Dear Reader,

There are certain songs of Bruce Springsteen that capture a spirit of improbable victory—triumph over long odds. I’m speaking of “Rosalita” and Born to Run” and “Thunder Road,” three songs that boil down to The Boss trying to talk Rosie/Wendy/Mary into hopping in his car and racing out of town. When he sings about the record company giving him a big advance, or dying on the street in an everlasting kiss, or pulling out of Losertown to win, I get this vicarious surge of adrenaline—like I too will conquer New Jersey, like I too will prevail. (It is a feeling I don’t get much these days outside of music or literature; even when nice things happen, Trump has muffled the good emotions; there is a collective deficit of joy.) Bruce is so earnest, so sure of himself, that it doesn’t matter that, in all three cases, his ultimate quest is futile. Neither Rosie nor Wendy nor Mary ride off with him. In real life as in song, Springsteen remains a resident of my home state.

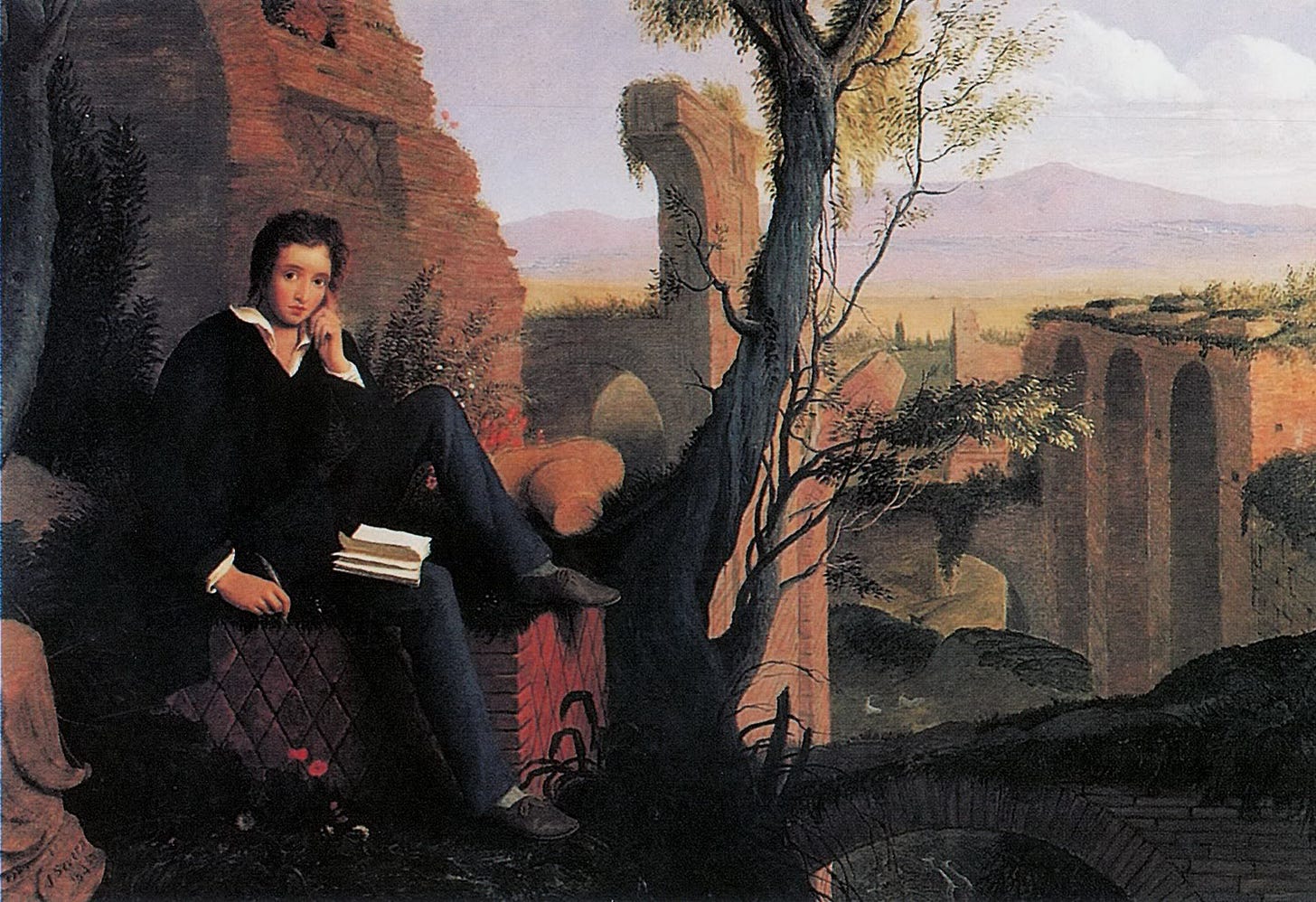

I get the same adrenaline jolt when reading Shelley’s poem “Ode to the West Wind.” Despite his fuddy-duddy name, Percy Bysshe Shelley was a literary rock star—Bruce Springsteen for the Romantic period. Except that, while Springsteen’s narrators remain mired in New Jersey, Shelley really did escape England—only to perish in a shipwreck off the coast of Italy a month before his 30th birthday. Live fast, die young, leave a good-looking chapbook.

