Who Owns Kavanaugh #2: The Financials & The Red Flags

Part two of the series examines Brett Kavanaugh's finances, which don't add up.

This series is written by Greg Olear in collaboration with LB (@LincolnsBible).

Part One is here.

Prologue: Take Me Out to the Ballgame

Oh my God, these seats…right behind home plate. And it’s Game One of the Division Series—Cubs versus the 97-win Nationals, Strasburg on the mound. A collective childhood fantasy for the four middle-aged friends was happening. The adrenaline of a dream come true was almost as sweet as the smell of the freshly-cut grass, on this perfect October night at the ballpark.

Each of the four friends had enjoyed these seats before, many times, thanks to their buddy, Brett Kavanaugh. But tonight seemed extra special. They spent the evening cheering on Harper and Rendon, munching gourmet food in the VIP dining area, and popping in and out of the executive suite that comes with the season tickets—their thirst for this elite slice of Americana quenched, inning by inning, with delicious, ice-cold beer. Ahh…Nationals Park. The exorbitant cost of the evening was worth every hard-earned penny they’d each spent. Tonight, they had a memory so special, they wouldn’t need to mark the date in a calendar to remember every sight, taste, and sound.

That’s Brett’s story, and it’s a pleasant one. We just don’t know that any of it is true.

We don’t know for certain if he actually purchased seasons tickets to the Washington Nationals every year from 2005 to 2017.

We don’t know if he held a “ticket draft” in his kitchen, where his friends—some from high school—would pull names out of Ashley’s crockpot to see who got which seats.

We don’t even know if Brett even likes the Nationals, who played in Montreal from 1969 to 2004, or if he, himself, ever attended a game.

Unlike the cold hard math of baseball, the story Brett told about these tickets just doesn’t add up.

Still, one can easily imagine the pull of an evening like that—the dream of a perfect night at the ballpark. The promise of it might even compel mature, middle-aged men to tolerate a continued friendship with a painfully immature man like Brett.

But not everyone who knew Brett from high school was so tolerant. At least one person was horrified. By 2018, she was a professor of psychology at Palo Alto University, and a research psychologist at the Stanford University School of Medicine. She specialized in designing statistical models for research projects. Her name was Christine Blasey Ford.

On July 30, 2018, Ford sent a letter to the office of her Senator, Diane Feinstein, detailing a sexual assault that happened to her at a party in high school, at the hands of Brett Kavanaugh and his friend, Mark Gavreau Judge. With great trepidation, she sent the email, and she waited. And for weeks...nothing happened.

I. THE FINANCIALS

In the lead-up to Brett Kavanaugh’s 2018 Senate confirmation hearing, an epic fight was brewing. Nearly half a million pages of documents had already been released to the Committee, out of which 150,000 thousand or so were confidential. The White House was refusing to release over 100,000 more. Democrats were furious, but they were in the minority. They couldn’t stop Mitch McConnell from ramming this guy through, with nothing but shadows around him. All they could do was make a stink.

Then, just hours before the first hearing on September 4, the White House dumped another 42,000 pages of documents, with strict instructions that they remain confidential. In totality, it was an impossible amount of documentation to properly wade through. And all of it was in addition to the complex web of Kavanaugh’s financial documents that sat atop the Senators’ plates.

While the White House releases came with confidentiality restrictions, Brett’s financials were public. Most of this is due to judiciary financial transparency rules, since Kavanaugh was already a federal appeals judge. The press could get their hands on his financial disclosure statements.

From his nomination in July to his hearing in September, we were deluged with articles about Brett’s money. The reporting raised more questions than it answered. There were massive credit card debts that were suddenly, inexplicably paid off. There was a mystery around his million-dollar mortgage. There were stories about baseball tickets and patterns of expenditure that raised the specter of a gambling habit. There was a lifestyle that did not match an income. We produced a deep dive on Medium at the time, where we pulled at most of the financials that didn’t add up, including some home repairs. What should have been an exercise in basic math remained a morass—spread out in pieces from one print article to the next.

