Dear Reader,

The last two Sundays, I’ve written about Shakespeare and the Beatles. Keeping with this theme of all-time-great artistic geniuses who were British, I will write today about Charlie Chaplin—and in particular, his satirical classic, The Great Dictator.

I first saw this film in 1997 or 98. It happened to be on AMC that night, and I happened to catch it just as it was starting. I’d never seen a Chaplin movie before, and I was expecting it to be 1) dated, 2) silent, and 3) overrated. It was none of those things. Watching the film, I was stunned at how good it was, how topical, and how funny. Clearly Mel Brooks and Woody Allen watched a lot of Chaplin, because so much of their humor has its antecedent here.

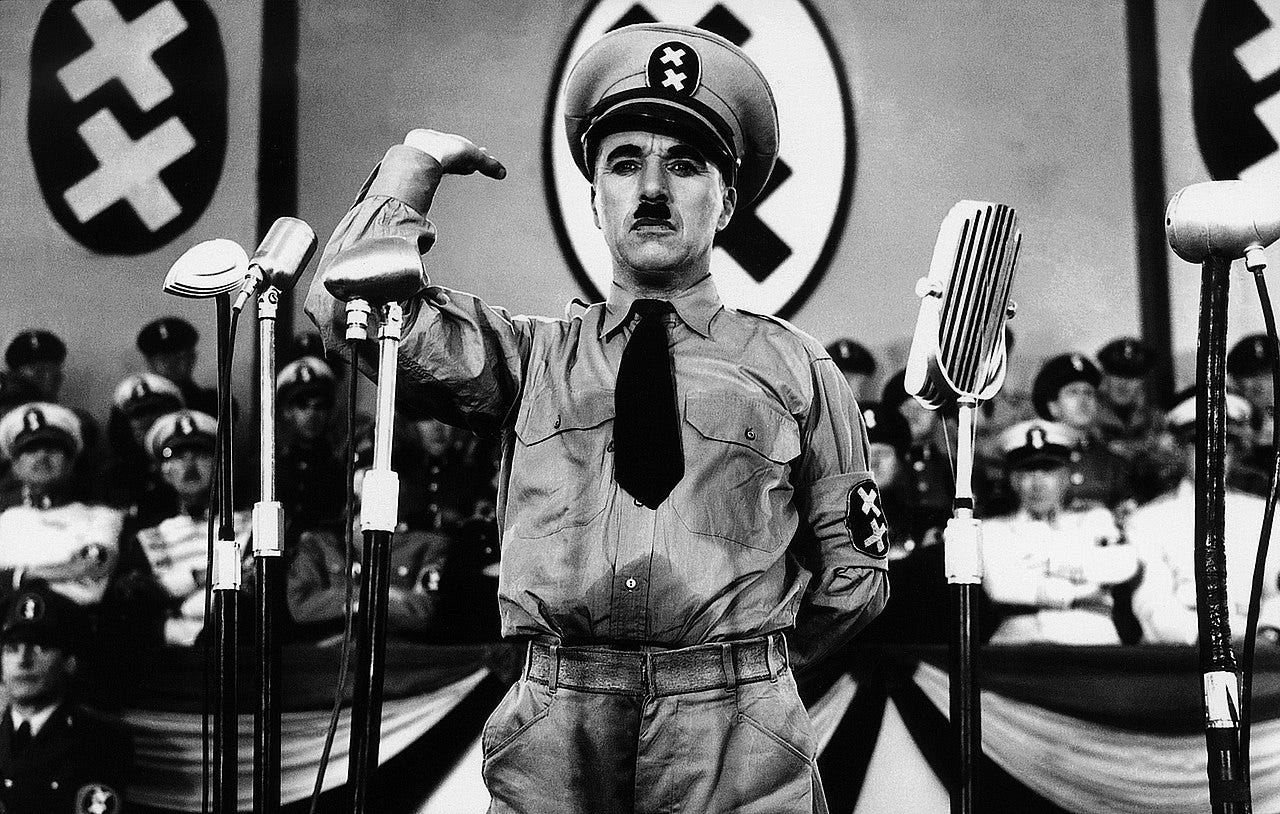

The plot of The Great Dictator concerns a Jewish barber (played by Chaplin) who is injured in the Great War and develops a case of amnesia. He returns to the ghetto after 20 years in hospital to find a very different world. The country of Tomainia, for which he fought in the war, has been taken over by a dictator named Adenoid Hynkel—who bears a striking resemblance to another strongman with the initials A.H.: same physical size, same mannerisms, same spit-speckled oratory, same Charlie Chaplin moustache. But instead of a Swastika, there is (ha!) a Double Cross.

