Dear Reader,

On Friday night—early Saturday morning, Odessa time—our friend Zarina Zabrisky stayed up until the wee hours to join us on The Five 8. We wanted more details about the war crimes committed by Putin and his Russian occupiers in Ukraine, and she dutifully provided them. Her account was shocking to hear. At one point, after Zarina finished speaking, LB and I said, at the same time, one mumbled word: “Wow.”

For the last year, Zarina has been a war correspondent, intrepidly ranging across the battle-scarred parts of Ukraine to share with the world what’s really happening on the ground. She’s reported on the mass graves at Izium, the abduction and torture of residents in the occupied city of Kherson, and its subsquent liberation from the Russian orcs—and that’s just what she’s published at PREVAIL. Who can forget the footage of her visit to Chernobyl, where she toured the former nuclear reactor meltdown site?

While she has taken to her new job like a natural, Zarina is, at her core, a littérateur: novelist, short story writer, spoken-word artist, poet. Three years ago, she was hosting a YouTube book series where she interviewed writers from countries in the former Soviet Union. That’s who she is. That’s what she loves. Something she mentioned on the show has stuck with me all weekend: Putin did not just destroy swaths of Ukraine. He also, for her, destroyed Russian culture. How to savor Russian literature, as she always had, when Russia is now the universal enemy, a global pariah, author of all of this savagery, destruction, and woe? In particular, she said, she wanted to read one of her favorite works, the epilogue from War & Peace. The wisdom of Leo Tolstoy, with his deep knowledge of both the Napoleonic Wars and the human condition, is what she most missed.

I’ve read Anna Karenina, but not, I must confess, War & Peace. I started it three or four times, but never made it past the first chapter. It is a famously long book—part saga, part history, part philosophy—published in 1869, about the effect the tumultuous wars that happened a decade and a half before the author was born had on various Russian families.

For this week’s “Sunday Pages,” I’ve decided to go where Zarina wanted to, and share Tolstoy’s genius (a word he’d surely object to!). These excerpts are from the second, third, and fourth chapters of the first epilogue:

If we assume as the historians do that great men lead humanity to the attainment of certain ends—the greatness of Russia or of France, the balance of power in Europe, the diffusion of the ideas of the Revolution, general progress, or anything else—then it is impossible to explain the facts of history without introducing the conceptions of chance and genius. . . .

Why did it happen in this and not in some other way?

Because it happened so! “Chance created the situation; genius utilized it,” says history.

But what is chance? What is genius?

The words chance and genius do not denote any really existing thing and therefore cannot be defined. Those words only denote a certain stage of understanding of phenomena. I do not know why a certain event occurs; I think that I cannot know it; so I do not try to know it and I talk about chance. I see a force producing effects beyond the scope of ordinary human agencies; I do not understand why this occurs and I talk of genius.

To a herd of rams, the ram the herdsman drives each evening into a special enclosure to feed and that becomes twice as fat as the others must seem to be a genius. And it must appear an astonishing conjunction of genius with a whole series of extraordinary chances that this ram, who instead of getting into the general fold every evening goes into a special enclosure where there are oats—that this very ram, swelling with fat, is killed for meat. . . .

Here, Tolstoy pushes back on the fashionable “great men” theory of historical events, which says: Things are what they are, more or less static, and then an Alexander the Great or a Constantine the Great or a Peter the Great appears, does Great Things, and changes the course of history.

Bullshit, says Tolstoy. Great men are a product of their times—that is, of the random events that collectively shape history—and nothing more.

We need only confess that we do not know the purpose of the European convulsions and that we know only the facts—that is, the murders, first in France, then in Italy, in Africa, in Prussia, in Austria, in Spain, and in Russia—and that the movements from the west to the east and from the east to the west form the essence and purpose of these events, and not only shall we have no need to see exceptional ability and genius in Napoleon and Alexander, but we shall be unable to consider them to be anything but like other men, and we shall not be obliged to have recourse to chance for an explanation of those small events which made these people what they were, but it will be clear that all those small events were inevitable.