By the time any of it could be explored by the Judiciary Committee, none of it mattered. We never got our answers. It’s our hope that by putting all of the pieces together, in one place, the questions that most need answering can come into sharp focus. And the answers will have the space to emerge.

After all, it’s just math.

The Big Buy

Since Robert Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court was torpedoed in 1987, the confirmation of a SCOTUS nominee has involved a healthy amount of theater. Usually, a qualified candidate is nominated, goes through the interview process, is the subject of grandstanding by the more partisan Senators, and is then confirmed. That’s what happened with Neil Gorsuch.

But Brett Kavanaugh was different. His entire confirmation process was carefully stage-managed—not unlike how studios woo Academy members to vote for their films. There were ads. His face was on the side of a bus. IRS documents obtained by TMI show that a dark money group raised almost $30 million in the fiscal year when Kavanaugh was nominated—specifically, the Judicial Crisis Network (JCN), the PR arm of Leonard Leo’s operation discussed in Part One of this series. More than half of that $30 million came from a single anonymous donor. One individual, whose identity we do not know, donated over $15 million bananas to help install this guy on the Court.

To be clear, this is not illegal. But it is unusual. Very wealthy people, whose identities remain a mystery, spent vast amounts of money to ensure that their boy, Brett Kavanaugh, made it to the finish line. You don’t pony up that much cash and not expect a significant return on your investment.

What we know: A single donor gave $15 million to JCN in 2018, helping promote Brett’s nomination.

What we don’t know: The donor’s identity.

The Mortgage

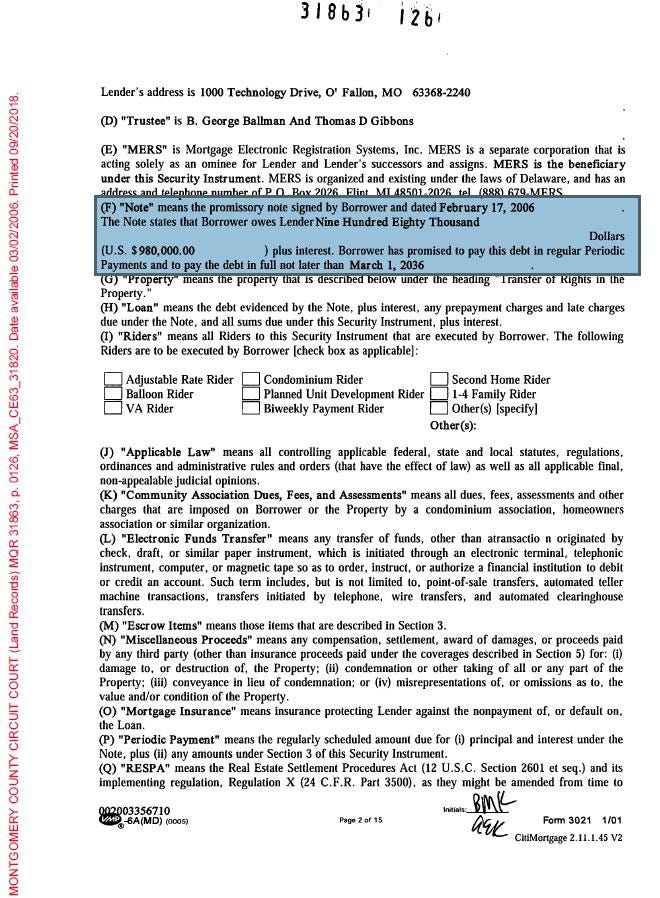

In 2006, at the height of the real estate bubble—and three months before his first Senate confirmation hearing—Brett and Ashley Kavanaugh purchased a home in Chevy Chase, Maryland, the tony Washington suburb where he’d grown up. The handsome four-bedroom had a purchase price of $1,225,000—a cool half a million dollars more than the sellers had paid six years earlier. The initial mortgage on the property was for just under a million dollars:

According to his financial disclosure statements, the Kavanaughs’ total stated assets at the time of the loan came to $121,000, with the bulk of that being “vehicles and other personal property.” Meanwhile, they carried $25,000 in credit card debt. Their net worth was $96,000 ($121k in assets less $25k in liabilities).

