Dear Reader,

“You’re empty-nesters now,” people invariably remark. “What’s that like for you?”

Ten days into empty-nestery, the answer is: exhausting. Mentally, emotionally, and most of all physically exhausting. As it turns out, moving two humans into two different dorms on two different campuses in two different states over the course of three days involves a lot of actual, you know, moving. Stuff is heavy. August is hot. Driving wears you out.

Not only that, but I’ve spent most of my free time since the chickens flew the coop cleaning, sorting, hauling furniture, moving stuff around, and throwing stuff away. It took until Friday, right before The Five 8 started, to get the house back to (the new) normal—just in time for the kids to return for the long weekend.

So there hasn’t been much time for exhalation, let alone philosophical musings about Life and The Passage of Time and Getting Older. But I can feel those unwelcome eschatological thoughts gathering outside the door, like a fog, like a darkness, patiently waiting to be reckoned with. The darkness always wins, in the end. Because darkness is the natural state of things. After all, God didn’t create darkness, as the Book of Genesis makes clear; the darkness was already there, has always been there: the backdrop of all His creations, the bottommost layer of the infinite Photoshop file that is the universe, the black-box theater upon whose stage every human that ever drew breath has strutted and fretted his hour.

Nabokov, in Speak, Memory: “The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.” One of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s figs: “My candle burns at both ends; It will not last the night; But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—It gives a lovely light!” And the epiphany of the dying Babe Paley at the end of Capote vs. The Swans, which we finished watching this week: “I learned that you cannot possess the light. But you can touch it.”

No flame is eternal. The darkness always wins, in the end.

This admittedly gloomy take gives new meaning to the expression passing the torch—and let me tell you, there are few moments in life that feel more like passing the torch than dropping off both your kids at college. Although another torch-passing moment does spring to mind. . .

My father died on New Year’s Eve 2022, six weeks and six days after my fiftieth birthday. He was 74. His father died at 70. One of the first thoughts I had after he passed was, “Well, I have another 25 years left.” Twenty-five years is a long time, but in the grand scheme of things, it is nothing—the briefest crack of light.

Lately I have been struggling to remember things. Names, dates, sequences of events, gossip, the geometry of which friend doesn’t like which other friend and why, entire experiences in the pre-kids period of 2000-2005 that my wife recalls almost eidetically, who I owe an email to. Sometimes I find myself stammering when I speak, as if the thoughts in my brain are constipated. When I graduated from college, I wrote in chalk on my mortarboard what was the title of my first attempt at writing a novel, a title derived from a “Far Side” comic: MY BRAIN IS FULL. How empty it was then! I still had room enough on my internal hard drive for calculus and French conjugations and proper spelling and hours, days, weeks worth of Simpsons quotes.

I have always relied on my memory—it got me through high school and college unscathed—and it’s unsettling to feel it degrade, like the velocity on an aging pitcher’s fastball. Understand, this isn’t some rare medical condition. I have thrown too many innings, is all. But the series is too important, the stakes too high, to rest my arm now. The old baseball saying has especial resonance as we enter the home stretch leading to Election Day: We can sleep in November. (We will, and soundly!)

What do we do to honor someone’s memory? We light a candle.

