Sunday Pages: "The Apprentice"

A film by Ali Abbasi

Dear Reader,

One of the great ironies about Donald Trump, Sr.—the most discussed, most lampooned, most satirized, most psychoanalyzed-from-afar, and easily the most famous figure of the 21st century—is that, like all autocrats, he is fantastically boring. To hide his inherent meh-ness, he swaddled himself in mythologies: Donald Trump the builder, Donald Trump the playboy, Donald Trump the New York tabloid fixture, Donald Trump the reality show host, Donald Trump the MAGA overlord. (If we hate him, we might add: Donald Trump the mob underboss, Donald Trump the Putin fanboy, Donald Trump the sexual predator, and Donald Trump the American Hitler.) To wallpaper over this gaping deficit of soul, he had to become a caricature of himself. Hence the small-box-of-Crayola uniform he dons (ha ha) every day: blue suit, white shirt, red tie and hat, orange face, yellow hair.

But unwrap all that lore, peel away the layers of the big mythological onion, doff the primary-colored uniform, and what remains? Not much of note. An insecure, unlovable bully, desperate for everyone—but rich, famous, and powerful people especially—to respect him, if not love him. This profound, debilitating insecurity is what animates his drive to succeed, and his achievements exist only to feed an insatiable need for positive regard. There’s nothing interesting about that kind of character. We’ve seen it a million times in movies, TV shows, novels—so many times that even Donald’s true self is a cliché. Yawn.