By discarding a claim to knowledge of the ultimate purpose, we shall clearly perceive that just as one cannot imagine a blossom or seed for any single plant better suited to it than those it produces, so it is impossible to imagine any two people more completely adapted down to the smallest detail for the purpose they had to fulfill, than Napoleon and Alexander with all their antecedents.

Alexander was tsar of Russia from 1801-1825, a period that encompassed the wars. Napoleon was Napoleon: upstart military man, megalomaniac, proto-strongman, and thirsty motherfucker—the Corsican Ron DeSantis. Here, Tolstoy writes about what his readers knew well: the European wars that began with Napoleon setting off eastward from Paris, conquering the lands he came across, and ended with him being chased back from whence he came after his spectacular blunder in Moscow. The author describes key events in Bonaparte’s life that his contemporaries would know as well as we do the story of Trump or Putin:

The fundamental and essential significance of the European events of the beginning of the nineteenth century lies in the movement of the mass of the European peoples from west to east and afterwards from east to west. The commencement of that movement was the movement from west to east. For the peoples of the west to be able to make their warlike movement to Moscow it was necessary: (1) that they should form themselves into a military group of a size able to endure a collision with the warlike military group of the east, (2) that they should abandon all established traditions and customs, and (3) that during their military movement they should have at their head a man who could justify to himself and to them the deceptions, robberies, and murders which would have to be committed during that movement.

And beginning with the French Revolution the old inadequately large group was destroyed, as well as the old habits and traditions, and step by step a group was formed of larger dimensions with new customs and traditions, and a man was produced who would stand at the head of the coming movement and bear the responsibility for all that had to be done.

A man without convictions, without habits, without traditions, without a name, and not even a Frenchman, emerges—by what seem the strangest chances—from among all the seething French parties, and without joining any one of them is borne forward to a prominent position.

The ignorance of his colleagues, the weakness and insignificance of his opponents, the frankness of his falsehoods, and the dazzling and self-confident limitations of this man raise him to the head of the army. The brilliant qualities of the soldiers of the army sent to Italy, his opponents’ reluctance to fight, and his own childish audacity and self-confidence secure him military fame. Innumerable so-called chances accompany him everywhere. The disfavor into which he falls with the rulers of France turns to his advantage. His attempts to avoid his predestined path are unsuccessful: he is not received into the Russian service, and the appointment he seeks in Turkey comes to nothing. During the war in Italy he is several times on the verge of destruction and each time is saved in an unexpected manner. Owing to various diplomatic considerations the Russian armies—just those which might have destroyed his prestige—do not appear upon the scene till he is no longer there.

On his return from Italy he finds the government in Paris in a process of dissolution in which all those who are in it are inevitably wiped out and destroyed. And by chance an escape from this dangerous position presents itself in the form of an aimless and senseless expedition to Africa. Again so-called chance accompanies him. Impregnable Malta surrenders without a shot; his most reckless schemes are crowned with success. The enemy’s fleet, which subsequently did not let a single boat pass, allows his entire army to elude it. In Africa a whole series of outrages are committed against the almost unarmed inhabitants. And the men who commit these crimes, especially their leader, assure themselves that this is admirable, this is glory—it resembles Caesar and Alexander the Great and is therefore good.

This ideal of glory and grandeur—which consists not merely in considering nothing wrong that one does but in priding oneself on every crime one commits, ascribing to it an incomprehensible supernatural significance—that ideal, destined to guide this man and his associates, had scope for its development in Africa. Whatever he does succeeds. The plague does not touch him. The cruelty of murdering prisoners is not imputed to him as a fault. His childishly rash, uncalled-for, and ignoble departure from Africa, leaving his comrades in distress, is set down to his credit, and again the enemy’s fleet twice lets him slip past. When, intoxicated by the crimes he has committed so successfully, he reaches Paris, the dissolution of the republican government, which a year earlier might have ruined him, has reached its extreme limit, and his presence there now as a newcomer free from party entanglements can only serve to exalt him—and though he himself has no plan, he is quite ready for his new rôle.

He had no plan, he was afraid of everything, but the parties snatched at him and demanded his participation.