We’re writers, not mathematicians, but we’re pretty sure that $96,000 is a lot less than the $245,000 he produced for the down payment. And we’re not the only ones who can add and subtract. Senate Democrats were also on top of this. When asked about it during his 2018 Senate questioning, here’s what Kavanaugh said:

The Thrift Savings Plan loan that appears on certain disclosure reports was a Federal Government loan to help with the down payment on our house in 2006. That government loan program is available for federal government workers to help with the purchase of their first house. In our case, that loan was paid back primarily by regular deductions from my paycheck, in the same way that taxes and insurance premiums are deducted from my paycheck. That loan has been paid off in full.

What Brett proposes here is what Kellyanne Conway might term “alternative math.” In 2005, a year before he bought the house, Kavanaugh disclosed that the total value of his Thrift Savings Plan account was $70,000—less than a third of the $245,000 down payment.

So, like, where’d the money come from?

Not his day job. At the time of the home purchase, Brett was a federal employee, drawing an annual salary of $62,026. Ashley worked at the George W. Bush Presidential Library Foundation and the Community Foundation for National Capital Region, neither high-salaried positions. Her retirement plan was worth $1,000. There was no other income, and no gifts reported. Nor did they cash in stocks or other investments. At least, that’s what he told the Senate.

The earth is round. Two plus two equals four. And the “Thrift Savings” story is bullshit.

Lifestyle

If it was just the down payment, maybe we could chalk it up to divine intervention. But it’s not only that he came up with a big chunk of change, it’s that he didn’t make enough money to even BEGIN to cover his family’s expenses.

At four percent interest, the mortgage payments on his house would have been $4,600 a month, or $55,200 a year. In other words, the mortgage payments alone were more than what Brett Kavanaugh took home in 2006 after taxes. Just the mortgage. That doesn’t include property taxes, homeowners insurance, or maintenance costs—the last of which, as he painstakingly explained in his Senate written testimony, cost a pretty penny:

Over the years, we have sunk a decent amount of money into our home for sometimes unanticipated repairs and improvements. As many homeowners probably appreciate, the list sometimes seems to never end, and for us it has included over the years: replacing the heating and air conditioning system and air conditioning units, replacing the water heater, painting and repairing the full exterior of the house, painting the interior of the house, replacing the porch flooring on the front and side porches with composite wood, gutter repairs, roof repairs, new refrigerator, new oven, ceiling leaks, ongoing flooding in the basement, waterproofing the basement, mold removal in the basement, drainage work because of excess water outside the house that was running into the neighbor’s property, fence repair, and so on.

Basically, the Kavanaughs paid one-point-two for a money pit. Why would any bank with a functional abacus approve such a terrible loan? And why would Brett and Ashley agree to it?

To compound this profile, the Kavanaughs are also members of a country club with a $92,000 initiation fee and $9,000 annual dues, and send their two daughters to a private school that costs a minimum of $20,550 for their annual tuition. So, like, how could they afford all of that?

What we know: Based on their earnings, Brett and Ashley could not afford their down payment, monthly mortgage, and fixed expenses.

What we don’t know: Where the down payment came from, and how they were able to pay the mortgage.

