular—but more so in America than in Britain, where it was born. Like Jordan, it never loses. Whenever classic rock stations trot out their “Most Requested Songs” gimmick over some holiday weekend, “Stairway” is always, always, always number one. As Erik Davis argues in his book:

“Stairway to Heaven” isn’t the greatest rock song of the 1970s; it is the greatest spell of the 1970s. Think about it: we are all sick of the thing, but in some primordial way it is still number one. Everyone knows it. . . Even our dislike and mockery is ritualistic. The dumb parodies; the Wayne’s World-inspired folklore about guitar shops demanding customers not play it; even Robert Plant’s public disavowal of the song—all of these just prove the rule. “Stairway to Heaven” is not just number one. It is the One, the quintessence, the closest [that album-oriented rock] will ever get you to the absolute.

And like Breaking Bad, it presents both the very best and the very worst of the human condition. If there is light in “Stairway,” there is also darkness. Specifically, the Prince of Darkness, my sweet Satan. For we cannot write about “Stairway to Heaven” without discussing its alleged diabolical undertones: that is, if the record is played backwards in just the right moment, Luciferian messages are revealed. While the Devil rumors are silly, they are also sticky, so we may as well address them up front.

Ozzy Osbourne founded Black Sabbath, a band named for the Satanic mass. In his heyday, he bit the head off a live bat and otherwise behaved as though he was possessed by cacodaemons. As a solo artist, he wrote a song called “Mr. Crowley,” an ode to Aleister Crowley, the notorious occultist and black magic dabbler. In short, Ozzy has basically spent the last 50 years jumping up and down shouting, “Hey, guys! I worship Lucifer! Look! See how I’m making devil horns with my hands?!” And yet no one seems to object, probably because—and I say this as someone who loves John Michael Osbourne—Ozzy is not, and should not be, taken seriously. Jimmy Page, meanwhile, Led Zeppelin’s guitarist and main songwriter, evinces a scholarly interest in the occult, buys Crowley’s lakeside estate, maybe sneaks in some vague Satanic messages on an album as a lark, but otherwise keeps whatever sinister religious beliefs he may have to himself. . .and he’s somehow the Antichrist. How does that compute? If Page was ever into the devil, he certainly wasn’t proselytizing.

But then, it may be that the sneakiness of Zep’s occultism is what gives the Satan rumors legs. Unlike Sabbath, whose very name announces its daemonic affiliations, Led Zeppelin’s alleged allegiance to Our Dark Lord is back-masked on “Stairway to Heaven”—a song that, crucially, insists that “words have two meanings” but that “if you listen very hard, the tune will come to you at last.” For confirmation, we need only play the record backwards, in just the right spot, and all is revealed. Sort of.

What’s interesting about this, to me, is not that back-masked appeals to “my sweet Satan” can be heard—they can—but that this was discovered in the first place. Who the hell (pun intended) was the originator of this Q-worthy conspiracy theory, the prime mover who presumably sat around playing rock records backwards, seeking out Satan in his humming head? Nowadays, this sort of thing would be tracked back to some Reddit post, or maybe something Mike Flynn cooked up to rile up his acolytes. But before social media, news traveled way more slowly—it, ahem, winded on down the road. Like occult knowledge, it was distributed solely by word of mouth.

In his book, Davis traces the back-masking rumors as far back as 1981, to a Michigan minister, Michael Mills, who announced the findings on Christian radio, ten full years after the album’s release. While Mills was certainly the one who brought the infernal brouhaha into the mainstream, I have difficulty believing that this dorky reverend stumbled upon this himself. (If Mills did spend countless hours playing records backwards looking for dark artistry, that must have been a long lonely lonely lonely lonely lonely time.)

When I looked into it ten years ago, I found that the Satanic rumors began in 1975-77, a dark period in the life of Robert Plant, marked by a bad car wreck and the sudden death of his young son. That means that this bit of arcanum was known to Zep cognoscenti for years—perhaps leaked to a select few by the band’s mad genius manager, Peter Grant, a big believer in Word of Mouth. Think about it from a commercial standpoint: What better way to compel thousands of people to buy a ten-year-old record than a hidden endorsement from Satan Himself? How many copies did that Michigan minister personally purchase, only to destroy them by playing them backwards over and over? Did this idea originate with Page? Grant? Producer Andy Johns? Was it a complete coincidence? We’ll never know for sure, and in the end, it doesn’t matter.

