The Writer and the Whistleblower

A discussion with the novelist, biographer, essayist, and distinguished writer in residence Francine Prose, author of the new memoir, "1974: A Personal History"

Whistleblower stories rarely have happy endings. Tony Russo’s was no exception.

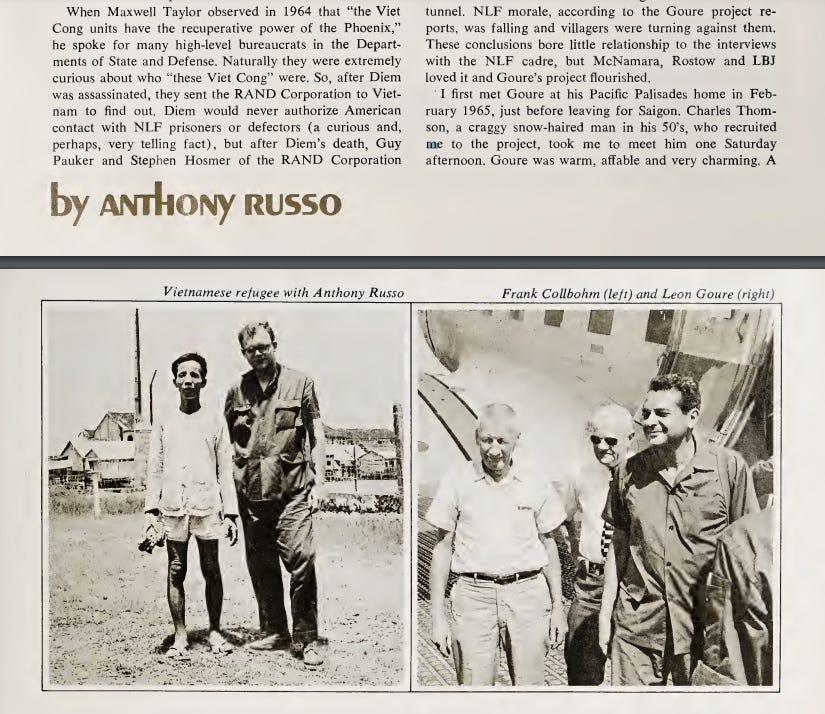

Russo worked for the RAND Corporation. He’d been to Vietnam. He met with Leon Gouré and the other policymakers, saw how out of touch they were with the Vietnamese people. He discovered that the U.S. military was torturing Viet Cong prisoners. He became radicalized against the war. He cultivated his friendship with Daniel Ellsberg, a fellow RAND employee, and convinced him to steal what became known as the Pentagon Papers. He figured out where to make copies of the thousands of pages of the documents. He was indicted, along with Ellsberg, under the Espionage Act. His effect on history was incalculable.

The Pentagon Papers revealed systematic mendacity by a parade of presidents of both political parties. Truman gave military support to the French colonizers, and lied about it. Eisenhower began a covert operation to thwart the Communist government of North Vietnam, and lied about it. Kennedy expanded that operation, and lied about it. Johnson planned full-scale war operations, and lied about it—and continued bombing the region despite evidence that the tactic was not working. For years, the government lied about Vietnam, and Russo was one of the whistleblowers, perhaps the most critical one, who exposed those lies.

But by 1974, Russo was already, at 38 years old, on the road back to obscurity. Watergate overshadowed the leak of the Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force. His case was thrown out of court, ending a lot of the public interest. Ellsberg—handsome, polished, TV friendly—was now the face of the Pentagon Papers, the George Michael to Russo’s Andrew Ridgeley. Worst of all, Russo’s efforts had been in vain. The war had not ended. Nixon had been re-elected in a landslide; he and Kissinger kept merrily row-row-rowing the same sinking boat, and American soldiers and Vietnamese nationals continued to die.

In the winter of 1974, Russo was living in San Francisco. He spent his evenings driving aimlessly around the city, taking the hills way too fast. He met a woman, ten years younger, whom he’d take along on these rides. He would talk and talk and talk. And she would listen.

As luck would have it, Russo chose his companion wisely. Sitting next to him in the car, hanging on every word he said, was none other than Francine Prose—then a first-time novelist, now one of the finest and most accomplished writers we have. It is one of those inexplicable twists of fate that brought the two of them together, half a century ago.

By 1974, “Ellsberg was kind of celebrity, which Tony wasn’t,” Prose, my guest on today’s PREVAIL podcast, tells me. “They’d taken all these risks, and it was not exactly clear what they’d accomplished or what had happened. And Tony, I mean, now he’s—as far as I can tell, he’s not even part of the story anymore.”

