Dear Reader,

Today is Father’s Day—my 51st Father’s Day as a son, my nineteenth as a father, but my first since my father died. I’m not a big fan of these Hallmark holidays. I don’t think my dad was, either. Father’s Day, coming as it does a month after Mother’s Day, always smacked of a sequel that wasn’t quite as good as the original, a hasty enterprise designed to further cash in on a potentially lucrative franchise, the Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom of calendar observations. Furthermore, I’m not sure the literal patriarchy needs yet another feast day. With that said, screw it, I’m a dad, bring me a Rolling Rock and let the cornhole games begin!

Today also marks the 24th Father’s Day that I have been a son-in-law. I’m very fortunate to have a great relationship with my father-in-law. Not everyone is so lucky. Mine is named Franklin St. John. He’s a sweet guy, generous and kind. I enjoy listening to his stories, as he’s led a remarkable and interesting life, populated by colorful characters with delightful names. (I purloined the surname of one of his old flames and gave it to one of the villains in my first novel, Totally Killer.) Two years ago—or was it three? Since the pandemic, I’ve lost track of any ability to mark time—we decided to work on a book about that life. I’m pleased today to bring the fruit of that labor to you, Dear Reader.

For those of you who are curious to read something of mine that’s more longform, but have somehow resisted the urge to tackle a 700-page historical novel about the Byzantine Empire, Success Stories of a Failure Analyst might be just the thing. It’s a slender volume, rich in personal detail, and, best of all, it has nothing whatsoever to do with the twice-indicted FPOTUS. I’m sharing the preface to the book, below the jump, for the Father’s Day edition of “Sunday Pages.”

Happy Father’s Day to all the dads out there. May your hot dogs and hamburgers be grilled to perfection.

And happy Father’s Day, Dad, wherever you are.