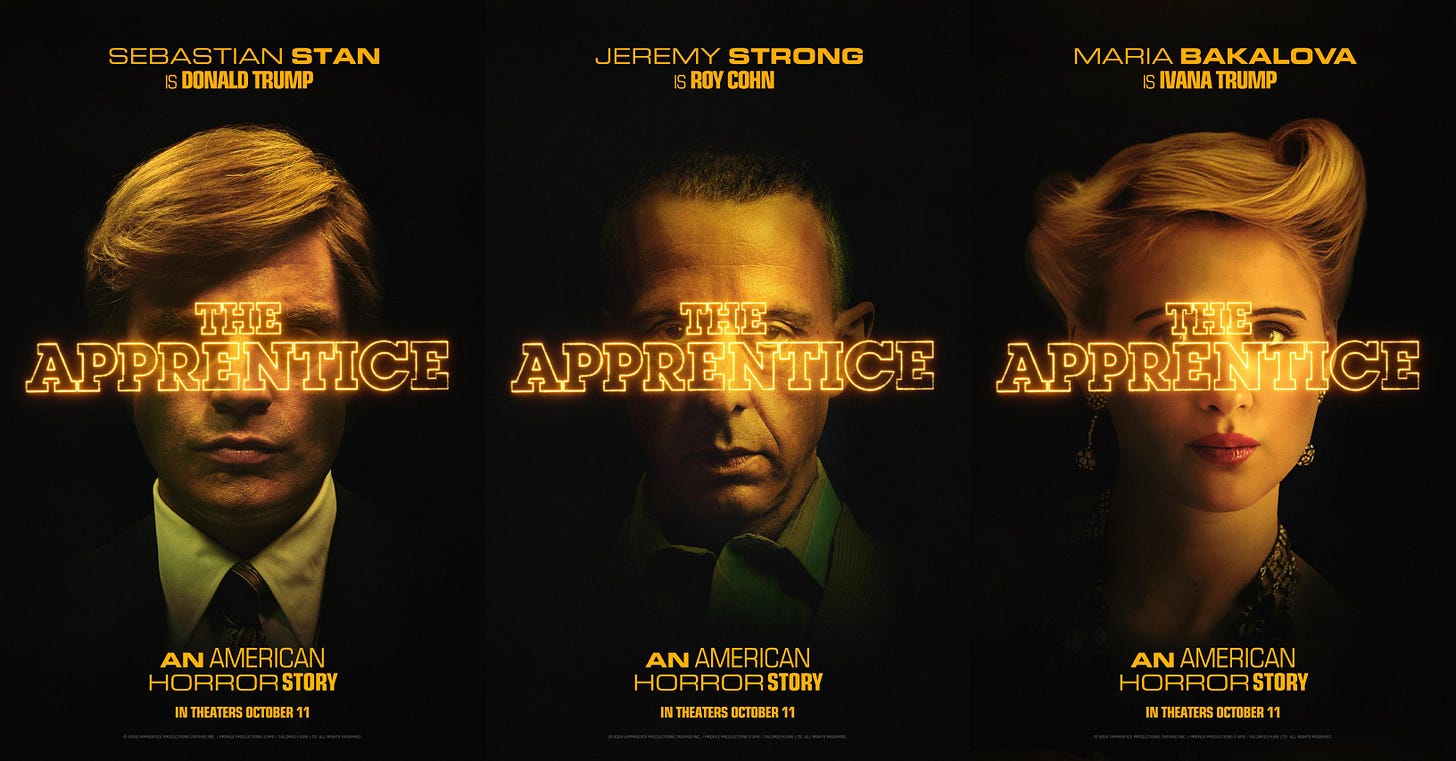

And that is what makes The Apprentice, the new Trump biopic by the Iranian-Danish filmmaker Ali Abbasi, such an accomplishment, and Sebastian Stan’s performance as the main character so exquisitely compelling. Making cinematic gold out of this lame story is nothing less than filmmaking alchemy.

I saw the movie Thursday in Hyde Park, at the first showing on the day of its release, at the Roosevelt Theatre—so named because the cinema sits just across the street from the FDR Presidential Library. The proximity to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s gravesite, and all of the historically important documents and artifacts assembled there, somehow gave the whole enterprise more significance. In the long shadow of one of the nation’s best presidents, I’d come to see a picture about one of its worst.

For me, there is always some anxiety, watching a film about Trump. Like, I’ve now spent almost eight years writing about this guy, and my feelings on the subject are, at this point, proprietary. I know too much not to nitpick. As I sat back in the comfy recliner and dug into the buttery popcorn—remembering how, in the old days of Twitter, any possible Mueller update filled my feed with popcorn emojis—I began to stress. Would they get stuff wrong? (Or, worse: had I gotten stuff wrong?) Would they go into Trump’s partnership with the mob? With Russia? How about Fred Trump’s association with the Genovese crime family? Would the release of the film a month before the election move the needle at all? Would it—gasp—move the needle the wrong way? What would Trump think of it? What would MAGA think of it? Was the only other guy in the otherwise-empty theater a Trump supporter? (Also: How long has this popcorn been sitting out? Because it isn’t warm enough.)

Happily, all of those worries melted away like popcorn butter almost as soon as the movie began—with a shot of Richard Nixon at that notorious press conference in November 1973, looking right at me, speaking right to me:

Let me just say this. And I want to say this to the television audience. I made my mistakes, but in all of my years of public life I have never profited, never profited from public service. I’ve earned every cent. And in all of my years in public life I have never obstructed justice. And I think, too, that I can say that in my years of public life that I welcome this kind of examination because people have got to know whether or not their President is a crook. Well I’m not a crook. I’ve earned everything I’ve got.

The subtext of that opening put my mind at ease. And just as quickly, I forgot my other worries, too. It didn’t matter what was right or wrong, or if I could discern fact from artistic license; this wasn’t an examination, I wasn’t being graded. The movie almost immediately transported me from the Roosevelt Theatre in 2024 to the New York City of the early 1970s. The Apprentice is, among other things, a New York film, and I love New York films. This one looks amazing: the period suits and ties, the too-big-to-parallel-park Cadillacs, the dimly-lit members-only clubs, the glamorous women all looking like Laraine Newman in the first season of SNL, 42nd Street in all its seedy glory (or whatever the opposite of glory is), and, yes, the handsome face of the film’s eponymous protagonist, crowned with a majestic Redfordian coif.

At rise, Donald is 27 years old. He works at a rent collector at his old man’s apartment complex: a lowly position in the family business. He is a solitary figure, aloof. He has watched his older brother try in vain to win the pride of his father, and he wants to succeed where Freddy has failed. Ambition radiates off him like stink from a fart. He is hungry. He wants.

