Dear Reader,

I came of age as a consumer of popular music in fifth grade—and, specifically, on Christmas morning, 1983, when Santa brought me an Emerson tape player and my first three cassettes: Duran Duran’s Seven and the Ragged Tiger, Touch by Eurythmics, and The Police’s Synchronicity.

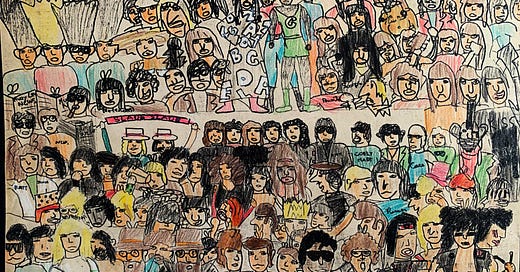

As it happened, this was a boom time for pop music. A new sound had evolved: heavy on the keyboards and the drum machines, with rousing electric guitar solos and vocals too high for me to sing along to without going down an octave, exemplified by songs like “Wake Me Up Before You Go-go,” “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun,” “Karma Chameleon,” “Into the Groove,” “Hungry Like the Wolf,” and pretty much any track on Thriller. In sixth grade, with clearly too much time on my hands, I drew this picture of all the bands I found notable at the time:

In the first row, you can see Van Halen, ZZ Top, Duran Duran, Michael Jackson and “Weird” Al Yankovic, and Mötley Crüe. I can also make out Culture Club, Quiet Riot, Madonna, Prince, Rush, Twisted Sister, Huey Lewis & the News, and The Cars. I think of these artists collectively as “80s Music.” But most of what I call “80s Music” was actually created between 1982-84—a three-year period of sonic awesomeness that ranks with any similar thousand-day interval in the history of pop music.

By April 1, 1985—when David Lee Roth quit Van Halen; the Day the Music Died—the bloom was off the musical rose. By the middle of the decade, there was a general backlash against “80s Music,” so much so that when Duran Duran’s Decade came out on November 15, 1989—two days after my 17th birthday!—I had to listen to it on the sly, for fear of being made fun of.

As far as music goes, the second half of the 1980s, let’s be honest, was pretty meh. There was good stuff out there—U2 and R.E.M. were the most important acts in my little world—but nothing that cohered into a distinctive, universal sound. It was, relatively speaking, a fallow period.

It was in that context, in the summer of ‘87, a few weeks before my freshman year of high school, that Guns N’ Roses appeared. They were scary-looking dudes from L.A., with tattoos and heroin-thin bodies. Their debut album was called Appetite for Destruction, and the cover featured a drawing of the skulls of the five band members. The lead guitarist had a stage name and a top hat and dark glasses. The front man had his long blonde hair pulled back with a bandana, and he slithered like a snake as he held the mic stand, and when he sang “You’re in the jungle, baby! You’re gonna die!” in that distinct scowl of a voice, you got the feeling that he wasn’t messing around.

All around me, people were going nuts for this album. And I understood that the band was legit good. Not just good; unique. GNR was like if Mötley Crüe (who I didn’t much enjoy as a listening experience) really did sell their souls to the devil and got back actual talent in exchange. So I appreciated it, but it wasn’t really my jam. I was a goody-two-shoes. Neither jungle nor Paradise City were places I wanted to be taken down to. I didn’t even have an appetite for tardiness, let alone full-on destruction.

And then I heard “Sweet Child O’Mine,” and O’my god. There might be songs just as good written in the last 40 years, but there isn’t one better.

The song opens with The Riff. The lead guitar, all alone, announcing itself. It soars. It thrills. It’s euphoric. I’m not remotely a headbanger, but I have never heard The Riff on the radio and not reflexively reached for the dial to crank up the volume. It is impossible to play it too loud. Slash—who wrote The Riff and played The Riff and found the perfect guitar sound for The Riff and in many ways built an entire career out of The Riff—now can’t stand The Riff, which is understandble. No matter.

Then, against that spectacular sonic backdrop, we hear the melody for the first time, teased out on the bass. There is nothing complicated here. The chord progression—D to C to G1—is one of the most common in rock music. But the tune feels simultaneously new and very old, like they didn’t write the song as much as discovered it on some cosmic archeological dig of ancient melody lines.