This is Chaplin’s first “talkie.” And boy, does he talk!

Chaplin was inspired to make The Great Dictator after watching Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film, Triumph of the Will. While others watched the movie in horror, terrified at the power of its propaganda, Chaplin saw right through it. He cracked up watching the thing, and used it and newsreel footage of Hitler to hone his mocking impression. (He abhorred Hitler, who had appropriated his Tramp moustache, supposedly to make himself more popular). The scene where Hynkel meets his corpulent counterpart, Benzino Napaloni, the Diggaditchie of Bacteria, is one of the funniest sequences in the history of cinema. (The dynamic between two strongmen, one slender and one plump, also foreshadows the Putin-Trump relationship, albeit with the roles reversed).

From what I gather, Hitler genuinely admired Chaplin, rather like Chris Christie is a Bruce Springsteen fanboy. He banned The Great Dictator from Germany, but smuggled in a copy for himself. History does not record his reaction—but it is reported that he watched it twice.

What’s really amazing about The Great Dictator, though, is when it was made. Chaplin—who wrote, directed, played two parts in, wrote most of the music for, and produced the picture—began filming in September of 1939, soon after Hitler invaded Poland, and World War II began. He’d obviously been working on the script for months before that. While the Führer’s positions on both war and Jews were obvious to anyone who cared to look in the 1930s, plenty of moviegoers in the United States and Great Britain were Nazi sympathizers—including the abdicated British king, Edward VIII, and his wife, the twice-divorced American socialite (and alleged Nazi spy) Wallis Simpson. The existence of Nazi concentration camps was known—the Jewish barber is sent to one in the film—but the extent of the atrocities committed there was not. Thus, in 1939, when The Great Dictator was shot, and in 1940, when the film was released, it was a risk, making an overtly political film like this. Chaplin did it anyway.

And he paid the price. J. Edgar Hoover, the corrupt FBI director, had it in for Charlie Chaplin, whom he considered a Communist—never mind that the filmmaker was a co-founder of United Artists and one of the wealthiest men in Hollywood. A staunch defender of civil liberties, Chaplin was a vocal opponent of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Because he was not an American citizen, he was dragged in the press—through Hoover’s media stooges—as a Communist sympathizer. Rep. John E. Rankin of Mississippi, the Jim Jordan of his era, lobbied for Chaplin’s deportation, so that “his loathsome pictures can be kept from before the eyes of the American youth.” In 1952, Chaplin went to London for the premiere of his film Limelight. When he tried to return to the United States, he found that his re-entry permit had been revoked. He never went back, spending the last 25 years of his life in Europe. So yes, Chaplin was punished for mocking Hitler, and speaking out against the despotic tactics of HUAC.

The Great Dictator ends with a remarkable speech, one of the all-time great film monologues, given to the world by the Jewish barber. Here is an excerpt. As you can see, it remains just as relevant in 2021 as it was eight decades ago:

Greed has poisoned men’s souls, has barricaded the world with hate, has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed. We have developed speed, but we have shut ourselves in. Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical. Our cleverness, hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost. . .

The airplane and the radio have brought us closer together. The very nature of these inventions cries out for the goodness in men—cries out for universal brotherhood, for the unity of us all. Even now my voice is reaching millions throughout the world. . . .

To those who can hear me, I say: Do not despair. The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed—the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress. The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people. And so long as men die, liberty will never perish . . .

You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful. . . Then, in the name of democracy, let us use that power. Let us all unite. Let us fight for a new world—a decent world that will give men a chance to work, that will give youth a future and old age a security. By the promise of these things, brutes have risen to power. But they lie! They do not fulfil that promise. They never will!

Dictators free themselves, but they enslave the people! Now let us fight to fulfil that promise! Let us fight to free the world. . . to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance. Let us fight for a world of reason, a world where science and progress will lead to all men’s happiness. . . In the name of democracy, let us all unite!

I think this is one of your best pieces. I needed to read it. You, Eric Boehlert and Heather Cox Richardson help me stay sane. Thank you.

Timely. Thank you.