An apprentice needs a master, and young Donald soon finds one in the person of 46-year-old Roy Cohn—former federal prosecutor, former Joe McCarthy chief counsel, hard SOB who sent the Rosenbergs to the electric chair—played with steely menace and pitch-perfect Bronx accent by Jeremy Strong (who clearly has a thing for characters named Roy). When we meet Cohn, he is ensconced in a private room in the private club, surrounded by movers and shakers like “Fat Tony” Salerno, head of the Genovese crime family (who, alas, never reappears). Others in his orbit include Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, Rupert Murdoch, and Andy Warhol, the pop artist who Trump, to great comic effect, does not recognize.

Donald likes Roy because he wants to be him; Roy likes Donald because he wants to do him. The latter never happens; the former does, and is the subject of The Apprentice, which spans the pair’s first meeting in late 1973 to Cohn’s death in 1986.

I must confess, after about ten minutes, I found myself forgetting that this was a movie about the early life of the hateful fascist now running for president. Through what actorly hocus pocus I do not know, Sebastian Stan makes Trump sympathetic(!). There are moments in the film, early on, when I found myself, in spite of myself, rooting for him. We are conditioned to have such feelings in movies like this; if we aren’t invested, the film fails. We want the main character to stand up to his asshole father, to make his own way, to succeed.

And succeed young Donald does. He learns ruthlessness at the feet of his ruthless master. He elbows his way into the tabloids. In his tangles with Mayor Ed Koch, who calls him out on his shady business practices (i.e., stiffing his workers), he workshops modes of attack with which we have all become familiar. He realizes his dream of turning the decrepit Commodore Hotel—a boarded-up husk of a building at Grand Central, with hookers and drug dealers patrolling the streets outside, in a graffitied Midtown Manhattan that today’s Trump wants the rest of America to believe NYC still looks like—into something special. He promises to bring New York back. And he is part of its renaissance. Or so the film asks us to believe.

The Apprentice covers a lot of linear time, but its focus is narrow. Other than Trump and Cohn, the only other major characters are Donald’s father, Fred, the abusive, jealous, probably sociopathic real estate magnate; his brother, the oft-abused Freddy, portrayed in the film as a fuck-up, a sad and hopeless drunk; and his equally ambitious wife, the former Ivana Zelníčková, played by Maria Bakalova, last seen running away from Rudy Giuliani’s hotel room in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. Rudy didn’t get her, but Donald does.

And here is where I shall issue my

SPOILER ALERT: Don’t read on if you don’t want to know what happens. (Also, what happens is upsetting for a Sunday morning.)

We know about Donald’s rape of Ivana from her sworn divorce deposition, and we know about the sworn divorce deposition from Lost Tycoon: The Many Lives of Donald J. Trump, Harry Hunt III’s 1993 unauthorized biography. That long-dormant story bubbled up again during Trump’s 2016 campaign. As Jane Mayer explained in 2017:

The part of the book that caused the most controversy concerns Trump’s divorce from his first wife, Ivana. Hurt obtained a copy of her sworn divorce deposition, from 1990, in which she stated that, the previous year, her husband had raped her in a fit of rage. In Hurt’s account, Trump was furious that a “scalp reduction” operation he’d undergone to eliminate a bald spot had been unexpectedly painful. Ivana had recommended the plastic surgeon. In retaliation, Hurt wrote, Trump yanked out a handful of his wife’s hair, and then forced himself on her sexually. Afterward, according to the book, she spent the night locked in a bedroom, crying; in the morning, Trump asked her, “with menacing casualness, ‘Does it hurt?’” Trump has denied both the rape allegation and the suggestion that he had a scalp-reduction procedure. Hurt said that the incident, which is detailed in Ivana’s deposition, was confirmed by two of her friends.

After the marital rape allegation resurfaced, Michael Cohen, then still Trump’s personal attorney, was at his most vicious in shutting the story down. (“You can’t rape your spouse,” he wrongly claimed.)

The Apprentice takes this account as the truth—which, given its mention in a sworn deposition and, per Hunt, its corroboration by two of Ivana’s friends, it almost certainly is. And we bear witness to that act of sadistic violence and mocking cruelty. As I watched the scene unfold, and realized what was about to happen, the only thing stopping me from falling out of my chair was the reclining seat being impossible to fall out of.