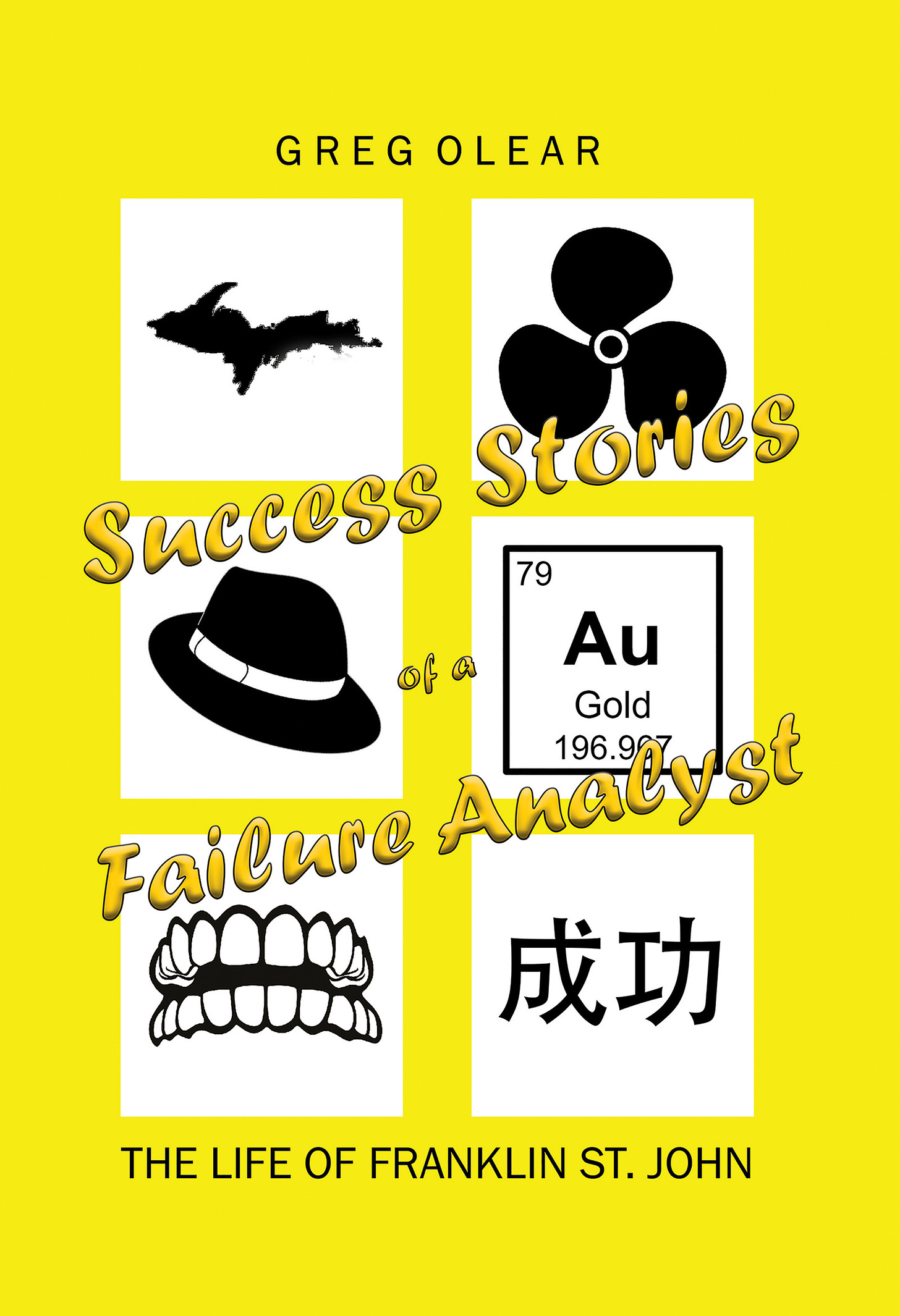

Success Stories of a Failure Analyst:

The Life of Franklin St. John

Preface

My father-in-law was born in 1938, in a house without a toilet, in a flyspeck of a town in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. His grandfathers were both lumberjacks. His father was a plowman. If anything was expected of Franklin St. John at all, it was that he would follow one of those two career paths. Instead, through more quirks of fate that can quickly be recounted, he became, of all things, a metallurgical engineer.

In his colorful early career—colorful for an engineer, that is—he encountered repatriated Nazi scientists, crooked cops on the make, and mobbed-up steel plant managers. At the height of the Vietnam War, he worked for a company that made engines and propellers for army helicopters. As a failure analyst—an industrial job that kept him far away from the jungles of Indochina—Frank identified and fixed a manufacturing problem that had led to helicopter engines failing on the battlefield, saving the lives of untold number of soldiers.

When he was 40 years old, he invented an alloy called “unit bond,” specially engineered to adhere to porcelain—most metals don’t—and intended to be used as a substitute for gold in the manufacture of dental bridges and crowns. Unit bond cost 40 cents an ounce to make. He sold it for $16.95 per ounce. Customers ordered hundreds of ounces at a time. When he cashed out ten years later, Frank was worth something like $18 million—and he was still bringing home $300,000 a year, guaranteed, as part of his buyout agreement.

He gave away the lion’s share of his fortune, mostly to his alma mater, Michigan Tech. It is no stretch to say that he has helped thousands of students pay for their schooling. (“Schooling” is a word he uses a lot). He retired at age 50, traveled the world from Hong Kong to Vatican City to Antarctica, and became obsessed with the UConn Women’s basketball team.

Through it all, Frank seemed always to know when to stay and when to leave. At all times, he seemed to have, as he put it, a “sixth sense” about how to handle certain situations and what to do next—almost like his guardian angel was top of its class.

Although wealthy, Frank is not extravagant. He drives a Lexus, but he lives in the same Cape Cod house in the same middle-class Connecticut town where my wife grew up. When I first visited him there 22 years ago, he was sitting in a den built out of the breezeway between the garage and the house proper, bundled in blankets because there was no heat in there, watching the UConn game on a crappy console TV. But he does enjoy the ancillary benefits that his wealth confers. He likes to overtip. He likes to randomly buy his loved ones gifts. After his father died, he flew back to the Upper Peninsula and, in 24 hours, negotiated and closed on a new lot for his mother to build a house; he paid cash. He once put ten grand in a shoebox and mailed it to his sister in Michigan.