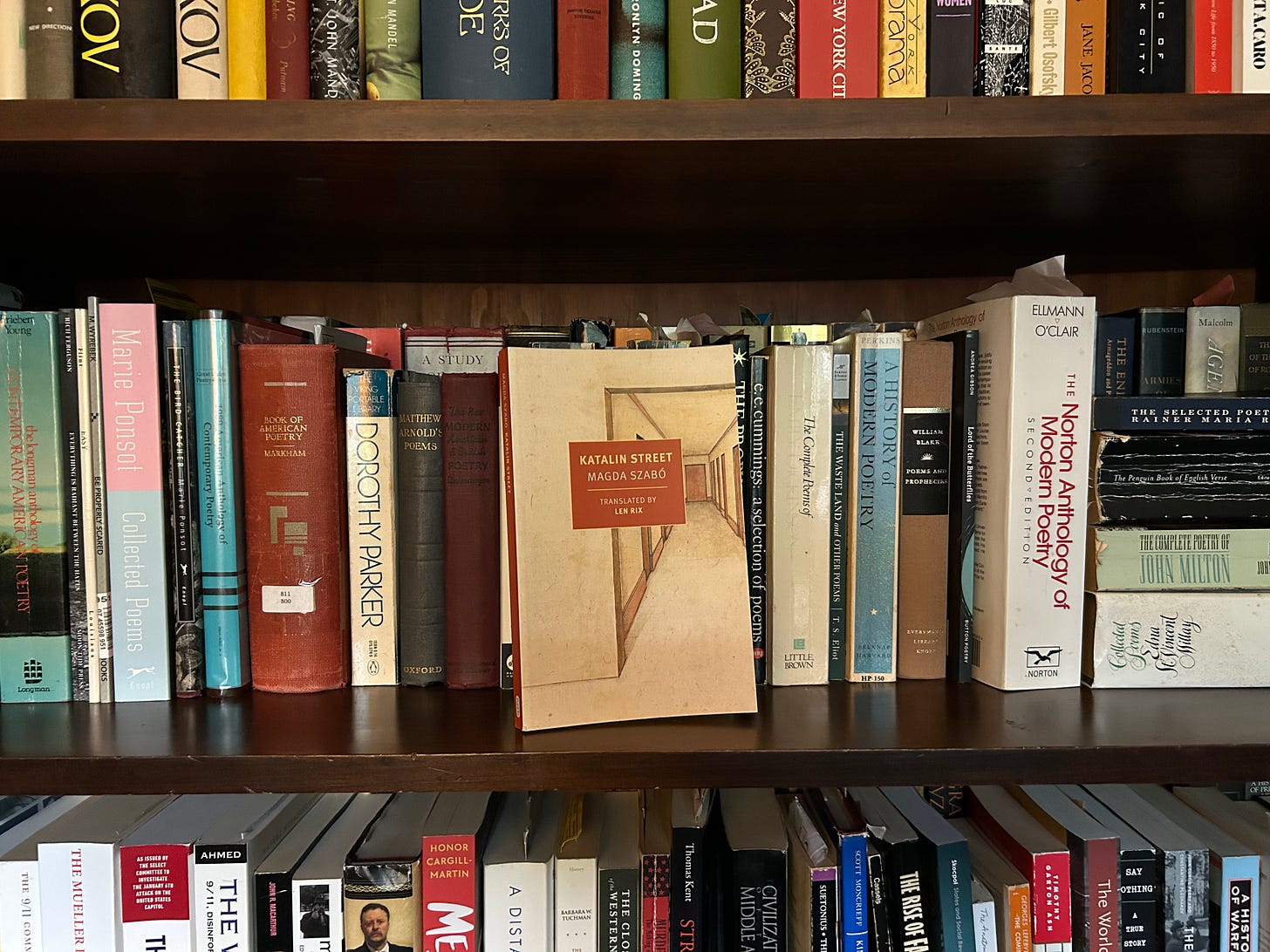

New York Review Books is a lovely little imprint that puts out novels translated to English from other languages. I am fond of the look and feel of the books, and I buy them whenever I see one at a book fair. In rearranging my bookshelves this past week—a relaxing bit of frivolity I granted myself as a reward for moving everything else around—I came across one of these novels: Katalin Street, by the late Magda Szabó, arguably Hungary’s greatest 20th century writer. It is a slender volume, Great Gatsby length, and it seemed to be calling out to me, as books sometimes will. So I opened it, and read the first three paragraphs. In Len Rex’s gorgeous translation, Szabó seemed to articulate, uncannily, the thoughts now forming in my own tired brain:

The process of growing old bears little resemblance to the way it is presented, either in novels or in works of medical science.