The rape of Ivana is the most important scene in the film. It is at that moment when any vestige of kindness or grace or human decency left in Donald’s soul flies away forever, when Mr. Hyde kills off Dr. Jekyll, when Anakin Skywalker becomes Darth Vader—or, more accurately, when Donald Trump becomes Roy Cohn. That he is able to physically perform in that moment, just after telling Ivana he is no longer sexually attracted to her, is also important: his addiction to diet pills, his lack of quality sleep, and his swollen belly have left him struggling with erectile dysfunction. The message here is clear: Only rape arouses this monster now.

Doubling down on Hunt’s reporting, the film also shows the scalp reduction surgery, which Donald undergoes along with liposuction; he doesn’t believe in exercise, and wants to lose the fat the easy way. But in The Apprentice, the surgery happens after the rape, not before it, and is not botched. Artistic license, don’t you know. (My guess is, the visually yuck scenes of Trump undergoing cosmetic surgery will vex him, and any MAGA who might see the film, much more than the marital rape sequence.)

With that said, anyone hoping for a beat-down of the subject will leave the cinema disappointed. The Apprentice is not a polemical film. Its critique of Donald is artful and subtle—but there is great power in art and subtlety. From an anti-Trump propaganda standpoint, Abbasi provides three things:

First, by treating the rape of Ivana as fact, and showing it how he did and when he did, Abbasi brings Donald’s abominable history of sexual violence back to the fore. We are now free to openly discuss this heinous act in the public discourse, in a way we weren’t before. It is now perfectly acceptable, if not journalistically necessary given his campaign’s rank misogyny, to ask Ivanka Trump how she can continue to support the sexual predator who raped her namesake mother.1

Second, the subtext in the film is searing. In one scene, Roy Cohn is telling Donald about how and why he insisted that Ethel Rosenberg get the electric chair, and should not be spared just because she happened to be the mother of young children. There is a close shot of his face as he says (I’m paraphrasing here): “It was treason. She betrayed the country, and so she had to die.” That’s the filmmakers speaking directly to Trump, about Trump.

And finally: nothing about Donald Trump is real. It’s all an act, and the act is an appropriation. Like Dick Whitman stealing the identity of a dead man and constructing the persona of Don Draper, the Donald Trump we know and loathe today is nothing more than Roy Cohn in a fat suit. Everything that he is, every principle he lives by, every strategy he employs, every heartless decision he makes to condemn someone to death—it’s merely Roy Cohn 2.0.

In the scene where we meet Roger Stone for the first time—because Cohn hooked Stone up with Trump, just as he hooked Rupert Murdoch up with Trump, and god knows how many mobsters—Trump is sitting next to Cohn, who is stretched out upon a tanning bed. His skin, one can’t help but notice, is not bronze but orange. Even that, the film is telling us, one of the trademark aspects of Donald’s physical appearance, is purloined from Roy Cohn.

The world of literature knows Cohn from Angels in America, the breathtaking Tony Kushner play set in the darkest days of the AIDS crisis. In the play, too, he is an attack dog who refuses to accept reality and never admits defeat. The master who taught Trump everything he knows died of complications from HIV, denying to his dying breath that he had AIDS. He passed away a few weeks after his legal disbarment—he’d forged the signature of a comatose client, making himself the executor of his estate. In the grand scheme of his lifetime of evildoing, the disbarment was small potatoes, but also just desserts.

Cohn suffered mightily, and he died miserably and alone—but he lived just long enough to watch all his power and influence evaporate, and to know the sting of public shame and the humiliation of legal trouble. In the end, the man who denied everything could not deny to himself that he was a loser.

May his apprentice meet the same fate.

ICYMI

Our guest on The Five 8 was Tony Michaels:

This was pointed out to me by LB during our Five 8 production meeting.

“Ambition radiates off him like stink from a fart”

this description really stood out, Greg.

-perfectly apposite.

I went and saw it yesterday and there were more than a few moments that were chilling. Are you a killer donald? Ugh to think he buried her in his golf course. Have you read Mary Trumps “how could anyone love you? Made the scenes with Fred jr really painful.