Shelley was a child of revolution. Born in 1792—the same year President George Washington established the U.S. Postal Service, the same year the city of Washington was founded, the same year the French king Louis XVI abdicated, the same year Shelley’s eventual mother-in-law, Mary Wollstonecraft, published A Vindication of the Rights of Women—he came of age during the Napoleonic Wars, a period of great tumult and sea change in the Western world. His verse incorporates that same spirit of tumult and revolution. Poets.org writes that his “literary career was marked with controversy due to his views on religion, atheism, socialism, and free love,” which nicely sums it up. He and his wife, Mary Shelley, are English literature’s greatest power couple, the Kurt and Courtney of British Romanticism.

When I taught creative writing, my undergraduates never seemed to dig “Ode to the West Wind.” I can understand why. There’s lots of fancy-pants wordplay, difficult sentence construction, unusual imagery, and, oh yeah, it’s kind of long: five verses of 14 lines each. It’s almost like a five-pack of sonnets. But “Ode to the West Wind” is one of my favorite poems; it goes places other poems don’t. To fully appreciate its power, it must be read aloud. Preferably in your best Orson Welles/Richard Burton (or Maggie Smith/Judi Dench) voice. I like to do this every year at the autumnal equinox.

Right off the bat, “Ode to the West Wind” is not an ode, at least not how I understand odes. There’s nothing ode-ish about it. An ode, to me, is a poetical meditation on a given subject, a singing of its praises. “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is a good example; Keats contemplates the urn, and the poem results from where this contemplation takes him. But “Ode to the West Wind” is not about the West Wind, per se; rather, it’s a summoning of the West Wind. It is, as Shelley puts it, an incantation. The poet is at a low point, a moment of weakness and sapped energy, of despair and creative block, and is calling on the awesome (in the Romantic, and not the Valley Girl, sense of the word) power of the West Wind to help him.

In the first three verses, Shelley marvels at the might of the West Wind, noting its effect on leaves, clouds, and ocean waves. He starts small, with an image of dead leaves “driven / Like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,” establishing early the metaphysical element, and then builds. In the second verse, the leaves are compared to “loose clouds,” from which, by the power of the West Wind, “Black rain, and hail, and fire will burst.” By the third verse, even the “Atlantic’s level powers / Cleave themselves into chasms” as the wind fiercely blows; even the plants at the bottom of the ocean fear his might. There’s so much imagery of swirling, of rising, of crescendo, that it feels as if the poet himself is generating all this movement, like some sorcerer from Earthsea.

The last two verses are the most important. Here, Shelley introduces himself into the proceedings, calling upon the West Wind to do to him, metaphorically, what it literally does to leaves, clouds, and waves. He wants the West Wind to possess him. Be thou me, impetuous one!

When I read the poem out loud, I can feel the power he summons coursing through me. I can feel the raw energy of these words, these “dead thoughts,” written by a man who drowned almost 200 years ago, culminating in the famous last line. Ultimately, this is a poem about hope, about the restoration of creative power, about the difficulty and frustration of having to wait through the dark months—the “heavy weight of hours”—before the rebirth begins.

As this has been a particularly dark week in the history of this country, I wanted to share the last two verses of the poem today. (You can read it in full here, and you can listen to me read it in a cringingly pretentious faux-British/supervillain accent here).

Shelley knew, he knew, that he would prevail.

I feel the same way.

IV

If I were a dead leaf thou mightest bear;

If I were a swift cloud to fly with thee;

A wave to pant beneath thy power, and share

The impulse of thy strength, only less free

Than thou, O Uncontrollable! If even

I were as in my boyhood, and could be

The comrade of thy wanderings over Heaven,

As then, when to outstrip thy skiey speed

Scarce seemed a vision; I would ne’er have striven

As thus with thee in prayer in my sore need.

Oh! lift me as a wave, a leaf, a cloud!

I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!

A heavy weight of hours has chained and bowed

One too like thee: tameless, and swift, and proud.

V

Make me thy lyre, even as the forest is:

What if my leaves are falling like its own!

The tumult of thy mighty harmonies

Will take from both a deep, autumnal tone,

Sweet though in sadness. Be thou, Spirit fierce,

My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguished hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawakened Earth

The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

lovely. poetry read aloud gives the words wings. i did not know he died young.

Sounds like echoes of LB's contention that we're at the "darkness before the dawn" phase of US history hopefully? PS: Shelley's story about cheating with Mary on his first wife and the speculation that he was offed in the lake (once a cheater....) makes him very interesting to my seniors :)