What it COULD be: In the case of the home & mortgage anomalies, there may be an answer. And it spells trouble…

Kavanaugh’s family is well-to-do. His father, Everett Edward “Ed” Kavanaugh, Jr., was a well-heeled corporate lobbyist for what used to be called the Toilet Goods Association. As Salon reports:

For more than three decades…Everett Edward Kavanaugh worked for the Cosmetic, Toiletry, and Fragrance Association (CTFA), now called Personal Care Products Council (PCPC), whose 600 member companies include giant multinational firms like J&J, Aveda, Clairol, L’Oréal, and Unilever. Once known inelegantly as the Toilet Goods Association, the name change (to CTFA) in 1971 was part of “an organizational ‘metamorphosis’ that prepared the association, and the industry to face a new decade of challenge.”

The year before Brett and Ashley bought the house, 64-year-old Ed Kavanaugh retired from his position at the CTFA, receiving a farewell package worth some $13.5 million. So Pops definitely had a lot of money burning a hole in his pocket, if he decided to bankroll the life of his only child and his family. But, as with all things Kavanaugh, even this benign explanation is a Devil’s Triangle of logic.

If Megabucks Ed was underwriting his son’s life, why just give the down payment? Why not buy the house outright? Then it becomes an investment. Why involve a lender at all?

And if Brett did receive such significant assistance from his parents, why didn’t he just say so? Surely there is no shame in accepting family help—especially if you have forsaken corporate lobbying, with its filthy lucre, for a career in public service. Was he concerned about the tax implications? Was he embarrassed that his buddies were all rolling in dough, and he was too broke-ass to afford a new car? Was the humiliation so great that, oops, he omitted the gift on his federal disclosure statement?

Whatever the case, the explanation Kavanaugh gave, under oath, about the provenance of his money is simply not corroborated by the evidence. Once again, we are asked to believe “alternative math.”

The Debt

The unaccounted-for quarter-mil down payment was not the only whopper in his financial disclosure forms. Brett’s credit card debt was also an issue. Kavanaugh’s 2016 statement shows significant credit card balances on three cards: Chase, Bank of America, and USAA; the overall debt amount increased from the previous year. According to his disclosure form, the minimum he would have owed in combined credit card debt was $45,003; the real number is almost certainly higher.

A year later, POOF, all of that credit card debt was gone.

Nothing in the disclosure statements gives the faintest hint at how this was achieved.

When asked about being suddenly and inexplicably back in the black, Kavanaugh said:

Our annual income and financial worth substantially increased in the last few years as a result of a significant annual salary increase for federal judges; a substantial back pay award in the wake of class litigation over pay for the Federal Judiciary; and my wife’s return to the paid workforce following the many years that she took off from paid work in order to stay with and care for our daughters. The back pay award was excluded from disclosure on my previous financial disclosure report based on the Filing Instructions for Judicial Officers and Employees, which excludes income from the Federal Government.

This statement is not a lie, per se, but it does skirt the truth. First, while his family income did increase, the Kavanaughs, as discussed, simply did not generate enough to cover their ample expenses. Second, Ashley Kavanaugh went back to work in 2016, a year when their credit card debts went sharply up, not down. Finally, the “substantial back pay award” for the Federal Judiciary—approximately $150,000 before taxes—was issued in 2014. While this squares with his financial disclosure statement of 2015 (which shows a sharp reduction in outstanding credit card balances), the overall picture remains one of a family mired in debt, given an infusion of unexpected cash, and still struggling to make ends meet.

Let’s return to a plausible explanation for the sudden clearing of his credit card debt: Daddy Ed-bucks. If the windfall of money to make Brett whole came from his wealthy father, why did he fail to mention Ed Kavanaugh in the disclosures? Gifts of that magnitude must, by law, be accounted for. There is a special section for it on the forms.

“If it was a debt owed by someone else, he should have disclosed the debtor by reporting a receivable in the assets/income section of one report,” explains Walter Shaub, who headed the U.S. Office of Government Ethics for the Obama Administration. “If the payoff was a gift, he should have reported the payor in the gifts section of the next report.”

Kavanaugh did neither.