“The fact is that, within two minutes of singing, ‘Stairway to Heaven’ contains at least seven reversed phrases of a suggestively devilish nature,” Davis writes, “. . .buried in a tune about pipers and whispers and listening really hard, a tune that, for a spell, ruled the world. I’m not saying supernatural forces are afoot. I’m just saying it makes you wonder.”

All of which would be more relevant to the task at hand—deciphering the meaning of the song—if the lyrics were written by the lone member of the band into the occult. But Jimmy Page didn’t write the words to “Stairway to Heaven.” Robert Plant did.

Plant was born in August of 1948 in the Black Country of the West Midlands. His father was a civil engineer. His mother was a homemaker, of Romany descent. He left home at 16, immersed himself in the blues, and four years later hooked up with Page to form Led Zeppelin. (Page was, and still is, almost five full years older.) As a teenager, Plant studied stamp collecting and the history of Roman Britain. His well-documented immersion into blues music meant that he hung around with a lot of squares like Steve Buschemi’s character in Ghost World. He read poetry and mythology and Tolkien.

Long story short: Robert Plant wasn’t into the occult; he was into hobbits.

As Davis reports in his book, the lyrics for “Stairway” were written late in the year 1970 at an old stone castle called Headley Grange—a dismal place that Plant did not like but Page thought was cool. The two of them were sitting by the fire one night, perhaps high on something perhaps not, and Plant scribbled down the first words to the song. He would later report that they came to him as if written automatically.

So: “Stairway” was composed by a 22-year-old closet geek, a Lord of the Rings fanboy who knew all about Vespasian’s run as governor of Britannia, while his de facto older brother, who may or may not have worshiped the devil but certainly liked to dabble in the occult, sat beside him, in a 200-year-old stone building that had once been a poorhouse, in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of the night. That’s wild!

Few songs have offered as wide a range of interpretations as “Stairway to Heaven.” The comment board at Songfacts contains any number of them, many interesting, many insane. Some find Satanic messages lurking; others read it as a Christian parable. RapGenius is all over the Biblical allusions. Plant himself remarked that his own interpretation changes all the time, and he wrote the freaking thing. Davis describes the lyrics perfectly: “It’s a zoo in there.”