This is true. Last night, I read about the Pentagon Papers on half a dozen websites. Russo is barely mentioned. Here’s how the Miller Center, the nonpartisan group that focuses on the presidency, references him (boldface mine): “Over the course of several weeks in the fall of 1969, Ellsberg managed to sneak out and photocopy the study with the help of another former RAND employee.”

“When you look at the news photos from the time,” Prose tells me, “he’s standing right next to Ellsberg…when the reporters are talking to him outside the courtroom. But then, little by little, because of who he was—Ellsberg was handsome and married to an heiress, and rich, presentable, and a political moderate. And Tony was a…left-wing ideologue really, a zealot, and shaggy and sort of unkempt—and always a little off, I think. So it was easy to kind of write him out of the story.”

Prose has taken it upon herself to write him back in. 1974: A Personal History, Prose’s new book, is her first memoir. She tells the story of her time with Russo, so the book is about the famous-but-less-famous-than-Ellsberg whistleblower, but it’s also about her—about being a young writer, about navigating the often melancholy period of time when we are in our twenties, about San Francisco, about art and literature and politics, about what has changed and what has stayed the same. It’s a wonderful book, beautifully written, compelling and smart and, above all, moving; reading it, I felt privileged to hear about what happened and take in the wisdom she acquired from her experiences. 1974 is a gift.

“I wanted to feel like an outlaw,” she writes, and,

I wanted to feel the thrill of not knowing or caring where I was going or what I was supposed to be doing. The dream-like unreality of those high-speed drives was nerve-racking but weirdly relaxing. Nothing was expected of me. I didn’t have to think. I hardly had to speak. All I had to do was listen.

Writers are typically good listeners, and Prose is one of the best. 1974 is proof of that.

During our discussion, I asked her what Tony Russo, who died in 2008, would have made of today’s chaotic political landscape: the rise of Trump, the fascist MAGA movement, and so on.

“I don’t think it would have surprised him,” Prose tells me. “I think it would have seemed like a continuation of things that he’d seen….The people who are making—you know, what we used to call the military industrial complex: they haven’t gone away.”

“I think he would have been disappointed, because like all activists, he was an idealist,” she says. “But I don’t think he would have been surprised.”

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

S7 E22: 1974: The Writer and the Whistleblower (SEASON FINALE, with Francine Prose)

Francine Prose is the author of over 30 books. Her 12 novels include My New American Life, A Changed Man and Blue Angel, a finalist for the National Book Award. Her nonfiction works include the indispensable Reading Like a Writer; Caravaggio: Painter of Miracles; and The Lives of the Muses: Nine Women and the Artists They Inspired, a New York Times Notable Book for 2002. She’s a contributing editor at Harper's, and her essays, reviews, and criticism have appeared in New York Times Book Review, Wall Street Journal, and The Guardian, among other publications. She’s a past president of PEN America, a distinguished writer in residence at Bard College, and a recipient of the 2008 Edith Wharton Achievement Award for Literature. Her latest book—and first memoir—is called 1974: A Personal History.

In this conversation, Greg Olear talks to Francine Prose about her new memoir, 1974. They discuss the challenges of writing about oneself, the impetus for the book, Tony Russo and the Pentagon Papers, whistleblowers, “Vertigo,” the role of literature in society, the bias against women writers, the state of fiction writing, the impact of AI, the dangers of self-censorship, the current political climate, and more.

Plus: a new Zoom!

Buy her book:

https://www.harpercollins.com/products/1974-francine-prose?variant=41105435459618

Her Facebook page:

https://www.facebook.com/FrancineProseAuthor/

Her Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/prose.francine/

Note: This is the finale of the 7th season of PREVAIL. I will return for Season 8 on September 6th.

Photo credit: A page from “Ramparts” magazine, November, 1972 (the month and year I was born!).

So many good books, so little time!

"Life isn't a matter of milestones but of moments." Rose Kennedy.

Francine Prose is to be admired. She took moments and turned them to milestones. As this Old Man looks back, I wonder how many moments I missed the significance of, they just passed me by. Those who can truly appreciate the value of a moment and turn it into something remarkable are to be admired. For many of us a moment is something to get behind us as we chase the next moment. It is truly sad that we couldn't or wouldn't savor the moment.

Enjoy your break, perhaps something momentous will occur.