What we know: Per his 2017 financial disclosure—filed in May of 2018—Brett Kavanaugh, on his modest salary as a federal judge, managed to pay off $45k+ in credit card debt.

What we don’t know: How?

II. THE RED FLAGS

What are the odds that Brett Kavanaugh has a gambling problem? Rumors of his yen for the sports book followed him to the Senate Judiciary Committee, which grilled him on the subject. Under oath, he denied ever reporting gambling losses or gambling earnings on his tax forms, and—here is the potential doozy—claimed never to have participated “in any form of gambling or game of chance or skill with monetary stakes, including but not limited to poker, dice, golf, sports betting, blackjack, and craps” since becoming a federal judge in 2006.

We have no way of knowing if Kavanaugh is a high-stakes gambler, and we’re not accusing him of being one. However, given the murkiness surrounding the sudden influx of capital into his pocket, it is not unreasonable to ask if that huge down payment was a windfall from some crazy parlay he’d won. Same thing with the magical vanishing credit card debts.

In talking with professional bookies about this, we are informed that he fits the profile: his personality, his love of sports, and the boom-or-bust nature of his financial statements. “You look at the spots Kavanaugh has gotten himself into,” says a PREVAIL source, who operates in the colorful world of professional gambling, “and it’s either drugs, women, or gambling. It doesn’t look like the first two.”

And then there is the weirdness about the baseball tickets. This is where Brett Kavanaugh, a man mired in debt on three different credit cards, agreed to be the guy who purchased Washington Nationals season ticket packages for all of his pals, who then reimbursed him for their share.

When asked about Kavanaugh’s hefty liabilities in 2018, White House spokesman Raj Shah told Amy Brittain of The Washington Post that “Kavanaugh built up the debt by buying Washington Nationals season tickets and tickets for playoff games for himself and a ‘handful’ of friends. Shah said some of the debts were also for home improvements.” Shah explained that Kavanaugh’s “friends” reimbursed him for said tickets, but did not identify who these “friends” were. Further, Brittain writes: “Shah said the payments for the tickets were made at the end of 2016 and paid off early the next year. ‘He did not carry that kind of debt year over year,’ Shah said.” (Shah has since moved on to FoxNews, where as a VP executive, he can lie with impunity).

In other words, the reason Brett’s credit card debt went from $45,000+ to zero from 2016 to 2017…is that he and his friends went in on some MLB tickets? Really?

On its face, this explanation is absurd. First, as his financial disclosure statements make clear, Kavanaugh did, in fact, “carry that kind of debt year over year.” Second, given his enormous fixed monthly expenses and his country-club lifestyle, he couldn’t afford even his share of the tickets. Third, for Brett to be the purchaser of the tickets is financially reckless. If you add big purchases to credit cards that are already carrying large balances, you increase the principal on which the credit card company charges interest. Why would Kavanaugh offer to front the cash for the tickets—and why would he do it across three credit cards? Does he really like the Nationals that much? Does anyone?

Here’s what he told the Senate:

As is typical with baseball season tickets, I had a group of old friends who would split games with me. We would usually divide the tickets in a “ticket draft” at my house. Everyone in the group paid me for their tickets based on the cost of the tickets, to the dollar. No one overpaid or underpaid me for tickets. No loans were given in either direction.

As with his responses to questions about the down payment, this “ticket draft” story doesn’t pass the smell test. It’s dumb. And, by giving it to the Senate, it opened the door for more scrutiny—more questions over why he would do this? The Senate Democrats never got to pursue the reasons. We’ll give it a shot:

Being eternally short on funds, maybe the tickets were a way to get some cash in Brett’s pocket? This is the extravagant version of going out with your buddies, putting the $100 bar tab on your AMEX, and collecting $20 from your four friends. It’s like hitting an ATM machine. We’ve all done it. And now we get to call it “The Kavanaugh.”

