Fifty years ago, at 9:26 in the evening New Jersey time, I came into the world. My parents were high school sweethearts who married right after college graduation. My father was 24 when I was born, my mother still 23: young, so young. I had a big head, like my dad, so they named me after him.

I was the first baby of my generation born in the extended family, and I was a week late. There were any number of parents, sisters, uncles, aunts, and cousins in the waiting room, anxiously awaiting my arrival in the not-so-quiet Italian way. “Oh,” the doctor quipped to my mom, “you’re the one with the fan club.”

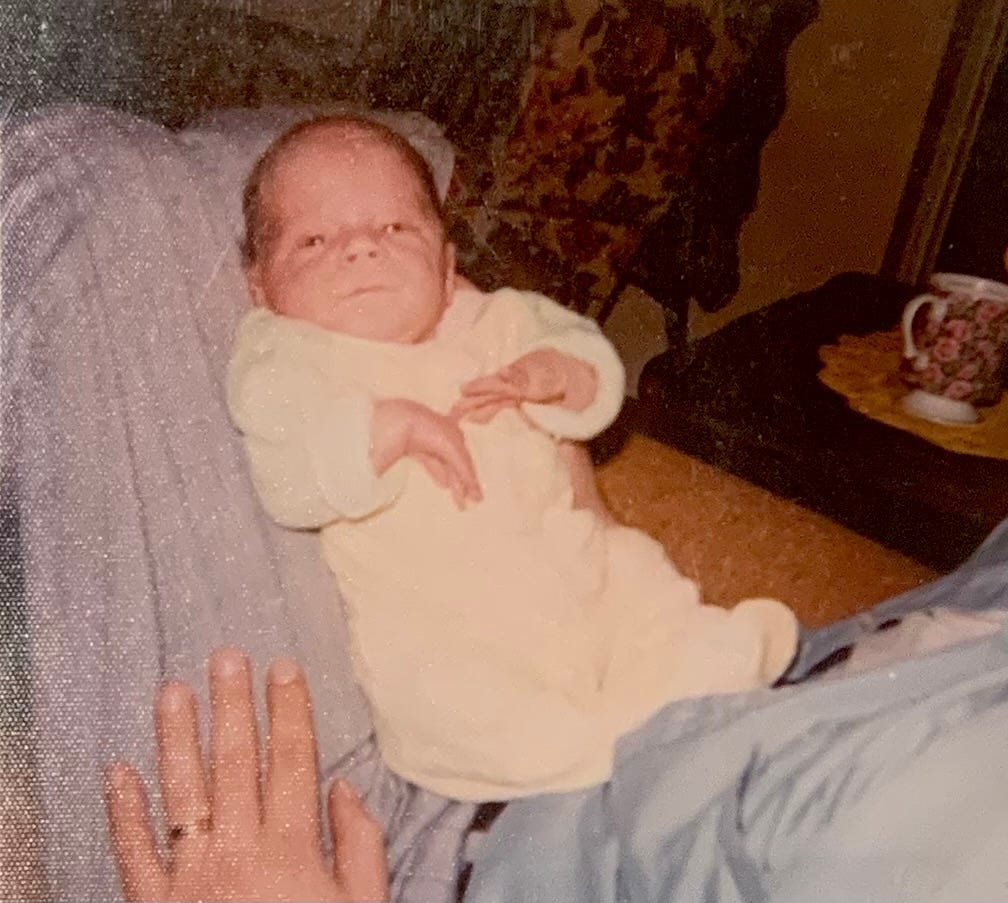

My mother might disagree, but objectively speaking, I was not a particularly cute baby. I was one of those newborns that look like a little old man: Don Rickles, in my case (see the photo above). Today, officially, I am the old man I was born to be.