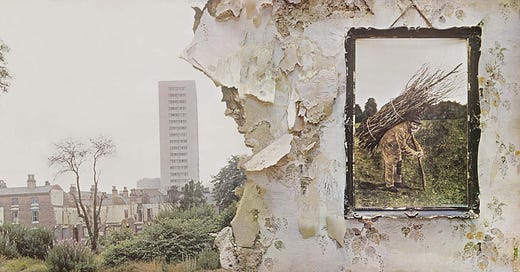

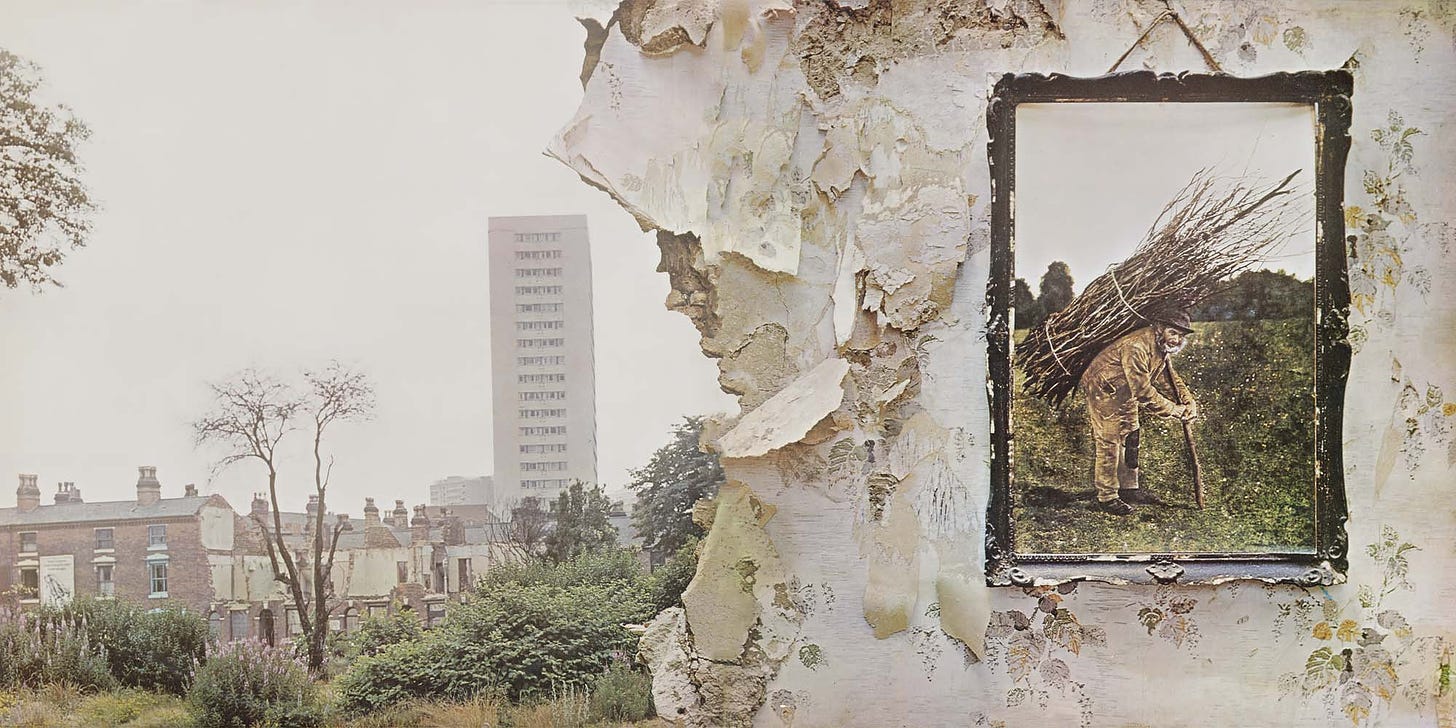

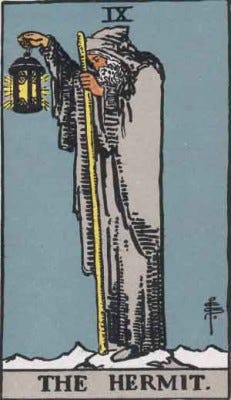

The cover of Led Zeppelin IV is a stylized version of the ninth major arcana tarot, The Hermit, while the inside cover—you know, the poster your roommate had on your wall freshman year in college—is almost identical to the Rider Deck image:

The four “runes” that comprise the album’s title represent the four tarot suits—Swords, Cups, Pentacles, and Wands/Staves, respectively. Here’s Davis on the runes:

The first thing that must be said is that there are four of them, and that they appear on the fourth record released by a quartet, a record that features four songs on each side…all these fours suggest the most fundamental of occult quaternities: Earth, Air, Fire, and Water, the four elements once believed to make up the whole of material reality. . .decisively linked to the four suits of the Tarot deck by the French magus Eliphas Levi. . . .Levi expanded magic’s network of correspondences by correlating Earth, Air, Fire, and Water to, respectively, [Pentacles], Swords, Wands, and Cups.

The band famously insisted that there be no writing on the cover at all, no band name or album title. This invites us to read the lyrics as symbols, or rather as interpretations of various symbols. If one wishes to get creative and retrofit the facts to support one’s operating theory—you know, like Sam Alito perusing old witchcraft statues—one might interpret “Stairway” as one long tarot card reading:2

The “Lady who’s sure all that glitters is gold” is The Empress. I’d always thought of this “lady” in the generic sense, as in “some lady at the supermarket,” but I’ve come to realize that there is an implicit capital “L” in the word. She has to be rich enough to purchase a shortcut to the Pearly Gates. (Perhaps this is a hint at selling one’s soul?)