PREVAIL contributor Moscow Never Sleeps, an attorney, has a saltier theory:

Kavanaugh’s story is that he ran up between $60-200k in credit card debt buying baseball tickets. That is a traceable fact, if anyone had access to his card statements, or to the ticket sales office of the Nationals.

The next part of his story is that he distributed those tickets and was reimbursed for them; thus he paid off the credit cards. As long as he has about seven to 21 alibis willing to say, “Yeah, I boofed Brett about nine grand in cash for my set of tickets,” that explains (a) how he got the money back, (b) why there’s no paper trail, and (c) how there’s no tax filings for receipt of 10k or more in cash from one particular source.

Of course, the actual amount of cash he gets is (potentially) a lot more. But since the main flagship questions—why did he buy the tickets and how did he afford to pay for them—are now answered with full legal plausibility, it’s nearly impossible to claim probable cause for a warrant to look for more cash coming in than going out.

So, presto, you now have (a) washed a transfer of between 60-200 thousand dollars to a government official in one year and (b) fairly well immunized that government official, absent completely new evidence from a warrant on his finances that would discover the other quarter million you (potentially) “boofed” him.

To be clear: that is just a theory. We have no proof that Kavanaugh did something like that, and we’re not accusing him of doing so. But the pesky fact remains: in order to finance his handsome home and underwrite his family’s expensive existence, he had to be getting cash from somewhere.

What’s also indisputable is that Kavanaugh’s two unexplained financial windfalls immediately preceded his nomination to 1) the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals (mortgage down payment, 2006) and 2) the Supreme Court (credit card debts, 2017). There may be a perfectly benign explanation for that, but “baseball tickets” ain’t it. Optically, this is fishier than a tureen of beluga caviar. What it looks like is that this guy has been paid off. What it looks like is that he’s owned.

The purpose of financial disclosure, as Kavanaugh himself has pointed out, is to identify potential conflicts of interest. These conflicts tarnish a judge’s impartiality, which is the most essential qualification for the job. If a sitting Supreme Court Justice is beholden to unknown creditors, we need to know who they are (even if the unknown creditors turn out to be Ma and Pa Kavanaugh). How else can we be sure he isn’t compromised?

“[W]e still don’t know who paid off Kavanaugh’s massive debts because he was allowed to violate the financial disclosure law,” Shaub, the former head of the Office of Government Ethics, tweeted in January 2021, “and no one made an issue of it during his confirmation hearing.”

Watching those hearings now, from that first week of September, 2018, it seems clear to us that the Democrats had a strategy for getting everything out. And frustration was building, because they had also been analyzing that massive, last-minute document dump from the White House—and Brett’s under-oath testimonies, both in 2006 and concurrent with the dump in 2018, were not checking out.

So, Corey Booker placed a big bet. On September 6, he released the confidential documents. There was a flurry of activity, because now the press could go through all of Brett’s secret correspondence.

And just as the earliest stories were beginning to surface, the shit hit the proverbial fan. A curveball from left field was thrown over the plate. For the first time since the Clarence Thomas hearings in 1989, the nominee was being accused of a sex crime—sexual assault, in the case of Brett Kavanaugh. And all hell broke loose.

Someone had finally read Dr. Ford’s email.

All that credit card debt went poof and yet no one in the GOP blinked an eye. I recall Lindsey being really mad at I-like-beer man’s confirmation hearing. What does he know? If there’s one thing I’ve learned from @lincolnsbible early, early on it’s FOLLOW THE MONEY!!!

Another really great article, you guys. Love you bunches! Thank you for all you do.

MUCH better than my favourite Saturday matinee of all those years ago, "The Green Arrow": we leave this episode with the spikes in the dungeon ceiling moving slowly downwards .. :D

But: "One individual, whose identity we do not know, donated over $15 million bananas to help install this guy on the Court. To be clear, this is not illegal." Good grief ! - WHY is it not illegal ? I will never be able to understand most of your laws ..