He alone—with his ideal of glory and grandeur developed in Italy and Egypt, his insane self-adulation, his boldness in crime and frankness in lying—he alone could justify what had to be done.

He is needed for the place that awaits him, and so almost apart from his will and despite his indecision, his lack of a plan, and all his mistakes, he is drawn into a conspiracy that aims at seizing power and the conspiracy is crowned with success.

He is pushed into a meeting of the legislature. In alarm he wishes to flee, considering himself lost. He pretends to fall into a swoon and says senseless things that should have ruined him. But the once proud and shrewd rulers of France, feeling that their part is played out, are even more bewildered than he, and do not say the words they should have said to destroy him and retain their power.

Chance, millions of chances, give him power, and all men as if by agreement co-operate to confirm that power. Chance forms the characters of the rulers of France, who submit to him; chance forms the character of Paul I of Russia who recognizes his government; chance contrives a plot against him which not only fails to harm him but confirms his power. Chance puts the Duc d’Enghien in his hands and unexpectedly causes him to kill him—thereby convincing the mob more forcibly than in any other way that he had the right, since he had the might. Chance contrives that though he directs all his efforts to prepare an expedition against England (which would inevitably have ruined him) he never carries out that intention, but unexpectedly falls upon Mack and the Austrians, who surrender without a battle. Chance and genius give him the victory at Austerlitz; and by chance all men, not only the French but all Europe—except England which does not take part in the events about to happen—despite their former horror and detestation of his crimes, now recognize his authority, the title he has given himself, and his ideal of grandeur and glory, which seems excellent and reasonable to them all.

We might just as easily write a passage about the millions of chances that brought Putin to power in Russia, or Trump in the United States, or Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Ukraine: a middling KGB functionary, a money launderer turned reality TV star, a comedian, thrust into roles of vast historical significance. If we read any of those stories in a novel, we would not believe them. We could write much the same kind of stories for Hitler, for Stalin, for Churchill, for FDR, for Lincoln, for Obama.

But it is not just the individuals at the top; it is the thousands of people around them, the enablers, the cronies, the citizenry, who cede power to them, knowingly or not:

As if measuring themselves and preparing for the coming movement, the western forces push toward the east several times in 1805, 1806, 1807, and 1809, gaining strength and growing. In 1811 the group of people that had formed in France unites into one group with the peoples of Central Europe. The strength of the justification of the man who stands at the head of the movement grows with the increased size of the group. During the ten-year preparatory period this man had formed relations with all the crowned heads of Europe. The discredited rulers of the world can oppose no reasonable ideal to the insensate Napoleonic ideal of glory and grandeur. One after another they hasten to display their insignificance before him. The King of Prussia sends his wife to seek the great man’s mercy; the Emperor of Austria considers it a favor that this man receives a daughter of the Caesars into his bed; the Pope, the guardian of all that the nations hold sacred, utilizes religion for the aggrandizement of the great man. It is not Napoleon who prepares himself for the accomplishment of his role, so much as all those round him who prepare him to take on himself the whole responsibility for what is happening and has to happen. There is no step, no crime or petty fraud he commits, which in the mouths of those around him is not at once represented as a great deed. The most suitable fête the Germans can devise for him is a celebration of Jena and Auerstädt. Not only is he great, but so are his ancestors, his brothers, his stepsons, and his brothers-in-law. Everything is done to deprive him of the remains of his reason and to prepare him for his terrible part. And when he is ready so too are the forces.

Ah, but luck—which we can define, for our purposes here, as a preponderance of chances turning out in one’s favor—eventually runs out. The tide turns. From a literary standpoint, the story of Napoleon is fascinating because there really is one single moment when everything changes, like when a Pac-Man gobbles up the magic pill and can begin going after the ghosts: his catastrophically awful decision to invade Moscow.