The Three of Wands is one of the least fuzzy cards in the deck. It means one thing: “your spirit is crying for leaving.”

The Judgement card features a “piper who will lead us to reason.”

Wands/staves/rods correlate to the earth, to the vernal renewal process. The Queen of Wands rules the spring, which makes her—mirabile dictu—the May Queen. (“Bustle in the hedgerow,” incidentally, refers to a piece of a Victorian woman’s dress—a bustle—that has been discarded in the garden: the remains of last night’s orgy).

The High Priestess stands for mystery, the occult, hidden knowledge—all the stuff Jimmy Page is supposedly into. The “B” and “J” on the pillars behind her stand for Beelzebub and Jehovah—Satan or God, the binary choice, the “two paths you can go down.”

The last three cards encapsulate the reading. Here: the Fool is ready for the journey the piper’s calling him to join; encounters his deepest fears which give him pause (The Moon); and winds up as The Hanged Man, full of wisdom.

The final movement of “Stairway” achieves the same purpose, replaying the song’s conflict, only louder. We wind on down the road, and the “shadows taller than our souls” are the fears that paralyze us. But we find enlightenment. The key phrase is: “the tune will come to you at last.” This is a passive outcome. We do not come to the “tune,” but the other way around. Enlightenment is only achieved by stillness, quiet contemplation, and surrendering to the nature of things—“to be a rock and not to roll.”

The resolution to the conflict between material abundance (the purchased stairway) and spiritual salvation (heaven) is the yogic pose of stillness. Or something like that? Maybe? Like all tarot readings, the lyrics only cohere to a certain point. Which is, ultimately, what Plant was going for with the words: that they have two (at least) meanings.

Nowadays, what I love most about “Stairway to Heaven” is that, despite its spookiness—the song actually scared me a little back in middle school, the first time I really listened to it—it is ultimately hopeful and optimistic. We have all made mistakes. We have all held ugly opinions, said or written cringeworthy or unartful things we’ve come to regret, backed the wrong horse, been hurtful, inarticulate, or flat-out wrong. And that’s okay! As long as we are willing to take responsibility for our trespasses—no matter how shameful—we can learn, we can grow, we can evolve.

Plant’s musical declaration remains true, and will remain so until the hour of our death: There’s still time to change the road you’re on.

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Alex Aronson of Court Accountability. We talked a lot of Sam Alito:

Four Sticks Press News

The name of my small imprint, Four Sticks Press, also has two meanings. “Four Sticks” is, of course, the title of the second song on the second side of Led Zeppelin IV. And it indicates the Four of Wands tarot—the card of celebration.

There will be two titles put out by said imprint in the coming weeks, including an excellent novel not written by Yours Truly. But this week marks the release of my new book, Rough Beast: Who Donald Trump Really Is, What He’ll Do if Re-Elected, and Why Democracy Must Prevail, six years(!) almost to the day that Dirty Rubles dropped.

The paperback is available now on Amazon. The e-book will be available later this week. The Ingram Spark edition is also coming shortly, which means bookstores can order it. And I’m halfway done recording the audiobook.

I’ll share the introduction to the book on Tuesday, along with more information about it. In the meantime, here are the first two paragraphs:

Thanks for your support!

Technically, the title of the album is the four glyphs, which means the title of his book is the four glyphs as well, but italicized. Substack does not have the capability to do that, so I shall refer to it here as Led Zeppelin IV.

I did this ten years ago at The Weeklings, in a piece I’m revising today.

Thank you for writing this. I saw Led Zeppelin play “Stairway to Heaven” live in Cleveland at the Richfield Coliseum in April 1977, in the grips of a LedZep fever I’ve never been released from. A fever I’ve passed to my son and plan to pass to my grandson. Around the time I turned 50, I suddenly could “hear” Bonzo’s drums as the predominant driver of their songs, where I’d previously focused on Page’s skills with guitar. Their music became new to me again. But, tbf, their music will always be new to me. Thanks again.

Greg. Your range of interests is inspiring. Thanks maestro. Billserle.com