When I saw that my fiftieth birthday fell on a Sunday, I knew I had to write something about it for “Sunday Pages.” My first idea was to dig up the little essay I wrote when I turned 40, and use that as a basis for an updated entry. Maybe I’d comment on it, maybe I’d cannibalize it. But when I went back into the archive and read what I’d written ten years ago, I was shocked by how lousy that piece was, how immature. It was primarily about money and success and how I didn’t have enough of either—cringe!—and there is a forced levity to the writing that made me recoil in mortification. This, I thought, is why writers burn their old work! Literally nothing that I wrote about ten years ago interests me now. As Morrissey once wondered: Has the world changed, or have I changed?

Eliot was a young man when he wrote about the not-quite-gracefully-aging Prufrock:

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?

But though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed,

Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter,

I am no prophet — and here’s no great matter;

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

Six years ago, Trump happened, and I began to write about him and the various villains, criminals, cronies, and Russians in his orbit. Not quite three years ago, the pandemic happened. Those two events, taken together, have obliterated my sense of time, have malwared my memory. Age, too, has done its dread work: another decade added to the ledger, stretching out the timeline of my life, all the things that happened before the cataclysm of 2016-2022 slowly receding like a middle-aged man’s hairline (but not, thankfully, the hairline of this middle-aged man!).

My first attempt at a novel, written my senior year in college and mercifully unpublished, was called My Brain Is Full—the title taken from “The Far Side.” Cracking wise, I wrote those four words in chalk on my mortarboard at graduation. Little did I know how many terabytes I had left on the hard drive of my mind!

Today, alas, the prophesy seems to have come true. My brain, full up, feels frayed. There is so much to remember, so much I forget. I’m constantly worried that I neglected to write someone back, forever doubting the accuracy of what I manage to summon from my cerebral filing system. I’ve always had a great memory; it let me coast through high school and college. So I am become a pitcher who has lost his fastball. But there is a certain kind of freedom that comes with this, as Pope hints at:

How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot.

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each pray’r accepted, and each wish resign’d;

Getting old, it seems to me, is about coping with loss. Memories fade. Loved ones die. Old friends fall away. Photographs and manuscripts disappear. Artists we admire turn out to be irredeemable jerks (looking at you, Morrissey). Creepy South African billionaires blow up Twitter. And so on. From here on out, the losses will only get more painful—that is the cost of being alive—and however desperately the Jared Kushners of the world seek immortality, for billionaire and pauper alike, life ends always in death. Larkin put it best:

And however you bank your screw, the money you save

Won’t in the end buy you more than a shave.

(The “shave,” he means, given by the undertaker.)

The way to cope with loss, it seems to me, is to keep moving forward. (To Mastodon we go!) Like a running back striving for a first down, we must keep the legs churning until the whistle blows: move the chains, move the chains. I’ve written about Tennyson’s “Ulysses” before, and used it as the epigraph to Dirty Rubles, but it speaks to me still, because it concerns past-their-prime men who still want to contribute:

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil’d, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

’Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

The petty concerns I wrote about ten years ago are today in my rearview. Reflecting on my half-century, what I feel right now, above all, is gratitude. Gratitude to have made it this far. Gratitude to my parents—and to my grandparents and extended family; my “fan club”— for raising me right, for encouraging my quixotic pursuits, for making me always feel safe and well looked after. Gratitude to my teachers—I had so many good ones. Gratitude to my wife, for 22 years and counting of love, companionship, togetherness, and laughs. Gratitude to my kids, who I hope will remember me fondly when I’m gone. Gratitude to my friends, old and new, IRL and online only, for enriching my life in so many magical ways. And gratitude to you, Dear Reader, for giving me the one thing that all writers want and need above all else: to be read.

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous—

Almost, at times, the Fool.

Thank you for making my fiftieth a happy birthday.

Poems excerpted: “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” by T.S. Eliot; “Eloisa to Abelard,” by Alexander Pope; “Money,” by Philip Larkin; “Ulysses,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson; and Eliot again.

Photo credits: My mom, 49 years and 50 weeks ago; my son, last night.

It's amazing how much the infant Greg looks like the fully ripe Greg. Fifty is just the end of the beginning. Much more still to come. Happy birthday, dear Greg.

Thanks for all you have done to guide me through the past 6 years without losing my mind. I am eternally grateful. Your writing is beautiful….and Happy Birthday.