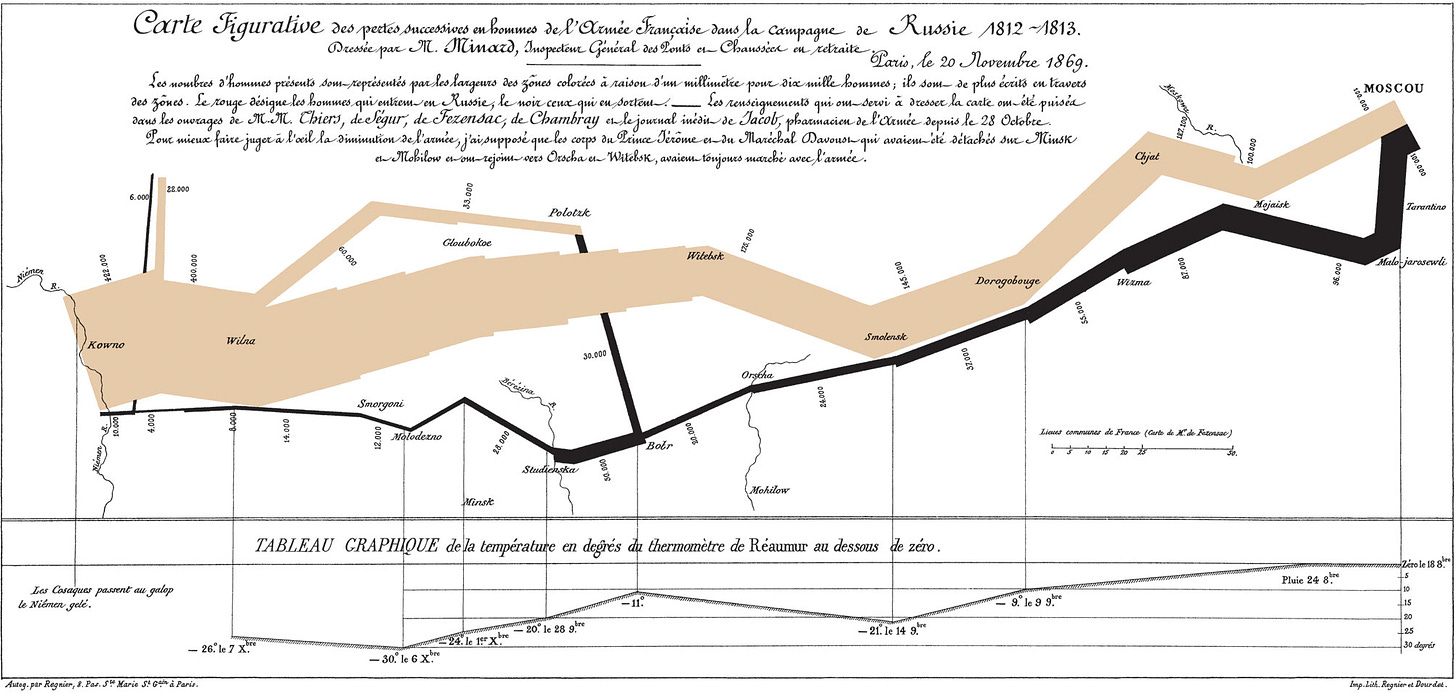

Charles Joseph Minard, a French civil engineer who pioneered the use of flow maps, designed a famous graphical chart showing the (decreasing) number of soldiers in Napoleon’s army going to and from Moscow, their movements by date, and—critically—how cold it got along the way:

This was the ultimate historical pendulum swing. And a lot of it was determined by the weather. Tolstoy continues:

The invasion pushes eastward and reaches its final goal—Moscow. That city is taken; the Russian army suffers heavier losses than the opposing armies had suffered in the former war from Austerlitz to Wagram. But suddenly instead of those chances and that genius which hitherto had so consistently led him by an uninterrupted series of successes to the predestined goal, an innumerable sequence of inverse chances occur—from the cold in his head at Borodinó to the sparks which set Moscow on fire, and the frosts—and instead of genius, stupidity and immeasurable baseness become evident.

The invaders flee, turn back, flee again, and all the chances are now not for Napoleon but always against him.

A countermovement is then accomplished from east to west with a remarkable resemblance to the preceding movement from west to east. Attempted drives from east to west—similar to the contrary movements of 1805, 1807, and 1809—precede the great westward movement; there is the same coalescence into a group of enormous dimensions; the same adhesion of the people of Central Europe to the movement; the same hesitation midway, and the same increasing rapidity as the goal is approached.