Franklin is a storyteller, like his father and grandfather before him. Over the last few years, he wrote down a lot of his stories, recalled in a folksy and endearing style. These memoirs run to 100,000 words. But how to present them as a coherent work? Would anyone outside his immediate family be interested in sifting through the anecdotes?

He asked me to help him with this. To ghostwrite, maybe. The original idea was to focus on his time at the steel plant, when he encountered such corruption that a contract was put out on his life, and he had to worry about tons of rolled-up metal “accidentally” dropping on him. But after interviewing him at length, I decided that limiting the book to that one period of time was a disservice to the rest of his story. The tales of his childhood, in that flyspeck town on Lake Superior, were so fascinating, so rich in detail, that they simply could not be discarded. Also, Frank’s memoirs are exactly that—memories. He isn’t one to look for larger themes, or even second-guess his actions, beyond an occasional, “Oh, I shouldn’t have done that.” He was a failure analyst by trade, but that doesn’t mean he’s inclined to analyze his own failures. He will acknowledge mistakes, of course, and he readily and almost proudly admits that he’s failed much more than he’s succeeded. But what he sees as a personal account of random events that happened to him, I view as a story of 20th century America itself.

Franklin St. John is a legitimate rags-to-riches tale, a Horatio Alger story—the sort of character who isn’t much seen outside of fiction. He’s the American Dream made flesh, a popular myth come to life.

“You’re that rarest of things,” I told him. “Something people talk about all the time, but hardly ever encounter: A self-made millionaire.”

He looked at me with his mouth slightly open, an expression he often makes—and has always made, as evidenced by the sole baby picture that exists of him—when he is deep in thought. “I never thought about it that way,” he said.

And there was the problem in a nutshell: Frank did not have the requisite distance from his subject to understand how much in his biography was literary. This literary quality is what I wanted to bring out, but I couldn’t effectively do that while pretending to be him, as the ghostwriter must.

So we decided that I would write the book, from my point of view, and I would do my best to be critical, objective. A good biography is an examination of a life, after all, not just a simple chronicle of events.

“Maybe it will be a best-seller,” he said, and I could see the familiar fire in his eyes. As an engineer, Frank favors quantifiable results: 4.0 grade-point averages, net profits, free throw percentage, NCAA Women’s Basketball Championship trophies, and so on. He tends to view success in these terms, too—much to the consternation of my wife, who as an artist is more about the shades of gray.

“Maybe,” I said, hedging, “although, I mean, that’s beyond my control.” I try to temper his expectations. After all, the odds of a book like this one winding up on a best-seller list are as long as…well, as the son of a plowman from the Upper Peninsula making multiple millions in metallurgy. Once you’ve achieved that sort of success, you must feel like everything else you try will succeed just as spectacularly.

And who am I to tell him otherwise?

ICYMI

Victor Shi returned to The Five 8 on Friday, giving us a much-needed infusion of hope. Please note that we will likely be dark this coming Friday.

A really cool guy... interesting stories..My pops was a Oner too.Seems like we don't have many anymore.Of course 2 weeks ago I bestowed that honor on yourself( time is fuzzy in my mind too after COVID .. however My pops was a self made millionaire in the medical field,but gave his discoveries to the public without patent.He was so happy to not be the 6ft tall 135lb skeleton he was during the Depression.In fact he and his other doc pals bought hundreds of ocean front property in the keys..did Enviro Impact Studies,and hoped to build a golf resort.G.Boosh and cronies ripped it out of their hands 20 years later,when Papa was disabled by heart disease. Billions were now not to be had.He gave so much to America, worked on Polio Vaccine with Salk.Set up Mash units in the Army.But vile GOP (fascists)had to take that from him.His land bordered Boosh's Yacht resort,so Papa took what he spent as payment,and 20 years taxes not reimbursed.That is Florida,That is America.No plaques,no Honors just grand theft by the Greedy.So America always Maximize your Profits, because in America.. Profits are EVERYTHING.

Sounds like a wonderful read, and man. Sounds like much more than his guardian angel at the head of the class. Personification of the American Dream. Thank you…