And then Axl Rose begins to sing:

She’s got a smile that it seems to me,

Reminds me of childhood memories,

Where everything was as fresh as the bright blue sky.

Now and then when I see her face,

She takes me away to that special place,

And if I stare too long, I’d probably break down and cry.

As with the melody, there’s nothing complicated here. The words are simple. The rhyme scheme is easy. But he’s comparing how he feels when he’s with his girlfriend to the happiest moments of his childhood. I can’t think of another song that does that in quite this way. It’s a beautiful, honest expression of love, as pure as the sound in The Riff, and I’ve always gotten the sense that he means it, that he’s not going through the motions, that this is Axl Rose at his most authentic. In the second verse, he reveals his vulnerability:

Her hair reminds me of a warm safe place,

Where as a child I’d hide,

And pray for the thunder

And the rain

To quietly pass me by.

In the annals of rock music, few love songs manage to convey how the love makes the singer feel more articulately than this. And then we remember who it is giving voice to this emotional outpouring: Axl Rose! The same guy who sang In the jungle / Welcome to the jungle / Feel my serpentine / I want to hear you scream with the appropriate menace is…afraid of thunderstorms. He’s no less vulnerable than anyone else!

And then we realize that his signature singing style—the drawing out of certain syllables, especially the long “i,” so that “mine” becomes “mi-ee-yine,” and sounds so fearsome on other tracks—is really just Axl channeling Frankie Valli, who sang the exact same way in, among many other examples, “Walk Like a Man”: Oh how you try-yied to cut me down to si-yize. Even the term of endearment that gives the song its title is anachronistic and old-timey, like it belongs in a standard from the 1940s. That “Sweet Child O’Mine” was written about Axl’s then-girlfriend Erin Everly—the daughter of Don Everly, half of The Everly Brothers—seems significant. There is a through line from “Bye Bye Love” and “Wake Up Little Suzie” to this: masterpieces, all.

The coda is an underused musical device in rock music. Beyond “Hey Jude” and “Layla,” there are few notable examples. With “November Rain” and “Sweet Child O’Mine,” GNR adds two more to the canon. Here, after one of my all-time favorite guitar solos, the song gets louder and shifts into a minor key—representing, perhaps, the transition from the innocence of true love to its heartbreaking experience. Axl sings the same line over and over, asking the same question again and again, as if he doesn’t want to hear the answer:

Where do we go? Where do we go now? Where do we go?

He might have been asking about music in general in 1987. It would take four years before the arrival of Nirvana and Tupac Shakur put grunge and hip hop, respectively, on the map, setting the tone for the new decade. For Guns N’ Roses, the answer to the question was one word: Down. When you’re at the top of the mountain, that’s the only place you can go.

Like “80s Music,” GNR could not stay. Four years after Appetite for Destruction, they finally released their highly anticipated double album Use Your Illusion I & II—decent records, but not really worth the wait. In 1991, Izzy Stradlin—a critical piece of the songwriting—left the band for good. Slash and bassist Duff McKagan followed a few years later. Axl unraveled. The stories about his behavior, especially towards women, were not good. Yet somehow, by some divine miracle, this band of troubled souls gave us one of the purest and most moving rock ballads of all time.

Where do we go, you ask? Why do we have to go anywhere?

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was the British former diplomat and “Behind the Lines” podcaster Arthur Snell:

We also did an Afterhours. Usually open only to members, we decided to make this one available to all, because we had a special guest: documentary filmmaker Sandi Bacom.

GNR tuned down half a step, to be cool.

You are quite the artist! Glad you mentioned Frankie Valli--the greatest falsetto singer of all time! Only he could get away with singing a song called "Walk Like a Man" in falsetto. He is oft imitated, but never equaled.

Interesting wade into the dredges of music history Greg! Love the writing and accompanying emotion that rides alongside the musical ride through the roughest patches in mainstream rock-pop culture.

Your Sunday post are always insightful to the path that created your brilliance!!