No work of literature, and no doctor, had prepared the former residents of Katalin Street for the fierce light that old age would bring to bear on the shadowy, barely sensed corridor down which they had walked in the earlier decades of their lives, or the way it would rearrange their memories and their fears, overturning their earlier moral judgments and system of values. They knew they should expect certain biological changes: that the body would set about its work of demolition with the same meticulous attention to detail that from the moment of conception it had applied to the task of preparing itself for the journey ahead. They had accepted that there would be alterations in their appearance and a weakening of the senses, along with changes in their tastes, their habits, and their needs; that they might fall prey to gluttony or lose all interest in food, become fear-ridden or hypersensitive and fractious. They had resigned themselves to the prospect of increasing difficulties with digestion and sleeping, things they had taken for granted when young, like life itself. But no one had told them that the most frightening thing of all about the loss of youth is not what is taken away but what is granted in exchange. Not wisdom. Not serenity. Not sound judgment or tranquility. Only the awareness of universal disintegration.

They came to the realization that advancing age had taken the past, which in childhood and early maturity had seemed to them so firmly rounded off and neatly parceled, and ripped it open. Everything that had happened was still there, right up to the present, but now suddenly different. Time had shrunk to specific moments, important events to single episodes, familiar places to the mere backdrop to individual scenes, so that, in the end, they understood that of everything that had made up their lives thus far only one or two places, and a handful of moments, really mattered. Everything else was just so much wadding around their fragile existences, wood shavings stuffed into a trunk to protect the contents on the long journey to come.

At first blush, “awareness of universal disintegration” seems so bleak, so glass-half-empty-and-leaking-from-the-bottom. But, I mean, we must reckon with our own mortality—with the darkness building outside the door. Because everything disintegrates. Even mountain ranges wear down over time! And awareness, and then acceptance, of universal disintegration is essential to not living in fear.

As to the memory-parcel Szabó speaks of: yes, the contents may have shifted during packing. Yes, the customs office of our mind may have torn open the packages for inspection. But if a Hungarian novelist could make these observations in 1969, when whatever combination of soul matter and stardust that would form me was still unassembled in the void, then this inkling I’ve been having lately must be universal, or universal enough that it’s nothing for me to worry about. As C.S. Lewis said, “We read to know we are not alone.”

Twenty-five years is a long time. Light can be touched. Darkness can be scary but it is not inherently bad, any more than heaviness is bad, or solemnity. (Gravity can mean either heaviness or solemnity.) Nirvana is typically thought of as the Eastern equivalent of the Christian concept of Heaven, but as I learned in the Introduction to Buddhism class I took when I was the same age as my kids are now—or, at least, what I remember from that class—nirvana is Sanskrit for extinction. Nirvana is what is achieved when we evolve enough to stop the cycle of reincarnation. Enlightenment, paradoxically, consists of accepting the darkness.

And as if to prove that it still has plenty left in the tank, my brain has just now supplied me with a quote to conclude today’s piece—an exchange between the nerdy Anthony Michael Hall and Judd Nelson’s rebellious cut-up in The Breakfast Club. The former is explaining to the latter his F in shop class:

—Without trigonometry, there would be no engineering.

—Without lamps, there would be no light.

Shine on.

Photo credit: Yours truly. Some of my freshly rearranged bookshelves.

Oh Greg, I understand the excited and exhausting turmoil of sending your two kids off to college. Mine were 3 grades apart, but both were gut-wrenching. Just remember they will come back many times.

On getting old- I am almost 69 and it is not fun. Physically things start to hurt, in my case I can’t do 1/2 the stuff I used to. And the mind, like you described, is another story. Fogginess of thinking, decision making, old memories replacing current happenings. Maybe it’s the way our mind prepares us for more and more losses in this life.

Thank you for your beautiful essay, and for introducing me to “Katalin Street”.

Things will be okay, just different.

Some of my favorite quotes on life passing

There's a point in which life stops giving you things and starts to take them away.

Many of our deepest motives come not from adult logic of how things work in the world, but out of something that is frozen from childhood.

Ernest Becker wrote in The Denial of Death: “To live fully is to live with an awareness of the rumble of terror that underlies everything.”

“I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief… For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.” – Wendell Berry

Historian Will Durant possibly said it the best: “The past is not dead. Indeed, it is often not even past.”

Life swirls by like a drunken wildfire

Unknown