Paris, the ultimate goal, is reached. The Napoleonic government and army are destroyed. Napoleon himself is no longer of any account; all his actions are evidently pitiful and mean, but again an inexplicable chance occurs. The allies detest Napoleon whom they regard as the cause of their sufferings. Deprived of power and authority, his crimes and his craft exposed, he should have appeared to them what he appeared ten years previously and one year later—an outlawed brigand. But by some strange chance no one perceives this. His part is not yet ended. The man who ten years before and a year later was considered an outlawed brigand is sent to an island two days’ sail from France, which for some reason is presented to him as his dominion, and guards are given to him and millions of money are paid him.

Read that last part again. After his first defeat, Napoleon—author of years of horrific wars across the continent that spilled across the globe; an outsider with no legitimate claim to rule anything—should have appeared to them [as] an outlawed brigand. But by some strange chance no one perceives this. His part is not yet ended. Does this not sound like someone we recognize? A certain lifelong criminal who should have always been perceived as such, but who remains at large, and beloved in certain benighted circles, holding rallies in Texas cities where mass cult suicides occurred? Millions of money are paid to him.

Like Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees, Napoleon kept coming back. People had fallen too completely under his spell for it to wear off suddenly, despite his ample failures. Tolstoy continues:

The flood of nations begins to subside into its normal channels. The waves of the great movement abate, and on the calm surface eddies are formed in which float the diplomatists, who imagine that they have caused the floods to abate.

But the smooth sea again suddenly becomes disturbed. The diplomatists think that their disagreements are the cause of this fresh pressure of natural forces; they anticipate war between their sovereigns; the position seems to them insoluble. But the wave they feel to be rising does not come from the quarter they expect. It rises again from the same point as before—Paris. The last backwash of the movement from the west occurs: a backwash which serves to solve the apparently insuperable diplomatic difficulties and ends the military movement of that period of history.

The man who had devastated France returns to France alone, without any conspiracy and without soldiers. Any guard might arrest him, but by strange chance no one does so and all rapturously greet the man they cursed the day before and will curse again a month later.

This man is still needed to justify the final collective act.

That act is performed.

The last rôle is played. The actor is bidden to disrobe and wash off his powder and paint: he will not be wanted any more.

And some years pass during which he plays a pitiful comedy to himself in solitude on his island, justifying his actions by intrigues and lies when the justification is no longer needed, and displaying to the whole world what it was that people had mistaken for strength as long as an unseen hand directed his actions.

The manager having brought the drama to a close and stripped the actor shows him to us. “See what you believed in! This is he! Do you now see that it was not he but I who moved you?”

But dazed by the force of the movement, it was long before people understood this.

May the people of the world see our contemporary Napoleons for the outlawed brigands that they are. Let Waterloo come for Putin and for Trump. Let Zarina enjoy her Tolstoy again.

ICYMI

The full episode featuring Zarina Zabrisky:

Photo credit: Nicolas-Antoine Taunay. “Bonaparte reçoit les prisonniers sur le champ de bataille,” 1797.

My head just exploded! What island(s) would you recommend for our Napoleons? They need to be separate IMO, and far from any mainland, so as to preempt any collusion!

BTW, I have this old people's flirtation with memory. I remind myself the Thursday before to watch Five/8 early Saturday morning (circa 2:00 a.m.) Before I realize it, it's Sunday morning and I've yet to watch. I will go there now to listen to the lovely Zarina Zabrisky...a particular shero of mine.

As always, many thanks, Greg Olear.

I always love your Sunday Pages but this week is so potent, so personal. Thank you.

I studied Russian Language, Literature, History and Political Science. I was so fascinated by the difference between the American character and the Russian character. I loved the "big baggy monsters" of Russian Literature. I loved Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Chekhov. My love for the Russian character was cultivated during the end of the cold war and the things I saw happening there are definitely being mirrored here. My hope is that we as a people will remember that again and again we have stood for Freedom. That we come from people who stood against authoritarian rule...

May we remember to be free we all must be free